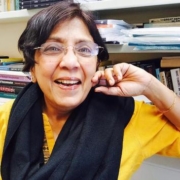

Audrey Bryan

Teaching the Climate Crisis

Today we discuss the climate crisis, why it’s a difficult knowledge for humans to grasp, and how art can help us transform approaches to teaching about it. My guest is Audrey Bryan.

Audrey Bryan is an associate professor of Sociology in the School of Human Development at Dublin City University. Her new article is Pedagogy of the implicated: advancing a social ecology of responsibility framework to promote deeper understanding of the climate crisis, which was published in Pedagogy, Culture & Society.

Citation: Bryan, Audrey interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 282, podcast audio, June 6, 2022. https://freshedpodcast.com/bryan/

Will Brehm 1:07

Audrey Bryan, welcome to FreshEd.

Audrey Bryan 1:09

Thanks so much. I’m delighted to be here.

Will Brehm 1:11

So, can you tell me why the issue of climate change is considered a difficult knowledge?

Audrey Bryan 1:17

Well, that’s a great question. Well, I think the most obvious reason is that the scale of the threat posed by global warming is so enormous that it’s cognitively very difficult to comprehend or to get our heads around. We might know, on some level, that the ice is melting at an alarming rate in the Arctic and Antarctic circles. We might know that this has the potential to spark catastrophic ecological tipping points but the enormity and gravity of it all makes it extremely difficult to accept this as probable or even possible. So, because many of us don’t want to know that these things are happening, we turn away from the reality of what we’re faced with. So, humans have this incredible capacity for disavow, which is the ability to at once know something and not know it at the same time. And whereas, I mean, many of the effects of climate change are being more acutely felt in recent years, and it’s more palpable, and we now have phenomena such as ecoanxiety, we don’t quite yet know how to make sense of, or deal with this psychological impact because it’s such a new phenomenon. And furthermore, its effects are often under-acknowledged or not even spoken about. So, I think this is one of the main reasons why it constitutes such a difficult form of knowledge.

The other issue then has to do with how we’re positioned in relation to the climate crisis. So, all of us by virtue of being human beings on planet Earth are at once vulnerable to, as well as culpable for, the climate crisis. Now, you know, that’s very much a matter of degree depending on where we’re located and what the size of our carbon footprint is, for example. However, it’s this kind of combination between vulnerability and culpability that makes climate change such a difficult form of knowledge. So, many scholars are now characterizing climate crisis as a form of eco trauma to capture, I suppose, the complexity of our positioning within this crisis. And it’s the idea that the damage and the harm that many of us, particularly those of us in the global north, who are living in emissions intensive societies, the harm that we are inflicting on the natural environment is essentially coming back to haunt us in the form of eco trauma. The idea that all of us living in emissions intensive societies bear at least some responsibility for the climate crisis was kind of the starting point for the article. And it’s this notion that we can’t escape our own implication or complex entanglement in the crisis. And this can often spark, you know, fairly difficult and painful emotions. So, it’s difficult in that sense, as well.

Will Brehm 4:26

I’m trying to reflect on this difficult knowledge as you very clearly sort of begin to articulate it vis-a-vis climate change and trying to reflect on my own sort of self here. You know, I have family in Australia. I would love to go and fly and go to Australia. And so, on the one hand, I can do that and buy the ticket and go to Australia. But of course, that emits a lot of carbon and contributes to this climate change. And I, also at the same exact time in my head, I have seen the devastating floods in Australia, which are most likely connected to some extent to climate change. And these two realities -it’s sort of like I am culpable. But I’m also, I guess a bit in denial, because I’d like to go to Australia and see my family.

Audrey Bryan 5:08

The concept of normalized denial is probably one of the best ways to capture that internal tension and conflict that you speak to. So, on the one hand, we have this conscious awareness that our individual actions are consequential in terms of causing harm and suffering to others. But it’s very easy to kind of negate or ignore that reality when we have to, I suppose, justify our perpetuation of those harmful practices. So, I like this notion of normalized denial because, I suppose, it makes very real, the reality that ordinary, everyday practices that we engage in, that are socially state-sanctioned, many of them are expectations or requirements even. It could be something as simple as eating meat, you know, going on a vacation, or a holiday, or driving a car, that these, whereas in and of themselves, they’re not that consequential, but in the aggregate, and that their cumulative impact is indeed, highly consequential. And so, the idea of normalized denial, and grappling with the consequences of that, I think, is a helpful way to think about these tensions and conflicts that we experience in relation to the climate crisis.

Will Brehm 5:25

How do we overcome some of this normalized denial? Because obviously, it seems like there’s a struggle between simply blaming individuals for doing, as you said, individual practices, which in and of themselves don’t seem that consequential but are embedded within this larger system and social structures that are causing tremendous harm and problems worldwide, and unevenly. And those who are probably contributing more to the problem are feeling less of its effects. How do we begin working through these tensions between the individual and the sort of larger social structure vis-a-vis this difficult knowledge of climate change?

Audrey Bryan 7:06

Yeah, I mean, I don’t think it’s straightforward. You know, this was kind of the impetus for the article -kind of derived from a frustration that I myself have experienced, you know, either listening to or participating in debates within climate action and within education, where on the one hand, you have people who are sort of privileging this very individualistic narrative and highlighting the need for individual transformation. And then on the other hand, you have people who are sort of saying it’s all about the ideologies, the structures, the kind of easily identifiable bad guys, you know. And I think that’s completely understandable. You know, when you think of global corporations like Shell or Exxon, they’re very much in the public eye. Just for example, I think just yesterday, in Massachusetts, it was announced that a legal challenge is being taken against Exxon, I think it is for deliberately misleading the public. Those kind of global, multinational, those carbon major companies are very much in the public eye. We’re very aware of disasters such as the Deepwater Horizon disaster back in 2010. I suppose it’s so visible, the damage and the havoc that they wreak. The environmental destruction is so palpable because we can see it on our television screens. And we see that there is this easily identifiable culprit.

And ultimately, the research evidence suggests that there are a finite number of major entities, companies, governments who are responsible for a majority of the CO2 emissions, and that that has happened within a very short space of time. So, on the one hand, we have these easily identifiable culprits. And then, on the other hand, we have ourselves. It’s very hard to kind of disarticulate our individual practices from those larger structures that within which we’re embedded as you have said. So, it isn’t straightforward, I think, in terms of looking at the linkages but that was really my rationale for writing this article because I didn’t find that the debate is a particularly productive one. It tends to be highly polarized, you know. So, I wanted to look at the interrelatedness of these different scales or dimension. And that the argument often quickly descends into -on the one hand, you have people who are saying, “Well, if we privilege individual actions, that’s necessarily at the expense of really interrogating broader structural ideological factors that are at play”. So, for me, it was about, I suppose, looking more holistically at the problem and looking at how everything is interrelated. So, with that in mind, I tried to devise a conceptual framework that places the individual kind of at the heart of a much broader, I suppose, macro system.

Will Brehm 10:13

Is this what you call the implicated subject?

Audrey Bryan 10:15

Yeah. Well, I draw quite heavily on the work of Michael Rothberg, who’s a holocaust and memory studies scholar in the US. And he devised this conceptual framework of the implicated subject. He uses it primarily in the context of looking at racism within the US. So, I have drawn on that framework, and I have found it very helpful. It’s a really useful tool or way of thinking about individuals’ own complex involvement, or complicity in larger systems and structures of injustice. So, he kind of delineates between more direct forms of implication. So, he talks about historical forms of implication as well as more contemporary forms. And he also delineates between more direct forms of implication and then more indirect. So, an example of a more direct form of implication would be if I was, let’s say, the descendant of a slave owner, okay? So, he talks about genealogical implication. And then he also talks about structural implication. So, that kind of pertains to where I’m located or positioned within the social structure. So, for example, if I’m white, middle class, I have various advantages, or I’m a beneficiary of a larger class-based, racialized, hierarchical social system. And it’s about getting us to think about our responsibility, our kind of ethical and political responsibility within systems that are stratified along racial lines, gender lines, ability lines, and so on,

Will Brehm 12:03

How does that connect then to the climate crisis? Like, if we think of the implicated subject and these social hierarchies, you know, how does that help us think through this difficult knowledge of the climate crisis?

Audrey Bryan 12:17

So, part of it is about, by placing the implicated subject at the center of this wider system. It’s about being able to see our role as a perpetuator of climate related harm and climate related injustices. So, it allows us to see the ways in which, by virtue of the ordinary everyday harms that we’re involved in -you know, the examples I gave earlier. How our involvement to those harms positions us as perpetrators of climate relation injustices. So, I’m referring here, I suppose, to people who are based in an emissions-intensive society. So, we’re not just beneficiaries of consumer capitalist society, we’re also perpetrators of harms through actions and our participation or our conformity to social norms. It could be in terms of the blind eye that we turn to our governments when they endorse harmful practices, when they fail to take appropriate climate actions, and so on and so forth. So, it’s about the actions that we take, it’s about the behaviors that we are involved in but also our failure to act. Or our failure to hold government officials to account when they themselves fail to act or engage and devise policies that allow these so-called dirty industries or carbon majors to continue to wreak environmental havoc.

Will Brehm 13:52

One of the issues that you bring up in the article is sort of this problem of intelligibility. It’s just very difficult to represent in any sort of understandable way -issues around climate change and the climate crisis. And the framework helps us begin to get a sense of our own sort of connection to it within these larger institutions and structures and social hierarchies. But in terms of this issue of representation, you point to art as a potential way to sort of overcome some of these problems of intelligibility. Can you explain how art may help us in understanding issues around climate change a little bit more easily?

Audrey Bryan 14:31

One of the difficulties of the climate crisis is that it has this kind of intangible quality to it. So, its effects are often invisible, they’re ongoing. It’s often described as a form of slow violence. Rob Nixon coined this phrase slow violence to talk about the imperceptibility of climate change and to address the challenges of apprehension associated with it. So, it’s a problem of intelligibility in that sense because people find it so difficult to fully understand the causal connections between their own actions in one part of the world and the harm that this can cause elsewhere. But for me, I suppose art serves as a really valuable -it’s a critical tool in the sense that it’s one of the few tools that we have that enables us that kind of, combines cognition, criticality and, and effect simultaneously. So, because the climate crisis can be so emotionally charged, and because it’s so affecting, I think we need visual tools, not least, to kind of enable us to make the inexpressible expressible, to make the invisible more visible, but also to equip us with stimuli or to serve as a springboard through which to really interrogate the more affective dimensions of this crisis. So, I think for me, art is one of those realms where it enables us -you know, where science is very good at capturing what is and documenting the way things are with something that constitutes such an existential crisis, we need tools that will enable us to think otherwise, or to imagine things otherwise, and an art has that freedom, I think, and it allows, it’s that kind of expansiveness. It allows us to go there. So, it’s a really valuable tool in that regard. And, you know, now we have, I suppose, an emerging genre of climate change art and of climate change literature. And, I think, as educators who are interested in teaching about the climate crisis, there are increasingly resources out there. Whether it’s literature, whether it’s film, whether it’s art installations that we can draw upon to, I suppose, try to give more tangible form to this otherwise very abstract and unknowable phenomenon.

Will Brehm 17:12

It’s interesting to use the word abstract, because at the same time -I mean, listeners won’t be able to see this, but- we’re talking on a zoom call and behind you on the wall is a print of Sonia Delaunay’s abstract work, and it’s quite beautiful, and does invoke certain emotions and feelings when I even look at it through the screen here. And in a way, it makes me think, with art, and around climate change art, for instance, if that’s a theme of art now. Even though it’s supposed to try and help us understand this really abstract concept of climate change, perhaps abstract art can actually help us with that, in a weird way, right? It doesn’t have to be literal representations of climate change as art, but it actually can sort of embrace abstraction to evoke a particular affect.

Audrey Bryan 17:57

That’s a really interesting way of thinking about this. I mean, when I started to delve into what artistic resources are there, it did, sort of, evoke for me questions around like some of the artworks that I looked at. So, one of the kinds of key genres is this kind of ice-related art. So, there’s a lot of art installations where you can actually get up close and personal with melting ice. You can embrace the melting ice; you can mourn the melting ice. And it did get me thinking, you know, what are the most affective, like effective as well as affective forms of climate art? And some of it I found has the tendency to overwhelm or to rather kind of distance us rather than animate us. So, I think it depends. I mean, there’s one piece that I really like, which is called Pyramids of Garbage and it’s an art installation that has been created by an artist, Bahia Shehab, in Cairo. And the reason why I really like that is because it really invites us to think of ourselves as agents in this crisis. So, rather than some artworks which I think have the potential to sort of disempower rather than empower us, this piece by Bahia Shehab, which is kind of juxtaposed with incredible, Great Pyramids of Giza, really forces us to critically self-reflect on our own engagement with the crisis and invites us to see ourselves as agents with the capacity to ameliorate and to imagine a radically different future and set of ideologies that guide and drive us. And so, for me, that’s a very empowering set of images, and maybe some of the abstract work that you allude to there has that capacity because it really speaks to imagination. It speaks to this notion of things being otherwise, it speaks to the notion of potential rather than closing things down and maybe shutting us off from those possibilities.

Will Brehm 20:13

It’s a really interesting sort of entry point into thinking about, as you said in the beginning, this difficult knowledge that sort of has normalized denial built in and people try and resist it and not think too much about it and sort of go on with their daily lives. And art can sort of disrupt that and open new possibilities, new worlds, emotions, feelings, you know, you name it, tangential thinking. So, how then, does that actually get brought into classrooms, get taught? How does it impact, sort of, the word you use in the article is the teachability of climate change? How do we see this connection with art and climate to teaching and learning?

Audrey Bryan 20:49

I think its value lies in the ability to kind of document what is otherwise invisible, intangible. So, for example, we now have this kind of emerging phenomenon of glacier funerals. So, there’s these attempts to make what’s intangible more tangible. And for me, whether it’s specific climate related artworks, whether it’s literature that addresses the climate crisis, whether it’s film, it can even be approached in a very playful way in the classroom. So, a lot of the work that I do, in my kind of teaching role, I work with teachers who are preparing to become primary school teachers, and many of them work with very young children -children as young as four years of age. So, I’m frequently confronted with this question and grapple with it myself, in terms of, to what extent is it appropriate to be engaging very young children with the trauma that is climate change? And I think it’s a very reasonable question. But there are these kind of dominant sort of discourses that I think cloud kind of productive engagement with that. Whether that’s sort of a discourse around, “Well, is it developmentally appropriate to be exposing very young children to such challenging and traumatic forms of knowledge”? And that sort of tends to sit alongside a discourse of childhood innocence. And yet, we think about how children, even very young children, are immersed in a very hyper consumerist world. We kind of have to think more critically about that narrative of innocence. So, for me, one of the key ways into that is to do it, playfully. So, it’s almost like a sort of a slantwise engagement, if you will, with these very difficult forms of knowledge. And there are resources out there. One of them that I like to use is a film that’s like a Disney Pixar film, that’s probably about 10 years old now. But it’s called Wally. And it’s like a wonderful engagement with hyper-consumerism and our role in basically destroying the planet.

Will Brehm 23:01

In Wally, isn’t there, like landscapes of used electronics, and Wally is a character that is like a robot or something, and he’s sort of wandering. It’s silent too, or there’s very little dialogue?

Audrey Bryan 23:13

Very little dialogue. And he’s tasked with basically cleaning up all of this garbage and that’s kind of his entire existence. But it’s done in a very playful way, and in a way that is appropriate. I have five-year-old twins, and I showed them certain clips from the movie, and they were really taken by it. So, the idea is that these resources can serve as springboards for these complicated conversations that we need to have, but they also, I suppose, open up the affective realm because I suppose one of the things, I think is most important in this situation is to allow space for emotion to come into the classroom. So, I think, emotion is something that tends to be marginalized within education, and certainly within mainstream educational research. It tends to be viewed as irrelevant. Very much so unless it’s a very prescriptive understanding of emotion in terms of emotional regulation, you know. So, there’s this whole kind of move now towards social and emotional learning but I just don’t think that that does justice to the complexity of the emotions that we experience in relation to climate change. So, it’s about creating space for emotion but also thinking about emotion in more expansive terms. So, we tend to think in terms of guilt, anxiety, grief, and those are obviously very powerful and legitimate emotions. But I think there’s also a lot to be said for having a very expansive understanding of emotion and bringing things like playfulness, humor, laughter back in because let’s face it, this is such an enormous crisis. And we really have to think creatively about how to engage people with it.

Will Brehm 25:11

You know, going back to Wally, if you watch the movie with children and you know, 5, 6, 7, 8 years old in a classroom, and they will most likely encounter various emotions selectively. And then the idea is that you then as a teacher would come back and actually work through the meaning and try to process some of these emotions and relate it to climate change? Is that sort of how this example would work in the classroom?

Audrey Bryan 25:37

Yeah, exactly. I’m really taken with this question of what purpose do emotions serve? So, this idea that emotions reside within us, and that they’re very individual, they’re very personal to me, I don’t think is an especially helpful one. So, some of the more interesting recent literature around emotion talks about the circularity of emotions, how emotions do things. So, it’s more about emotion as an action rather than a quality that I possess, for example. And within the Irish language, the direct translation for emotion is, “I have an emotion on me”. So, if I say “ta bron orm”, that means there is sadness on me, which I think is a really interesting way to think about it because it suggests that there is nothing inevitable or permanent about having difficult emotions. This is where the peace around agency comes in and being able to, I suppose, transcend really challenging emotions through becoming involved in climate action, through changing one’s lifestyle, and so on. So, it’s the notion of individual agency and power to affect change because really, climate change education has to be transformative. For it to be effective, it has to be transformative on multiple levels. So, yeah, I like this idea that there’s nothing permanent necessarily, or inevitable about the emotions that we will experience as we delve deeper into the climate crisis and our own, I suppose, implication in it. The idea that those emotions can be somehow transcended or transfigured and put to political and ethical use.

Will Brehm 27:30

Well, Audrey Bryan, thank you so much for joining FreshEd. Really a pleasure to talk today and I love this idea of emotions being on me rather than in me. It’s fantastic.

Audrey Bryan 27:40

Thank you so much. Such a pleasure.

Want to help translate this show? Please contact info@freshedpodcast.com

Guest Publications/Projects

Affective Pedagogies: Foregrounding Emotion in Climate Change

Climate Change Education in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development

Development Education, Climate Change and the “Imperial Mode of Living’”

Mentioned Resources

Eco-anxiety

Climate trauma

Deepwater Horizon disaster 2010

Michael Rothberg – Implicated subject

Sonia Delauney’s artwork

Pyramids of Garbage – Bahia Shebab

Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor – Rob Nixon

Glacier funerals

Walle – Disney film

Recommended

Glacial Deaths, Geologic Extinction

The Moral Side of the Climate Crisis: The Effect of Moral Conviction on Learning about Climate Change

Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis

Artistic Activism Promotes Three Major Forms of Sustainability Transformation

A Study on Climate Change Art at the ArtCOP21 event in Paris

Teaching the Climate Crisis: Existential Considerations

Exploring the Transformative Potential of Everyday Climate Crisis Activism by Children and Youth

The Role of Schools and Teachers in Nurturing and Responding to Climate Crisis Activism

Teaching about our Climate Crisis: Combining Games and Critical Thinking to Fight Misinformation

Climate Crisis Learning through Scaffolded Instructional Tools

Multimedia Resources

Movies That Teach Kids about Climate Change

Climate Change: Books for Kids

Have any useful resources related to this show? Please send them to info@freshedpodcast.com