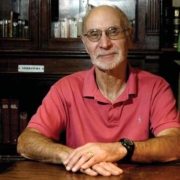

Daniel Friedrich

Dissertations and the Field of Education

Today we look at the way in which dissertations in the early 20th Century produced and governed the emerging field of education and how these new knowledges moved across the world. Our focus is on Teachers College, Colombia University.

My guest is Daniel Friedrich, an Associate Professor of Curriculum and Director of the Doctoral Program in the Department of Curriculum and Teaching at Teachers College, Columbia University. Together with Nancy Bradt, he recently published in the latest issues of Comparative Education Review “The Dissertation and the Archive: Governing a field through the production of a genre.”

Citation: Friedrich, Daniel, interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 245, podcast audio, July 5, 2021. https://freshedpodcast.com/friedrich/

Will Brehm 0:26

Dani Friedrich, welcome back to FreshEd.

Dani Friedrich 1:18

Thanks, Will. It’s always a pleasure to talk to you.

Will Brehm 1:20

So, can you tell me a little bit about the type and sort of influence that Teacher’s College, which is now located at Columbia University, has had on the field of education specifically?

Dani Friedrich 1:31

Yes. So, when you hear names like Maxine Greene, Isaac Kandel, Edmund Gordon, John Dewey, those are names deeply associated with Teachers College. So, when you think of the history of education in the US but also abroad, it’s really hard not to see the huge influence that TC has had in the field of education writ large, right? Also, it’s important to consider that during the first half of the 20th century, most of it, TC had the largest doctoral program in the nation. And so, all those names I mentioned, all of them had many, many students that brought those ideas to different places. And it’s not any students that came here, right? So, if you think about Teachers College, and Columbia University, we’re talking about ultra-elite students from around the world. So, also people that already were well-positioned in their countries to come to New York City, to come to Columbia University, were really at the top of our societies in terms of having access to resources, having networks, speaking the language in many cases. And so, all of those people that came from different places of the world to TC, then many of them went back to their countries and were key players in setting up institutions, systems, models of education. And this all plays into how this paper came to be, which has to do a bit more of my personal experience, which was that I was department chair for curriculum and teaching for two years, a couple years back. And as the department chair, I was impressed with the amount of people from different places of the world that came to see me, set up appointments, and tell me how -say for example, a Chilean person that came and said, “Well, the person that founded early childhood education in Chile, Irma Salas, was a doctoral student of TC. So, I’m here really to look at the archive. And the founder of my university in China studied with Dewey here in TC so I’m here to look at archives”. So, as department chair, I really had first-hand experience with how many people came and had connections to TC. So, I was fascinated by that and that’s what led us to think about the role of TC in the field of education.

Will Brehm 3:43

It’s quite fascinating to think that there were so many international students in the early 1900’s studying at Teachers College, and then going back to their countries or going back to the different institutions where they came from, and sort of impacting them, changing them and using the ideas they might have learned at Teachers College to do so. Do you know how many international students? In a typical cohort, was it 10%, or how big of a population was it?

Dani Friedrich 4:15

So, to get at that information, it was not easy, right? So, Nancy and I, what we did initially -and another group of students helped us also create this initial archive, Kara Gavin and Ana Paula Marques de Carvalho, who was a doctoral student from Brazil visiting TC a few years back. And so, what we did is first we found out that Teachers College has terrible archives unfortunately. There’s a lot of stories about what happened to those archives and we can talk about them. But so, we went to Columbia University and looked at the commencement program. And student commencement programs where they had listed the undergraduate institution that students had attended and their degree. We sorted out the education students and we used first as a proxy for the first list of international students where their undergrad was abroad. Then we also Googled all the names, and we looked at different sources to get all the names. And so initially -the paper that we’re talking about is only part of the project. The paper is from 1900 to 1920 but our project went all the way to 1940. So, between 1900 and 1940, we read 110 dissertations produced by international students at TC. In the first two decades, the ones that are for this paper, we used 20 dissertations out of the 21 that were produced. Only one was not available to us from a South African student. There’s only one copy of the dissertation alive and it’s in a library in South Africa and we just couldn’t get access to it but all the others we got. So, for the time, it was a significant number. As I mentioned before, it was not only the largest doctoral program in education but it’s also the one with the largest amount of international students.

Will Brehm 5:49

That’s quite interesting. And so, what did you expect to find by looking at dissertations when it comes to trying to unpack some of the influence TC has had?

Dani Friedrich 5:59

So, a dissertation in a way, is defined by the idea that it’s supposed to present new knowledge, right? So, when you think of master’s theses, or integrative projects, usually there are different kinds of work. Sometimes they’re syntheses, sometimes they are practical projects or curriculum designs, but a dissertation is supposed to present new knowledge, at least that’s how we think of it now. But the way we conceptualize it in the paper is of a genre that is as a discursive practice with rules that have a history that set up what is allowed to be said, how is it allowed to be said, how is it to be counted as new knowledge? So, when we looked at the dissertations, our idea was, first of all to focus on international students because we want to see the relation between TC and the world. And we focus only on dissertations and not master’s project. First of all, because master’s projects would have been almost an infinite archive, right? It’s many, many more students. But also because of this goal of creating new knowledge. So, the idea was, how are the ideas that are being produced at TC, are circulating through the faculty to the scholars have a huge influence in the US? How are the ideas traveling? How are they being made sense of by the students that come in with different frameworks from their different countries? And in the future to think about also what happens to the knowledge when it lands in other places?

Will Brehm 7:18

And so, you ended up looking at around 20 dissertations for this paper, and you ended up coming up with different ways of categorizing these dissertations. So, the first type that you’ve identified -and I guess I should say that you also recognize that the boundaries between these types are a bit blurred, and it’s not so distinct. But the first type you come up with is called the “encyclopedic dissertation”. What do you mean by this?

Dani Friedrich 7:46

So, before we get into that, it is important to know that we are very aware of the act of categorizing is in itself, a colonizing effort, right? Sort of, we’re trying to dominate knowledge that is much more wild and we continuously struggle with the idea of an unruly archive. And our efforts to sometimes organize it in order to produce a heuristic but at the same time respect that unruliness, right? Because much of our work is framed as -and here, we draw a lot from Keita Takayama’s work and his call to dig into the cultural entanglements of the field, right. And so, we try to understand how dissertations are also tools for colonizing projects. So, I just want to mention that because we can talk about these three categories, which I think are really interesting in a way of reading dissertations but also to understand that that’s our own effort to produce an order out of a much more chaotic archive. So, the encyclopedic dissertation is the one that seeks to be an authoritative voice, presenting the building blocks of a universal encyclopedia to an unknowing audience. So, they tend to present topics like education in Mexico, education in India, or not only located in places, but also thinkers. Sort of the idea of Greek moral education, or Herbart’s thought. And so, we call them encyclopedic because they present themselves as all-knowing on that specific topic. And they don’t engage in arguments with other authors because what they present is the one objective view of that thing. At least that’s how, in some ways, they present themselves. As I said, it’s unruly so you can see tensions within dissertations that struggle against this idea of them being objective, for example.

Will Brehm 9:32

Do you have an example of that?

Dani Friedrich 9:34

Yes, I think maybe one of the most interesting examples here is Manuel Barranco’s dissertation. He was a Mexican doctoral student who produced his dissertation around education in Mexico. And basically, what he does is he enumerates all the races in Mexico, enumerates the history of the different periods of education in Mexico, but in different parts, what he’s trying to say just by why is he doing, right? And it’s interesting because what Barranco says is that most Mexicans know of the US only the warships that landed their ports and bombed them. And he wants Mexicans to know the other Americans. The ones that build schools and bring progress to the world. And so, he wants to approach, what he calls, the Indians to lift them out of their lack of culture and civilize them but not as colonizers but as friends. He uses those kind of words. So, you can see in Barranco his own struggle with presenting a solid building block on the encyclopedia. But at the same time, him being unable to remove himself from the purpose of the dissertation which is really to introduce to the American people the fact that the Mexican people have their own culture, have their own struggles, and to introduce to the Mexican people an idea of America as a friend. And so, it’s really interesting, the way in which that dissertation presents this on the one hand, encyclopedic knowledge of Mexico, but, on the other, the struggles of the author as what is his role there in bringing ideas to whom.

Will Brehm 11:07

Right. And it sounds like it’s a struggle between his expected role by perhaps fellow TC students and professors about taking the ideas back to Mexico, but then his sort of expected role as being a Mexican national, and trying to educate the Americans on all of the different aspects and qualities of the Mexican context and culture that perhaps are often missed.

Dani Friedrich 11:33

Exactly. And so, for example, one of the things you see in his dissertation is an enumeration of races. This is clearly a way of reading race from US/European perspective of the time in his strict category. But that process already is a flawed process. Not only because of the assumptions of it, but by the idea that he can encompass all the population. And Barranco himself struggles with that, with having to use these tools to fit them into the Mexican setting. So, it’s really interesting to see his own positionality being caught in this on the one hand, European colonial project of a dissertation, but also his own awareness of the dissertation as a political project of peace between US and Mexico.

Will Brehm 12:18

So, do you think his dissertation was an outlier in this sort of category of encyclopedic dissertation where the tension is so, in a sense, palpable between these two different sides of the author? Or is that an outlier, and it’s more common to just see dissertations that are, you know, here’s the truth of this context?

Dani Friedrich 12:38

It’s definitely more common to see, what you said, this is the absolute truth, objective truth and there’s no discussion. But the first dissertation in our archive, chronologically, from Chamberlain from 1900. The first dissertation to be defended at Teachers College, was about education in India. And Chamberlain as himself, a man of British ancestry in India, talks about the British Empire, disrupting Indian education and tradition in a way that’s fairly critical to the British project without giving up on the idea of British as a civilizing force. So, Barranco and Chamberlain are not the majority, but they’re also part of the struggles of the field from the beginning.

Will Brehm 13:19

It’s interesting to recognize that struggle from the beginning because I feel like that happens today. I have students who come from different countries and you can see them struggling with trying to sort of represent that country and take ideas back to that country, but also sort of educate me about their country in ways that I might never have known previously. So, in a way, I feel like that tension is so contemporary.

Dani Friedrich 13:46

That is the tension I live with every day, right? So, I came from Argentina to the US. In Argentina, in the circles I move, the US is the Empire. The US is the thing you fight against in many ways, right? And so, my own history is marked by that tension by the fact that when I go back to Argentina to present some of my work, I’m read with a lot of skepticism as someone coming from the US, right? But at the same time, I’m someone coming from the US with the knowledge and experience having lived in Argentina up to my mid-20s. So, when I read Barranco’s dissertation, for example, I read many of my own struggles – of course, 120 years later.

Will Brehm 14:25

That’s quite amazing to realize that 120 years later there’s still a lot of ideas that resonate. I mean, I’m sure there’s so many people in our field that have similar experiences. So, let’s move on to the second type of dissertation that you’ve identified with all the caveats that you’ve given earlier. You call it the comparative dissertation. So, what are these types -I mean, it sounds obvious, comparative- but how do they govern knowledge and subjects and relationships, thinking more about the discourse that you were really trying to uncover?

Dani Friedrich 14:58

So, the comparative dissertation does not attempt to present a totality but it attempts to isolate specific phenomena in different settings to then compare them to each other, or compare them to a norm. And in order to do that the authors have to establish their own authority to do that, to isolate, but also to provide the tools to measure and compare. This is where we tend to see the pre-history of the field of comparative international education, right? There’s a lot of writing from Erwin Epstein, from Liping Bu about the role of Teachers College in founding the field of comparative and international education, usually starting around the 1920s with the foundation of the International Institute. This is sort of the pre-history of that. It is a moment in which in education, there’s not subfields yet. It’s all, because it’s a small program, you see the same faculty participating in all the committees and ideas being shared more widely. And so, in the comparative dissertation, what you see is these comparisons starting to understand the field of education as a field that can be used to compare systems, models, ideas, and how they flow in different places. One, I think, wonderful example that was also explored in a dissertation produced by [Flash?] in the mid-90s, was about Charles Loram. Charles Loram was a South African white man that came to Teachers College to study how the US, in the first quarter of the 20th century, how the US educated Black people in the south to understand how the US dealt with, quote, unquote, the inferior populations, right. And so, he learned that about the US in the south and brought those ideas to South Africa to basically help found the apartheid system in education. And that’s a fascinating dissertation because on the one hand, Loram takes tools from Thorndike in measuring intelligence and tests, he takes things from school administrators to understand how to administer a system that tries to help teach manual labor. But also, this is really interesting to us, is that the third signature in Loram’s dissertation, which is explicitly erased is John Dewey. John Dewey is part of Loram’s committee. And it’s really interesting to understand, again, this entanglement, this deep complex relation between coloniality, the role of TC, the role of the US and how ideas flow exactly.

Will Brehm 17:31

-and how these ideas then sort of get implemented inside institutions, right? Justify particular practices, as you’re saying, in South Africa. I mean, that’s really quite an amazing -it’s a story that I’ve never heard before about how at Teachers College, there was a student who learned all about how African Americans were being educated in the South and used that knowledge to then institute apartheid.

Dani Friedrich 17:57

Right. And he was part of, again, what Fleisch calls, the “South Africa Club”, which is a group of five people that came in the first three or four decades of the 20th century to TC. They were all connected to one another. And he was part of a project, right. But it’s fascinating to see that and to see also the emergence of a particular kind of expert. We’re seeing that not only a particular kind of knowledge is being produced but particular ways of knowing. And the expert, that is, I think, is the genealogy of what we now see as the consultant, right, the international consultant. The one that knows what to look at, how to look at different things in different places without paying much attention to context, in order to then take those lessons and apply them somewhere else. That’s what you see in these dissertations. These scholars are trying to justify the ways in which you can look at education of African Americans in the South and then think that that is applicable to South Africa.

Will Brehm 18:51

Right. It is an interesting issue of the educational expert and how comparison becomes a tool that sort of legitimizes and gives power to that expert. The ability to quote unquote, compare is a very powerful tool to wield. So, the third type of dissertation that you look at is what you call the psychometric dissertation. What are these types of dissertations?

Dani Friedrich 19:18

So, this is, in some ways, a little different. Whereas the first two types are messier, they really mix with one another. They were hard to create different categories. The psychometric dissertation looks and feels different. These are dissertations that treat education as an experimental science following a clearly positivist paradigm. They are, like I said, more homogeneous, and mostly they describe experiments and results without much framing. They share with the encyclopedic dissertation the idea of cumulative knowledge. They build on one another in order to build this full understanding of the human mind. And they share with the comparative dissertation the importance of comparison and setting up norms and standards. But however, the production of expertise is very different. This is about objective followers of specific methodologies that lead to the verification of reproducibility in the experiments. So, most of our article, it sort of tries to avoid looking at the biographies and the names of people in order to focus mostly on the text. But in this category, it’s really hard to avoid the outsized role of Edward Thorndike. Thorndike sponsors all dissertations in this category. And you can see his imprint on the idea of what counts is what can be measured, what can be measured is knowledge and what cannot be measured is not knowledge. Also, you can see he’s eugenic ideas really at play in comparing the intelligence of different races, comparing the intelligence of different populations, and using those experimental methods to inform pedagogy, to inform school administration, to inform the field writ large.

Will Brehm 21:08

Who was Thorndike? Can you give a quick overview of who he was and why he might have such ideas?

Dani Friedrich 21:13

So, Edward Thorndike, was hailed by some folks as one of the founding fathers of experimental psychology and education psychology. He was really a man obsessed with measurements, with IQ. He drew some of the tools for measuring IQ, and then used them to engaging in conversations with people like in what we now would call subfields. But at the time really in a small department were colleagues. One small tidbit is that Teachers College until last year, had one of its buildings named after him. And through activism of students and faculty, the board finally voted to rename that building because it’s really hard to look at Thorndike and to look at his contributions, without considering the role of eugenics in his ideas and how again, they travel. If we go back to Loram, Loram drew a lot from Thorndike’s ideas about the difference in intelligence among races in order to bring this idea to South Africa.

Will Brehm 22:23

Interesting. So, these sort of experimental methods, were these sort of new in the early 1900s? Were they becoming popularized at that point?

Dani Friedrich 22:34

So, they were new for education, right? The field of psychology was in the process of being established as an experimental science, but the idea of applying this to education was really starting to emerge. And that’s why Thorndike has such an outsized role. I think that it’s also telling about the relationship between Teachers College and Columbia. And Teachers College never being taken that seriously by Columbia because education was not seen as a serious science or a field of research. And Thorndike really trying to prove to Columbia and to psychologists that you can treat education as a hard science. That is what is relatively new at the time.

Will Brehm 23:19

Hmm, that’s quite an interesting insight. Do you see any connections to some of these experimental methods, this psychometric dissertation, do you see any connections to today? Are there legacies of this type of work still in education?

Dani Friedrich 23:36

Going back to the struggle to rename that building, there was, I have to say, quite a bit of resistance from psychologists who still see their work as indebted to Thorndike’s ideas. So, whereas while I’m not a psychologist, myself, and I cannot claim that expertise, experimental psychology, and part of the ways in which the neurosciences are trying to have an impact on curriculum, on pedagogy, on school organization, I think you can draw certain lines between what Thorndike’s trying to do, and the idea that if only we knew more about the brain, we would be able to solve the problems of education. I think there is something to be said about that connection, right? It’s not linear. So, when I say draw a line, it’s not linear, there’s a lot of discontinuities. And within neurosciences, there are a lot of people that have much more nuanced views. But when we see, for example, the ways in which some of the insights from the neurosciences are boiled down to silver bullets – not necessarily by neuroscientists, but by people that try to do that translation and bring those insights to education – I think we can see a lot of Thorndike’s legacy there.

Will Brehm 24:47

Yeah, I mean, I guess this idea of scientific rationality is certainly still with us in some parts of academia.

Dani Friedrich 24:55

Definitely.

Will Brehm 24:56

So, when you look across this messy archive that you’ve begun to unpack here, what sort of rules and norms do you see governing this genre of the dissertation and its production of knowledge.

Dani Friedrich 25:15

I think maybe one of the most fascinating thing of reading dissertations at a time in which it was not taken for granted that education was a field of research. When it was not taken for granted that you could have a doctorate in education. It is one of the first ever doctorates in education. So, one of the most interesting things here is that the rules are in the making. So, it’s really hard to figure out rules because the genres have histories. And by that, what I mean is they have changed, and they have moments in which they start to coalesce. But the earlier dissertations are truly hard to – some of them, you read them and you don’t recognize it as a dissertation. There is a dissertation, for example, that is basically a list of all the ways in which you can measure school efficiency without any framing, without any conclusions, just a pure list of measurements. That includes, for example, and I’m not paraphrasing here, how much toilet paper a school uses, how much chalk a school uses, the height of the chalkboard. So, it’s just a list of things you can measure in school, and that is the whole dissertation.

Will Brehm 26:18

And that got someone a PhD?

Dani Friedrich 26:20

Exactly, right? And so, it’s really interesting to think that – I mean, now, of course, that would never fly. But that tells you that what we now take for granted as what constitutes a dissertation has a history like that of any genre. And so, we need to understand that because it has a history, it could be different. What we assume now to be the absolute must of a dissertation, is not necessarily so, or it’s a historical construction of how we see what counts as knowledge, whose knowledge counts, which ways of knowing counts within academia. So, looking at the archive of dissertations, for me, it was not that much about seeing which rules govern them but how are the rules that govern us now produced at a time when it was not clear that these could have rules?

Will Brehm 27:05

Right, right. So, in a sense, do you think you are more aware of the rules that govern dissertations today? And is that changing your practice for supervision of PhD and even master students?

Dani Friedrich 27:20

I think so. I mean, it’s hard to say my own practice can be completely different from the whole field, right? I don’t want a student to produce a dissertation that I like but then it’s not recognized as a dissertation in the field writ large and the student then can’t get a job. But also, I start to question, what is it that we take for granted. For example, the ways in which we force students to put markers or like tribal belonging in their dissertations. Who to quote so that people can plant their flags as this person belongs to my field, to my tribe, to my group? And how is it that we came to think of that as part of the dissertation? How is it that we came to think that a dissertation has to have several number of chapters? The first chapter is theoretical framework, second lit review, the third is method. Why is it that we are forcing different ways of knowing, different ways of reading the world into this very rigid structures? And clearly, other people are doing this. TC, I think, among many other institutions has a lot of space for creativity if you push for it. A few years ago, we had a graphic novel defended as a dissertation, and different ways of using narrative knowing as dissertations. But the archive shows us that there is a world of possibility out there if we try to think about how is it that just forcing ways of knowing into particular format is also, once again, a colonizing project. If we want to decolonize our field, we need to think about the forms and the ways of knowing that are validated within academia. And one more thing I would like to mention is that for us, and this is for everyone else, we presented an initial draft of ideas of this paper at CIES in 2019 and the feedback we got from our discussant and from the audience deeply informed the final shape of this paper. So, I want to just highlight the collective work of producing these papers that are not just all the authors, but the conversations we have in places like CIES.

Will Brehm 29:16

It’s just a really interesting entry point to think about decolonizing our field, to think about our practices with dissertation supervisions, to think about what knowledge is. So, I’m really looking forward to your other publications that are going to bring us up to the 1940s on this project. And I can also see this project continuing to this very day because we continue to build this archive of dissertations. So, thanks again for joining FreshEd.

Dani Friedrich 29:42

Thank you, Will. It was my pleasure talking to you.

Want to help translate this show? Please contact info@freshedpodcast.com

Related Guest Publications/Projects

The dissertation and the archive: Governing a field through the production of a genre

Mentioned

Manuel Barranco’s dissertation

William Chamberlain’s dissertation

Erwin Epstein – North American Scholars of Comparative Education

Liping Bu – Educational Exchange and cultural diplomacy in the Cold War

TC Dissertation Archives (pre-1910)

Related Resources

Charles T. Loram and an American model for African education in South Africa

Beyond comforting histories: The colonial entanglements at Teachers College

Pioneering efforts of the International Institute of Teachers College, Columbia University

Educational Foundations and the Ed200f Course at Teachers College, Columbia University

The global politics for educational borrowing: Blazing a trail for policy and practice

Multimedia

Edmund Gordon on Head Start National Education Policy

Have any useful resources related to this show? Please send them to info@freshedpodcast.com