Large-scale assessments such as PISA have profoundly changed the processes of educational policy making. Countries that do well on PISA are turned into reference societies by other countries trying to emulate educational success.

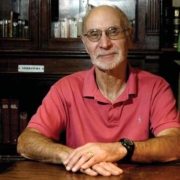

My guest today is Florian Waldow, a professor of comparative and international education at Humboldt University in Berlin.

One of Florian’s main research interests is the study of educational “borrowing and lending”, particularly the ways in which countries point to experiences from abroad as a way to legitimate policy agendas and how educational “reference societies” are constructed.

In today’s show, Florian talks about how the German media has interpreted the PISA success of countries in Scandinavia and Asia. His research shows that reference societies can both be positive and negative — pointing towards education reforms Germany should enact and those it should not.

The research discussed in this podcast was published in 2016 in the journal Zeitschrift für Pädagogik.

Full Citation: Waldow, F. (2016). Das Ausland als Gegenargument: Fünf Thesen zur Bedeutung nationaler Stereotype und negativer Referenzgesellschaften. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 62(3), 403-421.

Photo credit: Eric Lichtscheidt

Citation: Waldow, Florian interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 27, podcast audio, May 9, 2016. https://freshedpodcast.com/florianwaldow

Will Brehm 1:33

Florian Waldow, welcome to FreshEd.

Florian Waldow 1:37

Yeah, hello. I’m really thrilled to be here.

Will Brehm 1:40

Why is Finland considered the poster child of education reform?

Florian Waldow 1:47

Well, in the first, I think that has a lot to do with PISA and Finland’s PISA results. But that’s not the whole story. As probably most of the listeners know, Finland was close to the top of the league tables in the first round of PISA. In fact, it was number one in reading literacy, and I don’t recall which positions it was in in scientific and mathematical literacy, but also quite high up. But I think that alone would not have made Finland the global poster boy of educational reform. Because if you look at the league tables of the first round of PISA, you’ll see that Japan and Korea already then were on first and second place respectively. I don’t recall which one was first and which one second, but one was first and the other second, and the other first. And the first one, first in mathematical and scientific literacy. So, other countries were very, very successful as well. And I think that Finland in a sense, could build on an earlier history of Scandinavian countries being considered models in the fields of education and welfare. After the Swedish comprehensive school reform of the 1960s, there were bibliometric studies that tried to map how attention for and interest in Swedish comprehensive school reform was distributed around the world. And you saw that there was a massive amount of interest in Swedish comprehensive school reform, particularly so in West Germany, but also in other countries. So, there is a long history of interest in school reform in Northern Europe. And seen from the outside in very many locations, there is this kind of transnational stereotype which all the Nordic countries are seen as belonging to.

So, while if you ask a Swede or a Fin, they will very often emphasize the differences between Sweden and Finland. Seen from the outside these differences often become quite blurred. Reference societies such as Finland are used as projection screens for the projectors’, as it were, own conceptions of the good school. And there’s also research on how much people know about other countries. And what usually emerges, cutting a few corners, is that they know quite a lot about their own country, possibly something about one or two neighboring countries and also, all around the world a lot of people know a lot -or at least think they know a lot- about the USA. That’s kind of usually the pattern that emerges. But what you can see from this research is that usually the general public knows very little about other countries. And from many other countries, Finland is a good case in point that a lot of people did not know a lot of it. They just knew, okay, it is somewhere up there in Northern Europe. It’s close to Sweden so it’s probably somewhat similar. And if it’s true that people use reference societies to project their own ideas about what good education is, then of course, it’s good if the protection screen is as blank as possible. So, it’s actually harmful to know things. I think a reference to other countries doesn’t work as well if you know a lot about these countries because then reality gets in the way and projection doesn’t work as well.

Will Brehm 5:48

And it seems like the PISA score would actually help in making a blank projection screen, right? Like the idea that you would get some sort of a number on mathematics or literacy. And it in many ways is just completely detached from any context of that country when you are outside of say, Finland. All you see is that Finland is ranking very high and therefore we need to go learn from that education system.

Florian Waldow 6:15

Absolutely. That’s exactly what’s happening. And you’ve got this detached, decontextualized, comparable number. That’s the thing. Gita Steiner-Khamsi has written about this, for example. If you get a league table, the league table will kind of exert a certain power of its own. Or will kind of become powerful just by virtue of being there, of being a league table. And you don’t need to be able to calculate a Rasch model. In fact, you don’t need to have any mathematics -or sort of very, very, very limited mathematical literacy in order to be able to say, oh there’s some other countries up there, and we’re down there. And so, it exerts this kind of pressure in a certain direction even if you have no idea how the league table was made.

Will Brehm 7:10

So, Finland basically became, the perfect combination of the actual reforms that were going on in Finland spoke to a wide variety of political interests from other countries. And they were ranking very high on PISA so as a result, many countries were sending education officials to Finland to “learn” from this high-ranking country.

Florian Waldow 7:38

Yeah. It’s interesting that -yes. I think on the one hand, that’s a completely accurate description. On the other hand, it’s interesting that you say the actual reforms in Finland, because I think what you see in many cases is that what actually happened in Finland is not really that important. I mean, there’s one example that I always use with students which kind of exemplifies this very nicely and that is that when Finland was so successful in the first round of PISA, a lot of countries sent delegations there to, as you say, was supposed to study Finnish education. And there was one article in a German newspaper Die Welt not a newspaper -well, it considers itself a quality newspaper. I’m not sure I share that opinion but nevermind -like it’s not a tabloid. And when the then federal education minister, Edelgard Bulmahn came back from Finland, Die Welt ran an article about, what’s the secret behind the success of Finland? And they say, well, it’s all-day schooling. It’s the fact that the pupils go to school in the morning and stay there until the afternoon. And the article also was written in a way that you think that Edelgard Bulmahn, the minister, also said that. Now the thing is, Germany had a massive discussion about the introduction of all-day schooling at that time. The thing is, Finland didn’t and still doesn’t have a system of all day schooling. So, in a sense, that’s a particularly clear example of projection. They were saying, well, the Finnish success is due to all day schooling, which didn’t even exist in Finland. But the reference as legitimatory argument worked all the same in Germany. So, it’s like –

Will Brehm 9:28

You can make anything up.

Florian Waldow 9:30

Yeah, well, maybe not anything. But it’s a very, very wide scope of what you can make up. But I wouldn’t say that it’s always made up. You can also show examples where they kind of -like for example, individual support for students which does actually exist in Finland. It’s quite strong and is probably something that is one reason for Finnish success. But if you look at how that is built into actual political arguments, you can see that both the advocates of comprehensivisation in Germany use it to say, “Well, yeah, that’s what we need in order to have a functioning comprehensive system”. And the advocates of track systems say, one nice quote by a Bavarian educational minister, you know, like Bavaria being a particularly conservative federal state. Yeah, we need individual support, like in Finland in order to make the lowest tracks of the track system work. So, the same feature, as it were, of the Finnish system is built into opposing political agendas there. And another -sorry, I hope that this is not too many examples. But another thing that also shows you the character of this projection quite nicely, is I’ve also looked at Swedish newspapers, how they portray the Finnish success. And now I said that what countries know about other countries is, kind of, they do tend to know something about some of their neighbors. And so, in Sweden, I think the Swedes also project but the projection screen is not as blank. The funny thing is that like in Sweden, Finland is not portrayed as this kind of Pippi Longstocking education place as it is sometimes portrayed from the German perspective, place where pupils learn for intrinsic motivation and there’s no pressure to perform with them. But in the Swedish perception, Finland seems to be much more like a kind of law-and-order place where pupils still do what the teacher says and so on. So, it’s a completely different projection that ends up on the screen that is projected from the Swedish side. So, you’re right. Sometimes it’s completely made up. But I would say more often, it’s not that it’s completely made up but that certain little bits are picked and are kind of built into these projections. So, in any case, it’s much more important what’s happening at the place where the projector stands than at the projection screen.

Will Brehm 12:21

Right, because it’s supposed to advance a particular political agenda.

Florian Waldow 12:25

Yeah. Invent or legitimize already existing political agendas.

Will Brehm 12:29

Right, by referencing a country that is supposedly doing well in its education system by PISA, or at least understood through PISA?

Florian Waldow 12:39

Yes, exactly. That’s it.

Will Brehm 12:41

And so, do these countries that are referencing say, Finland, do they actually copy any of the policy that is found in the Finnish education system? Do they actually, does it result in, say, material changes to education systems in the home country?

Florian Waldow 13:04

Well, again, the problem is a bit what result is supposed to mean here, you know? Because a lot of the things that happen with reference -it’s kind of difficult to identify what’s the cause and what’s the legitimation here. Again, if I may use a German example, the German Standing Conference of Educational Ministers got under heavy pressure after the publication of the first round of PISA results and came out with a list of things that needed to be tackled on the day after the results have been published. So, this was really an emergency measure. And a lot of the things they introduced subsequently had already been planned before. The decisions had already been taken but they had not been publicized widely or they had not had that much support. And you can see that it was kind of more used as a kind of booster rocket for things that were already planned or that were already in motion. So, it’s very difficult to say what was actually copied. A lot of the things that looked like, “oh yeah, this is a copy of this, this is transfer”, really are things that -I just say, often the most important thing is not that actually, “oh, yeah, this seems a good idea, let’s copy it.” But “oh, we have this good idea, let’s legitimate it by linking it to the thing that’s happening over there.

Will Brehm 14:40

Let’s shift the focus from Finland to Asia, the rise of Asia because on some of the more recent PISA testing, places like Shanghai, and Hong Kong, and South Korea have been doing very well on these tests. So, what sort of projections are being put onto the screen in Asia, say?

Florian Waldow 15:09

Yeah. Well, the interesting thing is you said that in recent PISA rounds, Asia did well. The interesting thing is that Asia did well right from the beginning. I mean as they entered PISA, these particular Asian countries -I mean, there are also other Asian countries participating that nobody talks about, but like, specifically, East Asia, Southeast Asia. Yeah, the ones you named. Already in the first round, South Korea and Japan were placed one and two in mathematical and scientific literacy. So, it’s right from the start.

Will Brehm 15:49

So, why do we think of it as “the rise” then?

Florian Waldow 15:51

Yeah. Well, I mean, we think of it as “the rise”, I think, because like, Shanghai only started participating in 2009 and immediately topped all three literacy domains and also, often Shanghai is taken as pars pro toto, like as symbolizing the whole of China. And of course, that’s more than 1 billion people. The Chinese results would look very different if PISA was extended to the whole of China, but I think that’s particularly -and this whole thing gets connected to the discourse of the rise of China as an economic giant and workbench of the world and all these things. So, I think the moment a Chinese region or city like Shanghai enters the picture, this gets kind of more scary for a lot of its economic competitors. What you can see generally, again, like just as with Finland where it’s interesting to look at, what are kind of preexisting stereotypes of Scandinavia, and how’s Finland linked to them. You can do the same thing with Asia and look how that is done. If you look at the North American discussion, you can see that there’s this up and down going from -or it oscillates between fascination and being scared of being a competitor. That was particularly Japan in the 1980s and so on. But that kind of -I think, especially the whole Japan being scared by Japan thing died down a bit, also because Japan went into recession. But with China, that was kind of reactivated I think as far as -I’m not a specialist for the US discussion. But as far as I can see, that’s to a certain extent, what happens there.

If you look at Germany, you can see that there’s a long standing -maybe I should start by saying the education in “Asia”, I hope you can see the quotation marks around Asia, we’re talking about those countries, those Asian countries and regions that are doing particularly well in PISA. The traditional perception as far as there is a traditional perception is that their education is very much characterized by things like rote learning, by grueling examinations, and by pupils mainly revising for university entrance examinations and stuff like that. And in a sense, it’s the kind of opposite picture to what the education in Scandinavia is standing for. And you can see that- with well, what is sometimes termed the rise of Asia, which is probably really the rise in the attention that Asia gets- you can see in the German case that that picture remains unshaken to a surprising extent that you get these articles where people say, “well, okay, so Shanghai is doing great, what should Western policymakers learn from this?” The answer is nothing after things like that. So, it’s really quite interesting. So, you get these articles but in the vast majority they kind of try to shrug off the threat posed by these Asian countries and regions doing so well. That’s not the case in all European countries. If you look at the UK, for example, the current government is running an initiative of importing as it were the Shanghai math teachers that are supposed to show British teachers how to teach math. And they’re also sending groups of British teachers to Shanghai to do the same thing. So, in the UK, there seems to be a different perception there.

Will Brehm 15:51

So, the rise of Asia is about learning best practices from them?

Florian Waldow 15:58

Yes, exactly, exactly. So, they’re not sharing this. No, we can’t learn anything from this. But oh, oh, no, we need to learn from them how to teach Maths.

Will Brehm 20:25

Right. Whereas in Germany, it’s more the conceptions of Asian education, of rote learning, and of examinations.

Florian Waldow 20:35

That is, right.

Will Brehm 20:35

This is something that kills creativity. And we shouldn’t follow it.

Florian Waldow 20:39

Exactly. That’s essentially the picture. And the interesting thing is that you get this picture across the political camp. I’ve looked at the two main quality newspapers, one of them well, center left, the other one center, right. And they tend to disagree on a lot of questions in education such as the comprehensivization issue. But in saying no, Asia has nothing to offer us that we can learn from them, they’re both alike. That’s really quite interesting.

Will Brehm 21:10

And that’s different than the conception of the Finnish education system, where the different camps could compete with a different political interest all justifying it through Finland.

Florian Waldow 21:21

Yeah, that is definitely it. I mean, if you look at what the two newspapers say about Finland, it’s still -the center right one still says, well, the Fins are doing fine, and comprehensive schooling works with them, but it wouldn’t work in Germany. And then there’s like a host of reasons. But they kind of still acknowledge that Finland is doing well. And for them it’s a model that works very well. Whereas with Asia, both newspapers say, “nope, well, this is no good”. It’s also interesting, if you look at the imagery that is used to portray -and I think in a sense, you really have to discuss the model and the anti-model in conjunction because it seems they stabilize each other. It’s like, heaven becomes much more tempting if there’s a particularly scary hell as an alternative, you know. And I’m not using these words lightly. Because if you look at how Finland is portrayed, you get these things like educational paradise to which pilgrimages are done, and so on. And so, you really get these kind of imagery of redemption. Whereas Asia, like, examination, hell, or this one quote from an article, “youth in China is like running the gauntlet from one examination to the other.” And running the gauntlet is a method of torture usually resulting in death. “Youth without sleep” is another headline I recall about South Korea. And sleep deprivation is, of course, also a method of torture. So, on the one hand, you get, “drill” is a word that comes up a lot. So, on the one hand, you’ve got this imagery of redemption and paradise. On the other hand, you’ve got the imagery of hell and torture and the barracks.

Will Brehm 23:16

And so why is Asia in quotation marks perceived, in a way, negatively whereas Finland is perceived in a more positive way?

Florian Waldow 23:27

Well, I think this has a lot to do with these prior perceptions and with the fact that countries- because we, and I mean, I completely, even as a comparative educationist here, you’re struggling to kind of get a grip of what happens in countries that, like collectively, we know so little about, other countries that we sort of mainly interpret what’s happening in the world in terms of the pre-existing stereotypes we have of the world. Stereotypes as generalizations over a group and that looking at certain countries, we kind of interpret what we’re seeing there in the light of these prior perceptions, or what we think is our prior knowledge of these countries. And that’s extremely difficult to shake. And the stereotype research has shown that these, especially hetero-stereotypes -that is stereotypes not about your own group but about a different group- are very hard to shake. And I think this is a very good example for that. That, because there is this prior perception that Asia is this place where there’s rote learning and where schools resemble barracks, that this is very hard to shake. Maybe I should add a caveat here and that’s that I’m not saying that there is no rote learning in Asia. I’m not saying that I advocate South Korea as a model to emulate or anything. That’s a different question, as it were. So, at least in my research, what I’m mainly interested in is how these references are used, and what one can say, even if one isn’t -and I certainly am not a fan of rote learning and things like that and so on- is that like people like Keita Takayama have shown that the picture would have to be much more differentiated of, again, always in “Asian education” if you wanted to kind of get a clearer grasp of the complexity and of like different things happening at different levels of schooling in Japan, for example, and so on. So, that it’s certainly not as simple, the picture, as it is usually portrayed, I think, it’s safe to say, in the German media, for example.

Will Brehm 25:12

And what do you think this says of this supposed globalized education policy field that we hear a lot about in our field?

Florian Waldow 26:07

Well, I think it’s slightly dialectical in the sense that it shows on the one hand that there actually is a globalized education policy field. References to all over the globe abound in education. But then, in a sense, the globalized education policy field has existed for a longer time than is sometimes said. Like, systems of mass schooling in Europe in the 19th century evolved, in a sense, at least in a Europeanized global policy field, if you wish. They evolved in constant mutual observation and so on. So, the globalized policy field has been around for a while. Of course, the injecting or introducing ranked knowledge about the players in this field has added a new dynamic to the whole thing. You know, like, as soon as there are ranking tables, no matter how they’re constructed, they’re going to do things to the field. I can see that in the university ranks. Wherever you see ranked knowledge. I mean, like with the introduction of the Carnegie Classification in North American universities, that kind of did things to the way the field operated. And the same thing has happened with the rise of international large-scale assessments. So, on the one hand, you can see, okay, this is a very clear indication that there is a globalized policy field whose dynamics have become intensified over recent years. On the other hand, I think we can also see that it is a field in which global knowledge is processed locally, and where local conditions shape how things like these rankings and so on, are perceived. It’s not an automatism that a PISA league table leader will become a model of the positive reference society in a country. This is not a given. It can happen. It has happened in many places. And it’s also very well possible that at some point in the future, the German perception will change there. But it’s by no means something that happens automatically. It’s something that is processed in the light of especially prior existing stereotypes and perceptions of these league leaders. So, we see a globalized policy field. But if we stay with the metaphor of the field for a while, imagine a big field that there’s going to be quite a microclimate in different places. There’s going to be sort of -some weeds will only grow in certain bits because they’ve got particularly favorable growing conditions- there will be some beautiful flowers in one corner but not the other. So, I think we should think in terms of a globalized policy field, but we should not think that this field is a homogeneous field, like with the same shade of green all over it.

Will Brehm 29:29

In about six months’ time, we’re in December of this year, the next PISA results will be announced. What are you looking for when you look at the data? What are you expecting to find?

Florian Waldow 29:42

I’m very careful about prognosis. One thing I’ve learned through observing this whole thing is to expect the unexpected. I look at some of the things that have happened in recent years I would have never thought possible. I’m sort of careful with predictions but I think what we’re probably going to see, just in terms of the results, is that the Asian countries are going to continue to dominate. Possibly dominate even more, if that is possible. When I look at how this is processed, in the German case, I think this will partly depend on where Germany ends up. And also, where Finland ends up. If the Finnish results continue to relatively decline, it will be interesting how that is processed in the German discourse- I don’t know. And also, like, I guess, if Germany continues to kind of stabilize its position somewhere near or just above the OECD average, that’s going to take some of the heat out of the debate. Like the scandalization was so particularly violent after the first rounds of PISA, because the way Germany did in PISA was sort of so divergent from the expectations. So, I think that’s going to be interesting to see. And that’s going to condition, to a large extent, what’s going to happen afterwards. Again, from a German perspective, with countries such as the UK adopting Asia as a positive reference society, it will be interesting to see if possibly via that detour as it were -by like, kind of observing other European countries that are not perceived as different as Asia, adopting the Asian model as a positive reference society -whether that might lead to a change in German perceptions. But as I said, I mean, it’s going to be very interesting to see but I’m careful to make predictions here.

Will Brehm 32:24

Well, Florian Waldow, thank you very much for joining FreshEd.

Florian Waldow 32:28

Yeah. Thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.

Coming soon.

Coming soon.