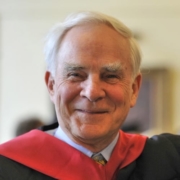

Elmi Slater and Pasi Sahlberg

Doing Things Differently in Education Research

Today we explore what it would mean to do things differently in education research. With me are Elmi Slater and Pasi Sahlberg.

Elmi Slater is a year 11 student from Canberra, Australia and Pasi Sahlberg is a professor of education at the University of Melbourne.

Today’s episode was recorded in front of a live audience at the University of Canberra.

Citation: Sahlberg, Pasi, Slater, Elmi interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 339, podcast audio, December 4, 2023. www.freshedpodcast.com/slater-sahlberg

Will Brehm 0:00

Elmi Slater, Pasi Sahlberg, welcome to FreshEd. Welcome to the University of Canberra. It’s so wonderful to have you here. Wonderful to have you in front of a live audience.

Elmi Slater 1:18

Yeah, thank you, Will. Happy to be here.

Pasi Sahlberg 1:20

Yeah, thanks, Will, it’s always a pleasure to join you and FreshEd [audience clapping].

Will Brehm 1:28

So, the conference, as we said over and over again, is “Change the World: Doing things differently in education research”. Now, at one point, it actually had a question mark at the end of that statement, “Doing things differently in education research?”. And I really liked the question mark. It sort of was a bit ambivalent, it was unsure; can we do things differently? Not a statement of fact. And I think that’s where we want to start today. Sort of thinking about what are some of the structures. What are some of the traditions that we have in the academic world -in the education space- that we might be rather trapped by? And one of the big ones -and this is perhaps a bit provocative. One of the big ones is education publishing. Last year, there was 2.8 million journal articles published. Four years earlier, there was 1.9 million. So, there’s an increase of journal articles, and for all sorts of reasons. And some subset of that is education related. And strangely, we have all this research coming out, more and more research coming out. And in the field of education, we have the same exact problems. There’s finance problems, there’s equity problems, there’s learning outcome problems. So, I guess, Pasi, to start; why is this the case? Why do we have more research and all the same problems?

Pasi Sahlberg 2:43

Yeah, thanks, Will. I think it’s a really important opening question here. I think one reason might be that we have had two or three years of COVID. And many of the scholars like myself, when you didn’t have time to do field research, or teaching or anything else, what did you do, you went to your desk and wrote journal articles, or books or something like that. So, there may be some reasons for that. But I would actually go a little bit further in your provocation, Will, and say that in education, we probably have about 300 or 400 education academic journals around the world. And we probably publish about, I don’t know, 25,000 articles a year, according to some data, about half of those 25,000 articles published every year in education have never been read by anybody else, except the referees, and maybe the author or co-author and their spouses or friends, okay. So, if this is true, then of course, it’s alarming. But even more alarming is that according to the similar sources, about 75% of all these journal articles in education have never been cited by anyone, which indicates that they have had no impact on anything. So, I think, you know, if you want to put it that way, then we really have to not only ask can we do things differently in education research, but we have to say that we must do things differently in education research. I don’t want to get into this space of doing a little mathematics and calculate how many hours of work or money has been spent on that work that nobody really reads? Or doesn’t have any impact on anything? And, you know, please don’t hear me as somebody who is against of publishing in journals, or writing. It’s quite the opposite. I’m a big fan of those things but just like you said, in your introduction, I think that if anybody is writing journal articles only because you think that I have to do that because of my next promotion, or this is the KPI of my faculty or university, I think we really need to sit down and ask is this really the smartest thing to do at all? And, you know, ask these questions that probably you’re going to be talking about here is that what would be the alternative ways of publishing? Making your research read more than it does now and have more impact. That people will get back to you saying that I read your piece, and it’s really interesting and important and we’re going to do something about it. Rather than continue to have this growing number of publications and books and other things that nobody reads. I think we have to be realistic and honest in front of these questions and in conferences and conversations like this really not only ask can we do things differently, but how we can do that so that we can get to a better space in publishing and making our voices heard.

Will Brehm 5:03

Really interesting sort of insight about trying to do things differently. And Elmi, I want to bring you in here because in a way, a lot of what we write about has to do with students like yourself. So, where do you learn about education and education research? Like, are you reading academic journal articles?

Elmi Slater 5:21

Unfortunately, I have to be part of the statistic that haven’t. But yeah, I don’t know. Through learning about education. I feel like there’s not much of a conversation among students or between students and teachers on how things are done. I feel like it’s very kept to the teachers and educators. I don’t know many students who have been involved in those conversations of making a change or education research.

Will Brehm 5:45

And what about education ideas. Ideas about how education happens, and where learning happens. Where do you find yourself learning about those things?

Elmi Slater 5:53

Well, I guess through having my mom as a lecturer for one in education. I’m grateful that I’m exposed to a lot of ideas that maybe I wouldn’t have considered otherwise. Recently, as of this year, I joined an indigenous culture and languages class, that Eli was talking about having taught me, and in that I think my interest in education was really cultivated because of how much I found, I enjoyed how that class was structured. And my results in that class, and my enjoyment, much higher than any of the other classes. And it really got me thinking about how we do things.

Will Brehm 6:32

And one of the things that happens in that class is about writing op-eds, is that right?

Elmi Slater 6:36

That’s in English. I was introduced to op eds through my last English assignment. Previously, in school, I feel like I’ve been so used to being taught how to write analytically. And through my secondary school experience, I was given the task of writing an op-ed, and I’d never even heard of that, even though I realized I knew what it was. But yeah, it had never come to me as a possibility that I could write one or that I would write one and get a grade for it because I was so used to writing analytically in a more formal way. And it was really interesting, breaking that down and actually having my own voice be a part of my writing process. And I feel like I had many opportunities through mostly writing analytically and formally in a more critical way. I haven’t had much of a chance to write something that’s opinion based but it still informs.

Will Brehm 7:27

And Pasi, you’ve done a lot of op-ed writing as well. Can you tell me a little bit about your experiences with op-eds?

Pasi Sahlberg 7:33

Yes, let me ask because we have a lot of experience here in the room; can I ask you to put your hand up if you feel comfortable explaining to a 10-year-old what an op-ed is. I can see two and a half hands. Okay, now I know the answer to the next question but I’m going to ask it anyway; put your hand up if you feel comfortable writing an op-ed, that you know how to do that? So, two or three. Actually, more people know how to do that than are able to explain to a 10-year-old what it is, which is kind of interesting. I mean, but this is not a surprising thing. You ask about my experience, Will, and I happened to have this rare opportunity to teach and do research for three years at Harvard University recently before I came here in Australia. And one thing I did there in all of my courses -I was teaching three or four different courses. It’s a graduate school of education so there were masters’ students or doctoral students. In all of my courses, the requirement of passing the course minimum requirement was that you have to write an op-ed. If you wanted to get an A, at Harvard, in my course, you have to get your op-ed published somewhere, but you had to show me that it’s published somewhere on newspaper or online anywhere, but you need to. Otherwise, it doesn’t matter what you do in your course, you cannot get an A before you do that. I did it systematically in all of my courses. And so, I had, during my time there probably about 400 students or something like this all around the world, mostly from the United States. And if you know anything about a university like Harvard, it’s quite difficult to get in there. But one of the criteria to get accepted to Harvard is your ability to write. The key element of acceptance is how you write your own personal essay, your story, okay? So, all these people are good writers of something. But of these 400 people that I had, I probably had four or five, who knew how to write an op-ed. There were more people who said that I know how to do that, because they thought that this is part of the assessment, of course, but handful of people actually knew how to do that. Every one of them even those who I know how to do an op-ed, or I’ve been writing kind of an op-ed; 100% of them said it’s really hard to do it. And everybody said to me it’s much easier to write a 25-page essay as coursework and get it accepted and highly rated then write a 400-word op-ed of something that would be really seen well. So, my experience is this. And I continued the same thing in teaching at the UNSW in Sydney for four years and now at Melbourne. I have the same thing that you can’t pass my course without writing an op-ed and getting it published because I firmly believe that this is a skill that all the graduates need in their lives and all the graduates that I teach that I send to the world I see them as change makers, nothing else but change makers. The task is to change the world or change their communities or schools or something. I’m not interested in preparing people for doing the same things over and over again -I want to prepare changemakers. And that’s why I’m saying that the skill to understand what an opinion piece or op-ed is an ability to write powerfully so that it has an impact and do it fast so that you can do it like right away here is an essential skill. But again, let me say that I’m not saying that my students would not need to know how to write a journal article or coursework -of course they do. But we do know that that type of writing has less and less likelihood to have any impact in practice. We need to equip the students also with the skills of communication that will help them to be changemakers. So, that’s my experience. That many people want to do that, many young people feel that this is exactly what I want to do. And the best part of my student feedback everywhere at Harvard, and here in Australia has always been to say that now I know how to write something that people will read, and they will read it again, and they will come back and ask me to write more. And that is a skill that we need to have with the students. So, that that’s why I continue to do so as long as I have a kind of a privilege to teach students. So, that’s why it’s such an important part of it. Being an educator and change maker, whether you work in policy, or research, or in a classroom, this is a skill that everybody needs. I’m

Will Brehm 11:17

I want to put you on the spot Pasi.

Pasi Sahlberg 11:18

Please do.

Will Brehm 11:19

Can you explain what an op-ed is as if we are all 10-year-olds [audience laughter]?

Pasi Sahlberg 11:24

I didn’t put my hand up. It’s a great question. That’s how I always start my course teaching as well. I ask my students, so what is an op-ed? Most people don’t even know where the op-ed comes from. Do you know where it comes from? It comes from the newspaper industry a long time ago. So, it means opposite of the editorial. So, if you open the New York Times, for example, that’s where it comes from. So, you have an editorial here, that the editorial board or editors write about something happening. Then on the other side there, there’s often a piece invited from an expert. And that’s called op-ed. It’s also often used as an opinion piece. So, the most important thing that people need to know, especially students need to know that, when I’m asking you to write an op-ed, I’m not talking about just writing about your opinion, whatever you think. Because everybody knows, if you ever tried to write an opinion piece to any newspaper here in Australia, you claim, you argue something. The first question you get from the editor back is, where’s the evidence for this? How can you say something like this? So, you have to be able to say something that is backed by your own research or somebody else’s research or evidence. So, it’s just a different way of writing about the things that we all do in a shorter and kind of a more reader friendly way. So, for me, there are two different types of the op-eds. There are op-eds that kind of point to the problem, help people to understand what the problem is. For example, school refusal. The op-ed could be what is it? And why is it a problem? Then there’s another type of op-ed that look at the solutions. Like why kids don’t want to go to school, here are my three proposals on how to solve the issue. The mistake that my students, almost all of them do, is that they try to do this both. You have 400 words to do that, and you just can’t get it. So, you cannot help people to understand what the problem is, let alone that you would help them to understand what to do with that. So, that’s why we need to be very careful when we are teaching people how to write op-eds, that you understand what it is and what you can do about it. But it’s a great opening question is, what are we actually talking about? And so often here in Australia, and Finland, and the United States, I’ve been in conversations where prominent academics say that we are not in the business of writing about our opinions that we are in a serious business of writing the truth and the facts. But then that only shows that we have a different understanding about what the op-ed or opinion piece is all about. So, it’s a critically important question to go through.

Will Brehm 13:39

And I want to bring Elmi back in because I actually had the opportunity to read some of Elemi’s op-eds before this session before this recording, and you wrote about indigenizing the curriculum. So, can you tell us about the process of how you went about writing -I think it was 400 or 500 words- it wasn’t that long. Can you tell us a little bit about your experiences writing op-eds?

Elmi Slater 14:01

Yeah. So, in learning about op-eds like two months ago, but previously no knowledge of what that was even though I feel like I’ve read many, we were told that we could write an op-ed pinion piece on any subject of interest, and kind of in doing so I was just kind of exploring recent things. And it was just prior to the referendum. So, I was really thinking about that, but I didn’t want to write about that because I felt like there were already so many voices being heard. And I wanted to kind of highlight another issue that kind of was brought to light within that as well. And that was indigenizing our education system. I think, in learning what indigenizing is, you have to learn the difference between indigenizing and decolonizing. With my previous teacher, Holly, the same course we kind of had a discussion in this as a class and it really kind of opened my eyes up to what these two words mean and the different definitions. So, decolonizing is just the undoing of like colonial elements and removing those whereas indigenizing is actually incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing, doing, and being. It kind of moves beyond what can be kind of seen as tokenistic or just an acknowledgement, and it actually informs meaningful change. And in context of education and the curriculum, I was just thinking about how while Indigenous histories and culture is a cross curriculum priority but there is nothing in place to ensure teachers do that for one. And second, it’s maybe perhaps considered more decolonizing like the way teachers deliver this. And it’s not actually changing the system that we teach. And through my indigenous culture and languages class, learning from country, learning in a more multi-modal way, involving forms and different things that kind of move beyond just literacy and numeracy. I was kind of reflecting on that in writing the op-ed, and my own personal experience within that class, and then within all my other classes in a Western education system. And so, when I began writing the op-ed, I realized it was really hard -I find writing very hard. And I found it almost more difficult to kind of sit down and write something from opinion because I was so used to writing in a more analytical lens. But once I kind of got the hang of it, I found it really empowering. And I also found benefits, like I learned more about the topic that I was actually looking into. Because like Pasi said, you can’t just have an opinion piece with no facts behind it. It made me more informed on what I was trying to say, like have my voice heard, but like a stronger voice that’s backed up with like -and another thing I think is cool about opinion pieces is how you can involve anecdotes and more of a personal experience in them too. And I think this combination of facts and opinions and anecdotes, that format really stood out to me. And I think in writing one or two, it’s become a practice that I really enjoy. And yeah, especially on topics like indigenizing the curriculum and stuff like that that I think is really important.

Pasi Sahlberg 17:05

Can I throw in one reminder that any op-ed writer, or anybody if you’re teaching your students to write op-eds, have to keep in mind. I think this was something that Mark Twain said, he said something like “I would have written you a shorter letter, if only I had more time to do that”. So, when you do something like that, you realize that writing a short piece takes much longer. Again, referring to my students’ experiences, everybody says the same thing. That it’s so much faster to write 25 pages or something than 400 words of something that’s really, really important.

Will Brehm 17:31

And Pasi, I want to ask about -yes, it’s difficult to write opinion pieces, you can do a lot with it, you can have a different voice, Elmi was talking about. What about reach? How wide can you reach an audience with op-ed writing?

Pasi Sahlberg 17:46

You know, the sky is the limit in this space. And I’ll give you a couple of examples. I was writing op-eds for The Washington Post for many years when I was living in the United States. And I once wrote, probably about 10 years ago, it’s still available there. I wrote a little piece called -and this was in the middle of this teacher wars and fights in the United States. And everybody was saying that Finland has these amazing teachers. It’s easy for you to say this and that because you have these great teachers who can turn around everything. So, I wrote a kind of a piece for that conversation. If you read that, you need to understand the context that it was not just written for something. It was written as a response to these kinds of false ideas that is all about teachers. That if we just have world class teachers in our schools, here in Australia, everywhere else, actually we do have, but in many countries, we don’t have everything would be fine. So, I wrote this little piece, I think it’s titled, “What is great Finnish teachers taught in your schools”. And basically, my question was, what would happen if we make a kind of an imaginary experiment and choose one state in the United States, and let’s say or Indiana, actually, because it’s about the size of Finland and many things are similar. Export all the Finnish teachers there in Indiana, and then bring all the Indiana teachers back to Finland, and let them do what they do in the schools and cultures for five years and see what happens. Just as a kind of a curious experiment. So, I went on with this idea, but my conclusion was actually nothing much would happen differently. That most of the Finnish teachers in the state of Indiana would have probably left teaching because they would say that this is not what I was prepared to do. That I was not prepared to, to prepare these kids every year to the tests and do some crazy things on them. And in Finland, the PISA results or any test results probably would not go that much lower only because of having these Indiana teachers there. And it went viral, this little op-ed piece, and within months, it was read by according to the editor of The Washington Post by one and a half million people, and now it’s about 3 million people who have read that piece. Okay. So, my question to anybody who’s writing journal articles here, is when was the last time when you had one and a half million readers of your journal article. I happen to sit in a number of editorial boards, when every year when we look at what has happened. If somebody has had 300 hits online in your article, it’s a well done. It’s a really well done. So, that’s the kind of a scale that we’re talking about. And I’m often using this also as an example of what can happen if you have a kind of a good piece at the right time to the right audience. That so many people come back to me, and some even come back to me with the money saying that this is so important thing that, could you do a little bit of research on that, and, you know, compare this and that, and we’re happy to give you money to do that. And they wouldn’t do that without this opinion piece. So, you never know what’s going to happen if you happen to be in a kind of a right place at the right time. But you need to know how to tell the story and what people really need to hear about this. The other one I wrote just a few years ago, just at the beginning of the pandemic. There’s a thing, you probably know this Will, the Shanker Institute. There’s a Shanker Blog in the United States that many people read. It’s very well read among American educators. So, in the week, I wrote a piece about five things that we should not do when we return back to normal from COVID. Kind of a quick. It took about two hours to write that; I did it very quickly. I sent it there because they requested me to do that. And within the first week of online, it had 150,000 reads. So, this is what we’re talking about here. If you care about impact, if you care about people having your ideas and think about them, and look at the resources and evidence that you show there. You know, these are what we should do much more than what we are doing right now. But if you don’t care about those things, if you’re happy with celebrating 300 hits in your journal article every year, let’s go for it. Again, I think it’s also about how do we see ourselves and our roles. And I don’t want to undermine anyone who is writing journal articles, even if you have 300 hits, I think it’s an important thing to do. But you know, I see myself as a changemaker. That’s what I do in policy, in research, and in practice. And that’s why for me, it’s critically important that whatever I write that somebody reads out there. And when somebody reads, I’m even happier when somebody reads what I write, and they get back to me, even if they get back to me and say that I completely disagree with what you say, or you’re wrong with that point. But I know that something has happened somewhere when people react like this. So, it’s also very much about how we see ourselves as academic researchers and practitioners. And you may see yourselves in different ways, and that’s fine. But what I’m talking about here is more about how I see my own role and our work.

Will Brehm 22:10

I think it’s important not to also just glorify the op-ed. I think thinking about knowledge dissemination in an academic space needs to be beyond the op-ed as well. And I actually think about Elmi’s mother, who is an artist-academic or academic-artist, I don’t know exactly how to refer to you, Naomi, but artistic expression also has impact beyond and in a wider realm, similar to an op-ed, but also very different than an office. So, Elmi, when thinking about your mother’s sort of artistic life and her educational life and trying to balance both, how do you see artistic expression and art in the world of knowledge dissemination and creation?

Elmi Slater 22:50

Yeah, that’s a really good question. I guess I feel kind of contradictory of myself when I’m talking positive about literacy and writing op-eds. I feel like much of the Western system does put such a heavy emphasis on writing, but I think we also neglect art forms as well, and art being more of a critical pedagogy. And I think through my experience of education and learning, I’m a very visual person as well. Not everyone kind of learns in the same way. And I think because art is such a universal thing. Among all cultures share different art forms. It’s something that everyone can do, it’s accessible. And I’ve seen firsthand through classrooms, students engage more when their learning through an art form. I engage more when I’m learning through an art form. And I have the privilege of having an artist mother and teacher, but not everyone has access to that, I guess. And yeah, so I do think it is really important to integrate arts across all subject areas.

Pasi Sahlberg 23:49

You know, we can also see that the academic writing or writing in general can be an art form. But again, I would ask how often is the academic writing that we all know well could be seen or viewed as an art form? For me, the typical way of writing academic stuff is much more kind of a linear thing; that you do one thing, and then you move to another one, and somewhere there in the end of the line there is a publication, and that’s where this kind of story ends. But you know why I’m so passionate about writing, particularly op-eds, a kind of a journalistic style art form is that -and this goes back to what I did, and always do with my students. And some of my students like my Harvard students, all of them they say that they have never, ever had an experience like what we did in my courses, because of this thing. That when they submit the assessment task -and assessment task here of course, means what you are required to do for the course, that was the op-ed. And I say that you can submit your assessment tasks as many times as you want during the course. It’s not just a one submission that’s just five minutes before the deadline like most university students do, and then you read it and you give them feedback. I say to them do it as soon as tomorrow if you want to do that. I’m going to read it and give you feedback. Or I’m going to send it to somebody else who’s going to give you feedback. You write a next form, and its exactly how art works, right? That you do a painting or sculpture or poem, or song and you’ll go back to that, and you can improve it a little bit. You played or look at it or show it to somebody and say, cool, but this is something that you could do differently. You go back to that and write. But in academic writing, we rarely do that. That what students learn in school, and then at the university is that you do something, and you show whether you can write or think or know things and then you get feedback and cradle that and there’s nothing you can do about it. But what we can do when we teach students how to write, we can use it as an art form in the sense that you learn to work on your piece, this 400–500-word piece, and you give it back to me, and I give you feedback, and we talk about it, and you go back to your piece and improve it. And that’s the experience that I was talking about that almost all of my university students say that they have never had anything like this in school, nor the university. And I think that this is exactly how the learning how to do things should be. That it’s a kind of art form that you do, and you learn to love that and then you improve it and own it.

Will Brehm 25:52

But it is also beyond the written form, right? So, Pasi, when you walked in, you were carrying a guitar case, right? Ricky is here from Amplify Music, who also has his guitars and will be having a musical event later today. And you and Rick, you have done conferences where you bring music into that academic space. Why do you do that?

Pasi Sahlberg 26:12

I don’t know, actually [audience laughter]. Maybe it’s because it’s a really good friend. And you know, Ricky has taught me so much about the power of music and how music can engage things. I think I’ve probably told you something about education and these things. But you know, I’ve been doing this so long. First, I used to do these “death by PowerPoint” presentations, where you have 50 different beautiful slides and everybody’s sleeping but I was still talking a lot. Now, I’m not doing the PowerPoints that much, but I still talk a lot. None of those things are really going through so well that people will kind of get an emotional experience about what we’re talking about. But now, with him, we have started to do this kind of a keynote presentation -it’s not a keynote- but it’s a presentation where we combine performing music and the spoken word and storytelling about education. We talk about very important and critically, sometimes painful things. But when we blend those things with music with the people’s experience, particularly when it’s a music where people can connect themselves, like we do Tom Petty and the Foo Fighters, you know, that type of music that people can sing along. And Ricky knows this much better than I do that how people feel when they kind of become part of the storytelling. And then they’re speaking to all these painful stories about education. They go home, and they think about this little bit. And we did a big gig in Sydney about a year ago, and anywhere we go where there are primary school teachers in this country, there’s always somebody who said, Oh, you guys we’re playing music over there. But not only that, many of these people say that and I remember what you were saying. I remember what the message was. And I meet a lot of people say that I saw you speaking there, and I say, so what did I speak about? Well, I can’t remember that, but you were there. I remember your shoes. But you know, that’s the power of music everywhere that it kind of brings people together, it gives people something that they can connect to and again, own these things, and remember, and that’s when it kind of begins to turn into the change. Remember, I’m a change maker here. So, if you ask me Why do I do this, I do it because I think that this is a one way to move along of this pathway to trying to change things. Trying to help people to change how they think about these things, and how they think about themselves as well. I’m always telling my audiences the same thing that that you guys you know much more than you think you do. But without music, it’s a difficult to get that. We often with Ricky, we say that you actually can do much more music than you think you can do. If you stay here long enough, today, you will experience the same thing; that you actually are musicians or we are all artists, we are all creative people, we are all academics in the sense. We just don’t know that yet. That’s why it’s so important to move away from these kinds of a traditional ways of doing things. So, for me, it’s really the little bit similar way that I still write journal articles. I love to do that. But I only write if I know that people will read it. I still speak about things if somebody asks me to, or invites me to speak. But I try to do things in a different way. I also do different storytelling because I think that that’s important. So, again, it’s my way of thinking and doing about these things. And I understand that people have their own things. So, let’s be different because that’s exactly the beauty of this type of world; that we are different people doing things in a different way.

Will Brehm 29:06

So, to end the conversation, I want to think about, you know, how do we actually do things differently? A practical step and I thought Elmi, what would you recommend to an audience of academics who often are researching you and students As a student, what would you tell back to the audience and the academics how to do things differently? What would be a first step?

Elmi Slater 29:27

So, firstly, I think a lot of teachers are very apprehensive about including Indigenous ways of knowing, doing, and being but I also think if you are willing and want to incorporate these different ways, you just go out of your way to research, find the right resources. I would like to see more change in classrooms. A positive thing I’ve had from my indigenous culture and languages class is actually doing a lot of my classes outside on country and things like that is really helpful. Doing more classes that just literacy. Like other mediums, like multimodal. I actually think being able to translate your knowledge into a visual or audio mode shows like a higher thinking. And I think that’s a really good skill. And I like seeing that being cultivated among my peers. And speaking on the indigenizing the curriculum thing, I’ve noticed that some teachers incorporate things, and they might not be informed, and sometimes that leads to cultural appropriation. But going on from that, don’t be apprehensive to not include it at all because you’re scared to do cultural appropriation. I think speaking to teachers, like Eli, other teachers within that area, I know that there’s a lot in the UC faculty, elders, people in community, First Nations students is really important. It is important to include those ways of knowing, doing, and being in teaching and different modes. I’d really like to see more of that kind of, and I think, overall, the benefits is like a more inclusive and accessible way of learning. And I think it benefits both parties, too. But yeah, I don’t know.

Will Brehm 31:04

And Pasi, what would be the recommended first step for this audience, but also the audience that might listen to this podcast in the weeks and months and years ahead?

Pasi Sahlberg 31:13

Yeah. I think probably particularly the audience like this, that we are in a great university here, and you guys you are working with the younger generation of educators; I think the question we really need to ask much harder and most often that we do is that what is graduates that you send to the world of work, what do they need? What are those fundamental foundational skills as educators that they need? And I think that the answer to this question is very different today than it was 10 years or 20 years ago. I would actually invite everybody to start on that question that what are those things that every graduate in your faculty or mine, what do they need to know and be able to do? And you know, the answer can be different. But communication is one of those things that everybody needs a very different communication skills as an educator. Whether you’re a classroom teacher, or principal, or dean of the faculty, or anything, you need to be able to communicate very, very differently than before. The whole different conversation would be to talk about the artificial intelligence that how it’s changing many of these assessment tasks like you colleagues, you know, this as well as I do that it doesn’t make any sense anymore to ask students to write a 3,000-word essay about something because everybody will use a ChatGPT or something similar to do that. So, we need to really think about what the machines cannot do that well, and then make sure that we’re asking students to do things that can help them to understand how to not only live with this new world of technology, but how to work with the technology in a way. But I think the starting point would be that this question that we need to be clear about what do we think that the graduates of your faculty need in their work? And then make sure that they have all those foundational skills that we think they do. For sure they need knowledge and understanding about many of these things that we teach them here, but there may be some things that we haven’t thought about that much. And I’ve been speaking about what I think all my graduates, or my students need to know, and I will continue to do that because I think it’s important.

Will Brehm 32:58

Well, Elmi Slater, Pasi Sahlberg, thank you so much for joining FreshEd. Thank you for being here at the University of Canberra [audience clapping].

Want to help translate this show? Please contact info@freshedpodcast.com

Related Guest Publications/Projects

Pasi Sahlberg website

Why students need to know how to write an Op-Ed

“What if great Finnish Teachers taught in your schools”

Five things we shouldn’t do when schools re-open –

Pasi’s OpEds for Washington Post

Mentioned

Academic publishing statistics

Number of academic papers published per year

Open access publishing statistics

List of education journals

How to write an Op-Ed or column

Creative ways to disseminate your findings

Albert Shanker Institute blog

Recommended

And now a word from Op-Ed

Opinion columns and editorials

Tips to improve the visibility and dissemination of research

Rise in higher education researchers and academic publications

Research in education draws widely from the social sciences and humanities

Mapping global research on international higher education

Have any useful resources related to this show? Please send them to info@freshedpodcast.com