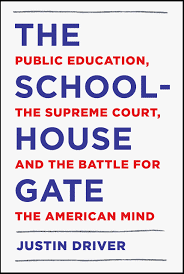

Today I continue my two-part conversation with Justin Driver, the author of the new book, The Schoolhouse Gate: Public Education, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for the American Mind.

In today’s episode, Justin recounts his biography from growing up in Washington DC to clerking for two Supreme Court justices.

Justin takes us through some of the Supreme Court cases involving public schools he thinks are most important but that receive little attention today.

He also looks to the future given the recent confirmation of Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

Justin Driver is the Harry N. Wyatt Professor of Law at the University of Chicago Law School. His book, The Schoolhouse Gate (2018 Pantheon), is receiving rave reviews. The New York Times called it “indispensable” while the Washington Post called it “masterful.”

Citation: Driver, Justin, interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 135, podcast audio, November 19, 2018. https://freshedpodcast.com/driver-p2/

Will Brehm 2:11

Justin Driver, welcome to FreshEd.

Justin Driver 2:13

Glad to be with you, Will. Thanks.

Will Brehm 2:15

Another tactic that you talk about in the sort of post-Brown era is this idea of color blindness. Can you explain how that has been used to sort of advance a particular agenda that might be counter to what Brown ruled?

Justin Driver 2:31

Yeah, so the colorblind notion of the 14th Amendment says that governmental entities are almost always prohibited from taking account of race no matter the purpose. And so Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion in Parents Involved can be seen as being about a colorblind vision of constitutional law. And of course, that vision of constitutional law has important implications for our higher education in thinking about the realm of affirmative action. And this is, you know, of course, the subject of a lawsuit that involves Harvard College right now. Interestingly, in the Parents Involved case, Justice Kennedy sort of disavowed the notion that the Equal Protection clause requires colorblindness. He voted to invalidate the programs in Louisville and Seattle because they classify individual students according to race. But he did insist that schools could take account of race, therefore not be colorblind, when they are drawing district boundaries in an effort to bring about racial integration or when they are citing schools, when they were building a new school, they can be aware of the racial demographics of the city as a whole and try to foster racial integration in that way. So, this is one area where we may see his replacement, Justice Kavanaugh, take a more conservative line in this area.

Will Brehm 4:14

So, it is quite interesting that you know, what you said at the beginning of our conversation where schools are typically the first encounter of the government for people, for young adults, for children, for citizens. But yet we see this struggle constantly of constitutional rights stopping at “the schoolhouse gate” to use the title of your book. So, what have you found to be sort of the common arguments in favor of limiting the Supreme Court’s reach into schools?

Justin Driver 4:47

Yeah, there are a host of arguments that recur in this area. Perhaps the foremost is that people say, well, Supreme Court Justices are not teachers, and they do not know what is happening in public schools. They also say that the schools are quintessentially local endeavors, and therefore the federal government should play no role whatsoever in this area. And then perhaps the other final reason would be that the Constitution of the United States does not mention education. I don’t find any of those arguments persuasive, and when one notes that all three of these arguments were advanced by the proponents of Jim Crow during the era of Brown v. Board of Education, it seems to me that we should all be less accepting of the power of those arguments. This isn’t to say that every dispute in the schoolhouse should make its way into a federal courthouse. But it does suggest that we should not just reflexively accept those arguments.

Will Brehm 6:09

So, I want to ask how you first got involved in studying education law. Where did you end up going to school in America? Like public school or private school? What is your background in schooling and legal issues in America?

Justin Driver 6:27

Yeah, so I grew up in Washington, DC. I grew up in South East Washington, DC, east of the Anacostia River. Starting from a very young age, I traveled way to upper Northwest Washington, the most privileged segment of Washington, DC, and in order to do that, I caught a bus to two different subway lines, and then had a long walk, and as I would undergo this daily trek round trip, I would think, what am I gaining as a result of this journey? Conversely, what are my neighbors not gaining? I can remember learning about Brown v. Board of Education right around 1985 and thinking that in the nation’s capital within shouting distance of the Supreme Court’s marble palace, there are still some schools that are all black, and that suggested to me that there’s often a large gap between law on the books and life on the streets. And then, when I graduated from college, I very much thought I was going to be a public-school teacher for the rest of my life. I got certified to teach public school and taught AP US history and civics to ninth graders. And when I was doing that, I had some vague sense that there were constitutional decisions that shaped the schoolhouse, but I would have been hard pressed to identify, say, Tinker v. Des Moines. And so, one of the goals that I have for this book is to render, in an accessible way, the origins of students’ constitutional rights, and the contours of students’ constitutional rights in a way that, not just lawyers but ordinary folks, including, you know, educators and principals and even enterprising high school students can understand. And so that’s sort of one of the major audiences for this book.

Will Brehm 8:28

And eventually, you end up being a clerk for two Supreme Court Justices. I think it was Justice Breyer and also Sandra Day O’Connor. Did you end up talking to them a lot about education and, you know, constitutional issues inside public schools?

Justin Driver 8:46

I did, yes. Both Justice Breyer and Justice O’Connor played no small role in motivating me to undertake this project. Not by directly encouraging me but through my interactions with them. You know, Justice O’Connor, when I was with her, was a retired Justice, and she had begun to shift her attention to thinking about the importance of civics. She was very disheartened to think about the way in which many young people don’t understand even foundational concepts of our government. And so, she was interested in trying to promote civic awareness about the separation of powers. My goal here is to do a similar sort of thing. That is to say, I believe that if students can think about their own rights, that as they exist within the schools, that it may make studying the constitution a more accessible, you know, sort of document. And so, I do hope that this will make people have greater amounts of awareness of constitutional rights generally, but if you can reach students at an impressionable age in a way that they will have a great ability to apprehend what’s going on, I think that that will lay an important foundation. Justice Breyer was also important. When I was with him, two of the cases that I write about in the book were decided, the ‘Bong Hits 4 Jesus’ case and also the ‘Parents Involved’ case. And he dedicated enormous amounts of time to thinking about both of these cases. And in doing so underscored to me the importance of constitutional decisions in schools for our nation’s larger constitutional order. You know, his father was an attorney for the school board in San Francisco, and he would often talk about how important that work was. And so, both Justice Breyer and Justice O’Connor did play, as I say, a significant role in motivating me to think about this work.

Will Brehm 10:54

Was there ever a time where you disagreed with them on some educational issue?

Justin Driver 10:59

I hold both of the Supreme Court Justices in very high esteem. I felt very lucky to be a law clerk there, and I viewed it as my job to help them with their jobs. You know, I now view the ‘Bong Hits 4 Jesus’ case in a way that is different from how Justice Breyer would have resolved it. Justice Breyer would have resolved the case along grounds of something called “qualified immunity”, and therefore not reached the underlying first amendment question. He did not go so far as to say that Joseph Frederick did not have a First Amendment right here, but he just wouldn’t have reached the question. I would have, you know, now today certainly have joined the opinion that Justice Stevens wrote, saying that punishing Joseph Frederick for this sort of speech violated his freedom of speech rights.

Will Brehm 12:00

So, returning to some of these cases and topics that your book very carefully details -both the public opinion, the Justice opinions, even the legal opinions in a lot of these journals that are published at the time- one of the topics that really stuck out to me was corporal punishment. I had absolutely no idea that this was still legal in America, let alone practiced -well, quite a lot in a few states- and more importantly that there was a clear racial difference between which students were receiving corporal punishment and which were not. And in this case, it was more African American students receiving corporal punishment. So, has the court ruled on corporal punishment, and what was some of their logic behind these rulings?

Justin Driver 12:52

Yeah, this is the issue that I care the most about that I cover in the entire book. The, in my view, scandalous persistence of corporal punishment. The Supreme Court in the 1970s had an opportunity to rein in corporal punishment in a case called Ingraham v. Wright. The case arose from truly egregious facts. James Ingraham was a middle school student in Florida, and he was on stage with some of his friends during an assembly, and he was instructed to depart the stage and did so with an insufficient sense of alacrity. For that pretty classic Middle School behavior, he was summoned to the principal’s office to receive five licks in the parlance, and that is to say, he was going to be struck with a two-foot-long wooden paddle. When his turn arose, he protested his innocence, and two assistant principals grabbed him, bent him over the principle’s desk, held down his arms and his legs, and he received not five licks but 20 licks. And this beating was so savage that even three days later he had a bruise that was six inches in diameter, that was tender, swollen, and purplish in color, and also oozing fluid. So, you would be hard-pressed to imagine a more, sort of, shocking set of facts than those that existed at Charles R. Drew Junior High School, James Ingraham’s school. It was an all-black school. And James Ingraham’s treatment was part of a larger reign of terror that existed where students were beaten for sitting in the wrong seat, for wearing the wrong socks to gym class, you know, for just incredibly minor infractions. And the school district, when they defended this policy, ended up making matters worse. There was a principal from a school in Miami Beach who said, “Oh, no, we don’t use corporal punishment in this school. We have a predominantly Jewish population, and they understand oral persuasion”. The implication there, of course, is that the black students at Charles R. Drew Junior High School understand only brute force. And so, the Supreme Court of the United States, it was a very odd opinion of five to four decision, Justice Powell said this does not qualify as punishment for constitutional purposes. The Eighth Amendment, of course, prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, but Justice Powell said, that, in effect means cruel and unusual punishment that stems from a criminal conviction. And so it was a very surprising decision because only a few years earlier, the federal courts got rid of what was called “the strap” in prison, meaning hitting inmates, and people thought, well, if you can’t hit people who have been convicted of crimes for not following orders, there’s no way in the world that you’re going to be able to hit public school students. But the Supreme Court did not see it that way and exactly as you suggest, Will, this is not just a historical artifact. Corporal punishment still exists. There are 19 states that have it, but in some ways that overstates its prevalence because there are five states that account for more than 70% of the instances of corporal punishment. And if there’s any, as I say, single goal that I have for this book, that it elevates the salience of corporal punishment and invites the Supreme Court to revisit this issue because I don’t think that the jurisdictions that retain this practice at this late date are going to abandon it on their own.

Will Brehm 16:38

And what is the constitutional issue at play for corporal punishment in your eyes?

Justin Driver 16:43

Yeah, so the strongest claim would be the Eighth Amendment claim, and I think that this is an argument that would appeal to liberals, but also the libertarian inflected vision of constitutional law that is ascendant in some right-leaning circles. If you are a libertarian, you have a skepticism of state authority. And in what instance could it be starker where the state is exercising dominion over an individual than physically hitting someone with a foreign object? I should say that public school students are the sole remaining group in American society that governmental figures can strike with impunity.

Will Brehm 17:33

Wow. I mean, that leaves me speechless. Another issue today is, and we hear it more and more from politicians, is that we need to start arming teachers to prevent lone shooters with the rise of mass shootings in American schools. What are some of the constitutional issues that you see when it comes to arming teachers, when it comes to police officers inside schools, as we see more and more of that happening. You know, what sort of issues arise constitutionally?

Justin Driver 18:08

Yeah, so the Supreme Court’s case involving the Second Amendment is a case called Heller v. District of Columbia. It’s written by Justice Scalia and did confer some limited individual’s right to bear arms, but the opinion was quite careful to say that nothing in the opinion should be understood to disturb regulations involving firearms in sensitive government buildings, and it particularly mentions public schools. So, I have seen some claims that the Second Amendment should make it so that laws prohibiting guns in public schools are impermissible. That is a very difficult argument to square with Heller itself. It is of course true that there have been a number of truly upsetting and deeply disturbing incidents involving firearms. Indeed, massacres is not too strong a word in thinking about Columbine and Newtown, and Parkland. And so, there is no doubt that many judicial opinions refer to our post-Columbine era. I am sensitive to the needs for school safety. I take that very seriously. And I do not think that if a school wishes to have metal detectors that the constitution should be understood to prohibit those efforts. I do also think at the same time that we need to have a realistic approach to the likelihood of a school shooting that’s going to happen at any particular school. I came across a statistic that suggested that any given school in America can expect a school shooting roughly once every 6000 years. And so again, it is to say that these are rare events. They are highly salient events, but we should not believe that a school shooting is a likely event where our children, say, attend schools.

Will Brehm 20:16

Another issue that seems to be on the minds of many Americans today is illegal immigration. We have Donald Trump constantly talking about this caravan of basically migrants from South America, Latin America, moving their way up through Mexico to the Mexican-American border, hoping to seek asylum from all sorts of various troubles from where they came from. In terms of immigration and unauthorized immigration, has the court ruled on anything related to immigration and education?

Justin Driver 20:54

Yeah, so there is a really important case that too few people know about called Plyler v. Doe, which was decided in the early 1980s. That case involved a Texas statute that sought to exclude unauthorized immigrants from Texas public schools. The Supreme Court of the United States invalidated that measure and said that it is unconstitutional to bar, in fact, the children of unauthorized immigrants from the nation’s public schools. Some constitutional law professors have tried to minimize the importance of that case. They say, well, Texas was the only state in the nation that had such a law at that time, and so we should not view the Supreme Court’s intervention as momentous. They say, in effect, that only those cowboys down in Texas would be drawn to this sort of a measure. But we know very well today -as your question suggests, Will- that anxieties about unauthorized immigration are far from confined to the nation’s border. And so, I view Plyler v. Doe as so significant because had the Supreme Court not in effect interred the Texas measure, there is no doubt that other states would have passed similar legislation. And so, as a result of the Plyler v. Doe decision, millions of children have been able to receive an education who otherwise would have been denied one. And so rather than viewing that as some insignificant decision of marginal import, I think that Plyler v. Doe is among the most significant decisions that Supreme Court has ever issued.

Will Brehm 22:40

I mean, obviously, it had a huge impact on access to education, which is seen as an idea that so many people in the world of education want to advance.

Justin Driver 22:51

Yeah, I should say one more thing about Plyler v. Doe, by the way, that I fear that the current court could revisit that issue. John Roberts, when he was a young attorney working in the Reagan Department of Justice, co-authored a memorandum suggesting that Plyler v. Doe was incorrectly decided. You know, Justice Kennedy, who is now no longer on the court, never weighed in expressly on Plyler v. Doe, but I strongly believe that he would have found it to be correctly decided. I could quite easily imagine his successor thinking that it was wrongly decided, and so I fear that states are going to enact legislation that is designed to invite the Supreme Court to revisit that issue, and if the court were to reverse course, that would have calamitous consequences for our constitution order.

Will Brehm 23:45

That brings up a very interesting point. Throughout your book, you really focus on the courts composition, and you focus in on these different Justices and sort of the different majority opinions that they could form, you know, 9:0 or sometimes 8:1 or sometimes 5:4. We now live with a Supreme Court that is deeply divided ideologically. But Justice Roberts is now seen as sort of the quote unquote, swing vote, which I am not sure if that even is the right way to describe it. But he said sort of in the middle ideologically. So, what do you see if you were to sort of think about the future of the Supreme Court and education? What do you see happening in terms of student constitutional rights?

Justin Driver 24:39

Yeah. So, in addition to the Plyler v. Doe decision, potentially being in flux, I can imagine a couple of other areas that Justice Kennedy’s departure and Justice Kavanaugh’s joining the court could make a difference. So, I think about the establishment clause involving religion. The Supreme Court has, in my view, done a pretty good job of making sure that public schools are not places where students are being proselytized to. When Kavanaugh was in private practice, he co-authored a brief casting doubt on some of this jurisprudence in a case called Santa Fe v. Doe, where a public school had students to deliver prayers over at a high school football game over the school’s loudspeaker. Justice Kennedy thought that did violate the establishment clause, but if Kavanaugh continues to hold the view that he expressed as an attorney, then the area of religion in public schools is a potentially hot button area. Another area that keep an eye on would be the legitimacy of race-conscious actions taken by school boards. We spoke about Parents Involved earlier, and Justice Kennedy departed from the rest of the GOP appointed Justices in finding that some race-conscious measures were permissible. Kavanaugh, when he was in private practice, wrote a piece for the Wall Street Journal, where he suggested that race-conscious measures should be almost automatically regarded as unconstitutional. And so, I think that those are two areas where the current court could lurch to the right in the area of students’ rights.

Will Brehm 26:49

So, looking across the history of Supreme Court rulings, what can we learn?

Justin Driver 26:55

One of the most important lessons that I draw from this research is that the Supreme Court has an especially vital duty to protect constitutional rights within the schools. The Court’s decision in Barnette from 1943 makes this very point in a really powerful way. That case involved requiring students to pledge allegiance to the American flag. Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that reciting the Pledge of Allegiance violated their religious faith. Justice Jackson wrote an opinion for the court that invalidated that measure, and he said that the freedom of speech involves a corollary right not to speak. But more important than any single line from that opinion is his insistence that the school is a vital theater for constitutional law, because Justice Jackson said, if we discard constitutional rights within schools, then we teach youth to discount constitutional principles as mere platitudes. And he says, we risk strangling the free mind at its source. And I cannot imagine a more powerful and important lesson than the one that Justice Jackson gave to us in the 1940s.

Will Brehm 28:24

Well, Justin Driver, thank you so much for joining FreshEd, it really was a pleasure of talking today.

Justin Driver 28:29

Thank you, Will. I really enjoyed our time together.

Constitutional Law and Public Schools, Part 2