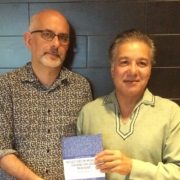

Rosalie Metro

Navigating Education and Conflict in Burma and Beyond

Today we talk about education and conflict in Burma. My guest is Rosalie Metro, an Assistant Teaching Professor in the College of Education at the University of Missouri-Columbia. As an anthropologist of education, she is interested in the conflicts that arise around history, identity, and language in the classroom. Her latest commentary in the Compare Forum argues that we need to consider the Thrid Face of Education

Rose has been researching Burma/Myanmar for the past two decades. She is the author of Histories of Burma: A Source-Based Approach to Teaching Myanmar’s History (Mote Oo, 2013), and Teaching US History Thematically: Document-Based Lessons for the Secondary Classroom (Teachers College Press, 2017). Her world history textbook will be published by Teachers College Press later this year.

Citation: Metro, Rosalie, interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 189, podcast audio, March 2, 2020. https://freshedpodcast.com/rosaliemetro/

Will Brehm 1:40

Rose Metro, welcome to FreshEd.

Rosalie Metro 1:43

Thank you.

Will Brehm 1:43

So, I want to talk a little bit today about education in conflict and post conflict societies. Supposedly there’s quite an influential book called The Two Faces of Education in Ethnic Conflict. Can you explain a little bit about what that book says and why it’s been influential in the study of conflict and education in conflict and post-conflict societies?

Rosalie Metro 2:06

Sure. So, this was a report written actually for UNICEF and edited by Kenneth Bush and Diana Saltarelli in 2000. And they broke down the potential positive impacts of education. So, how education can increase tolerance of other ethnic or linguistic groups, how educational opportunity can reduce drivers of conflict, how inclusive citizenship can be promoted, how history can be, as they put it, “disarmed”. As well as potential negative consequences. That education could be a weapon of war in the way that it’s denied to certain populations, and also in its content. So, history is often told in a way that supports a particular political point of view and causes students to hate or dislike people from other ethnic groups.

Will Brehm 2:53

These are the two faces so to speak. So, the positive face that can reduce conflict, that can create positive citizens that contribute to society. But also, a negative face that is education that is weaponized for war, or to reproduce war. And also, the content of education itself can be, quote, unquote, a bad face, a negative face.

Rosalie Metro 3:20

Exactly, yes. And I think it was an important piece because that negative face of education is often underestimated. So, maybe people hadn’t thought so much of education as a force driving conflict but only as a force that could make things better. So, I think they really did a service to the field in revealing this second face.

Will Brehm 3:41

And so how did this book, or this report, this idea that there’s two faces of education -how did it impact your own work?

Rosalie Metro 3:49

Well, when I first encountered it early in my academic career, I was really taken with it because I felt like it described a lot of what I was seeing. And so, my research is on Myanmar or Burma, and I was working with Burmese refugees in Thailand and thinking about how history textbooks produced by the military dictatorship that ruled the country from 1962 to 2010 really make ethnic conflicts worse by telling this fairy tale that Burma was a big happy family until British colonization. And then the dictatorship was carrying on this benevolent rule of the majority group, the Burmans, over all the other groups. But when ethnic minority people looked around them, they could see that their own histories were being left out. And so, some groups created their own textbooks that ended up being kind of mirror images of government textbooks in which their group were the heroes and the Burmans were the villains. But either way, these one-sided narratives really represented to me the potential of education to fuel conflict.

Will Brehm 4:55

Right. So, hence the negative face to use that term.

Rosalie Metro 4:59

Yes. Exactly.

Will Brehm 5:00

So, in your work in Burma and on the Thai border with various ethnic minorities living in Myanmar at the time, did you try and affect any change? Did you try and create a good face, a positive face, of education in that region, in that part of the world?

Rosalie Metro 5:17

I did. I did a couple of things. So, as part of my dissertation research in 2008 and 2009, I co-facilitated workshops for teachers from Burma from different ethnic backgrounds. And we talked about different versions of history and the messages that students took away from them and discussed ways to teach history in order to promote reconciliation. But what I realized was that that was much harder than I had initially thought. So, this positive face is kind of elusive. And my favorite story is that we brought teachers together to try to create a history textbook that all of them could accept, and they couldn’t even agree on a title for the book. So, we spent days on this because some ethnic minority people didn’t accept any title with Myanmar or Burma in it, and Burman people insisted on that. And it was really quite difficult. So, what we ended up doing -I mean, I kind of realized that the attempt to create one story was just doomed. And so along with a Burmese colleague named Aung Khine, I ended up creating a thematic document-based curriculum called histories of Burma, which was published by a local NGO, Mote Oo, several years back. And we collected about 100 primary source documents referencing many different groups. And our idea was that if students and teachers had access to those primary source documents, they could interpret them in many different ways instead of being told what to think by one authority or the other whether it was the government or an ethnic armed group. And that this critical thinking about history and identity could really promote that positive face of education to ameliorate conflict.

Will Brehm 7:00

So, were the themes that you decided on -were they contested?

Rosalie Metro 7:05

Well, not so much because it was just the two of us doing it. And we chose things like -we did one on British colonization and one on kind of national identity versus ethnic identity. And no. I don’t think people would disagree on the themes, nor really on what to include. I think the disagreements would come about in how people interpreted those documents.

Will Brehm 7:32

But in a sense, that was the goal that you were sort of aiming for, right? The idea that you let different groups and different people interpret the primary sources in different ways to allow for a particular discourse or conversation that might elevate or challenge people’s own ideas of history.

Rosalie Metro 7:52

Yeah, exactly. I mean, I think when you have one story in your mind about history, it’s very easy to discount the truths of other people and other groups coming from different backgrounds. And whereas if you have these documents that show that other things happened, and people had other views, you kind of have to confront those. You know, whether you agree with them or not, you have to acknowledge that they exist. And I think that that’s half the battle.

Will Brehm 8:18

Right. And so, what happened with this textbook that you helped produce?

Rosalie Metro 8:23

So, it’s in use in Burma and then also along the Thai-Burma border. It was intended for post-secondary school students, so students who are kind of between high school and college. And it’s used a lot in the private sector because they can’t use it in a government school for sure. So, all kinds of different institutions use this as a resource. I think people use it for self-study, or in ethnic areas where they have a little more freedom with what kind of curriculum to use. I think it’s been used there as well.

Will Brehm 8:58

And have you received any feedback on, has it actually begun to produce movements towards this positive face of education? It might be elusive but did this book, perhaps, make a small step in that direction?

Rosalie Metro 9:11

That’s something I haven’t really researched. So, I go back to Burma every year or so. And I often give presentations on this topic or do teacher trainings. I don’t think it’s been around long enough to really kind of measure the impact that it’s had. I would be curious to see.

Will Brehm 9:32

It sounds like a good dissertation topic for some future PhD students.

Rosalie Metro 9:35

Yeah, right.

Will Brehm 9:37

But what’s interesting in Myanmar or in Burma -you know, it’s a contested name of even the country- is that in 2010, as you said, the government changed. So, what happened with history textbooks in that country?

Rosalie Metro 9:53

Yeah. So, since 2010, various intergovernmental organizations like the Asian Development Bank, UNESCO And JICA, the Japan International Cooperation Agency have been working together with Burma’s Ministry of Education on all kinds of education and that includes rewriting the curriculum. So, so far, they’ve done Kindergarten to Grade Three textbooks and teachers’ guides. And as part of the national education strategic plan that includes goals like making education more inclusive and relevant to all students. And one big change is that whereas in the past history textbooks had been written by the Myanmar Historical Commission, which is a group of about a dozen scholars working very closely with the government, that process has opened up a bit. And I wrote about this recently in a local magazine called Frontier Myanmar and I’ll probably publish some academic papers on it as well. But yeah, very interesting process and interesting changes to the textbooks as well.

Will Brehm 10:11

So, this commission opened up, meaning that members from the public were invited in? Like who became invited into this commission?

Rosalie Metro 10:59

No, no. So, the commission still exists as it is. And there’s definitely no members of the public involved. It’s more like -so the intergovernmental organizations that are funding and sponsoring this process had input into the development of the textbooks which had not happened in the past.

Will Brehm 11:20

Okay. And so, they created some new textbooks and teachers guides, and what do they look like? How would you evaluate the content, or the two faces of education, so to speak, in this context?

Rosalie Metro 11:32

Right. So, I think we still see the negative face of education, partly because a lot of the material was just reproduced word for word from old textbooks. So, just as in the past, the heroes in social studies textbooks are almost all Burman Buddhist military leaders or kings. And that’s really alienating to groups who see those same leaders as oppressors. So, that’s definitely still the negative face. In terms of the positive face, I think there have been some changes to teaching methodology. So, for the first time, students are asked open ended questions instead of just being expected to repeat what the textbook says. And I think that that practice and coming up with your own ideas is just really crucial to questioning those meta narratives of like us versus them that can fuel conflict.

Will Brehm 11:32

Right. So, it’s a little less of a dichotomy.

Rosalie Metro 12:26

Yeah. And there are some small steps forward in terms of inclusivity. So, a Christian church in a a Pwo Karen village was shown and described in a social studies textbook, whereas in the past, only Buddhism, which is practiced by the majority was mentioned.

Will Brehm 12:41

Right. And that’s a sign that they’re trying to change some of that very Burman nationalistic elements in textbooks from before.

Rosalie Metro 12:51

Yeah, I think so.

Will Brehm 12:52

And you said that process opened up to some development agencies that were providing funding and then obviously providing some intellectual and had their own agendas in this process. Did you see any of their interests, the aid agencies, for instance, their interest finding their way into these textbooks?

Rosalie Metro 13:14

Yes. So, I think that these international organizations kind of prioritize more, the peace education mindset and toning down that Burman supremacy in textbooks. But the way that ended up being implemented is interesting. So, in the past, many stories about history involved Burman kings conquering or as the textbooks put it, “unifying” ethnic minorities, such as Hmong people. But in these new textbooks, the ethnic identifiers have been removed. So, everyone is just Myanmar, which is a word that the government uses to refer to all ethnic groups that they consider indigenous to the country in which many ethnic minority people do not accept as including them at all. And in any case, making this change, they ended up kind of making Burman supremacy invisible and erasing ethnic minorities from history. So, you don’t know anymore that that Burman king conquered the Hmong people or unified with them, or whatever. The people on both sides of those are just called Myanmar, basically, or the enemies are unnamed. And I think that these changes are really well intentioned but the way that these ideologies of peace and multiculturalism have been applied is not necessarily going to have the positive effect as intended. Hence, this sort of third face of education idea. You know, it’s mixed right? In the past, there were so few people engaged in the process of writing history textbooks, and their ideology was so clear that the negative face -or as I saw the negative face- was pretty one sided. And then what I was trying to do with Histories of Burma was a totally different approach that I, probably naively, hope can help. But these new textbooks are kind of the mixture. And I think that that really speaks to the process by which curricula are rewritten in post conflict environments. So, these days, there’s support from funders and organizations that have their own priorities, local officials are involved. And then there are local and international consultants who end up doing a lot of the work of writing these textbooks or revising them. And so, I think it’s no wonder that they end up a little bit kind of mixed up or in the middle. I mean, they’re just a lot of cooks in the kitchen there.

Will Brehm 15:29

I mean, it’s such a fascinating idea. This idea that it’s not either the positive or negative face but there’s some in-between third face that produces curriculum material that is just sort of, okay. It’s education that is both bad and good simultaneously. You know, there’s so much to sort of unpack there because it really challenges that initial book, or report that you read about education being either good or bad. And so, I guess, why is this even important? Like, I mean, is this something that we should be saying this is just how education is? Should we not be striving for that positive good face of education, and we should just sort of settle for this third face, “okay” education?

Rosalie Metro 16:15

I don’t think we should settle. I don’t think we should settle. But I think we should acknowledge it when we see it. So, I was inspired to write this Compare piece when I was at a panel at CIES 2019 on schooling in conflict and post-conflict societies and a couple of researchers on this panel cited this piece. And it’s always definitely in the back of my mind when I see panels like this. And so, some presentations really fit those extremes. So, for instance, there was one researcher from the University of Quebec, Montreal, Olivier Arvisais, and he was presenting on the Islamic State’s curriculum, which is a pretty good example of the negative face of education. It’s like, if it weren’t so horrible, it would almost be funny that the math problems are like, “Islamic State freedom fighters have 420 guns, and then they kill 200 infidels and get more, how many guns do they have now”? And there’s pictures of guns on every page. And it’s very extreme. So, we want to acknowledge that those extremes exist. But then some of the other presentations really showed more of the complexity. So, there was one by a friend of mine, Andrew Swindell, who is a grad student at UCLA, and he was looking at the implementation of mother tongue based multilingual education in Myanmar amidst this ongoing civil war, and so-called democratic transition. And he was talking about how there’s such high hopes for changes in language pedagogy, empowering ethnic minority students, and ending these decades of repression of minority languages. But when he saw this policy implemented, it was kind of more complicated. So, the goal was to have students become fluent in their mother tongue, in English, and Burmese. And people really did like being able to study in their mother tongues, but they didn’t quite end up fluent in all three languages. And so, as a result, they weren’t necessarily prepared for those higher education or professional goals they had. So, it’s like positive changes are being made but it’s not yet really addressing those structural inequalities in opportunity that drive ethnic conflict. So, when I see things like that, or there was another person on the panel, Christiana Kallon Kelly, who’s a grad student at UPenn, and she was presenting on Sierra Leone’s post-conflict curriculum. And she cited Bush and Saltarelli but at the same time, the data she was presenting is really rich and complex, and perhaps not necessarily totally captured by it. And she had a unique perspective, because she’s from Sierra Leone, and knows the context really intimately. And I was just having this feeling that, as we move toward decolonizing peace education research, and having more people from the Global South, not only applying, but also generating theories, we can kind of get at those complexities more. And we’re not just going to be presented with this negative or positive face, but more of the in-between.

Will Brehm 19:13

It seems like there’s often dichotomies that are constructed in educational research, particularly in development. You know, good or bad, public or private. It’s that very dichotomy that sort of limits our own thinking and it doesn’t allow for that complexity with which you’re talking about. And so, it’s almost like we, as in, researchers, need to overcome that pull towards viewing things in just a dichotomy between good and bad, positive and negative. Is that sort of what you’re trying to do? Is to disrupt this very dichotomy that’s common in the field of post-conflict and conflict studies?

Rosalie Metro 19:56

I think so. Yeah. And I mean, I think a lot of times when we’re drawn to those dichotomies because they’re easier to visualize and measure. And when we’re looking at a big pile of data, the extremes kind of stand out first. But we don’t have to leave it there. I mean, also, breaking down binaries is in itself, kind of a cliche, just as much as the dichotomies are. So, I’m thinking about what’s beyond that, as well. And I’m hoping that listeners will weigh in and contact me and tell me what I’m missing and what comes next. So, once we’ve broken down this binary, what comes out of that is something I’m curious about.

Will Brehm 20:38

Yeah, and certain challenges. I mean, one of the things that you said earlier that really struck me was how the new textbooks in Myanmar were, in a way, erasing ethnicity. And it was almost this sort of post ethnicity moment. And that was sort of being driven or was resulting from probably many factors, but some of it is from the aid agencies that were sort of involved in this, in the Peace Studies, as you said. They’re sort of focusing on getting beyond the ethnic identifiers as a way of sort of unifying a war-torn country. But that has serious challenges as I think you mentioned. And moving to the third face perhaps brings us to this issue of centrism and this issue of maybe being in the center is somehow post-ideological. And we’re moving beyond any of these extreme cases, and therefore, more pragmatic. But that in itself is also an ideological position and has consequences, right?

Rosalie Metro 21:43

Yes. And I think one danger is that indoctrination can become more subtle. So, in the past, in Burma, so many people just assumed that if the government said it, it was a lie because the textbooks so obviously contradicted what they saw around them. As these most obvious examples of extreme nationalism or offensive content are removed, I think the textbooks could become a more effective vehicle for propaganda or kind of marketing this idea of a nation that still isn’t inclusive but that’s at least a little easier for people to swallow.

Will Brehm 22:17

Yeah, I mean, I think that’s, that’s exactly right. I think the power of the state becomes a bit more covert, in a way, through the official curriculum then.

Rosalie Metro 22:27

Yeah, I think that’s true.

Will Brehm 22:28

But at the same time, I think one of the ideas of the third face -this notion, this concept of education that is just okay. Or in your new piece, you say, the “meh” face. The whatever. It’s okay, it’s not okay, it’s whatever- is that to me, it begins to challenge the very idea of progress, which I think many researchers in our field assume to be the case. Educational progress is, things will always get better in some linear fashion, so long as we get educated and get more people educated. Do you see any sort of challenge to this notion of progress with the meh face of education?

Rosalie Metro 23:11

I do. I mean, I think -I know- that I and I would guess that a lot of us have really ambivalent feelings about education. Like, sometimes it seems like it’s the only thing that’s going to change the world. Like, we just have to do it right. And then other times, it just seems hopelessly doomed to reinscribe oppression and just be problematic, and all these things. And I think it’s humbling to focus on mediocrity although it’s not as sexy. I think that we can admit that sometimes education just kind of supports the status quo, or is kind of okay, better than nothing, but really isn’t making things better, or making things worse, and that the middle is always moving. So, what was considered normal in the past becomes thought of as extreme and then this meh face is kind of changing as well. That it’s not a linear move toward goodness. It’s a really contested process in which what’s considered good is always changing.

Will Brehm 24:08

Yeah, I mean, that seems to be true about politics in so many countries where what is seen as the center is constantly moving in different directions and in different moments in time.

Rosalie Metro 24:20

Right. I mean, I think that’s the potential of this idea in a way that our goal might be to move the middle rather than to move the extremes. You know what I mean?

Will Brehm 24:30

Yeah, exactly. Move the center, move the meh education closer to the positive face of education.

Rosalie Metro 24:37

So, to change what’s considered normal or standard?

Will Brehm 24:40

Yeah. I mean, I keep thinking of it in terms of sort of American and British politics, where the center has really become neoliberal, where marketization of education has become something that was promoted by the Labour Party or by the Democrats and has now become sort of common, and standard, and understood as the way things should work. When in fact, it’s actually quite a radical position to assume that education should be marketized. And so, there’s this big pull now to try and change that center, to change what is assumed to be -you know, to start from the point of having private markets in education is not normal. And I think that’s the political struggle that these countries are sort of undergoing right now. And I see this similar happening in the conflict education as well, that you’re talking about in Myanmar.

Rosalie Metro 25:36

Yeah. I can see that. All of the structures that kind of support education are called into question at the same time as the curriculum is being revised. And things are kind of up in the air.

Will Brehm 25:48

So, if you were to go back to 2006 or 2007- when you were developing that textbook where you had all the disagreement with even the name of the textbook, and you settled on a thematic version of a textbook with primary sources to let people make up their own mind and their own perspectives- thinking about meh education or the third face, is there anything you would do differently today?

Rosalie Metro 26:12

I don’t think so. For better or for worse, I really can’t let go of this optimistic viewpoint that, like if people just really have the chance to look at those sources and talk with each other about them, that it will help. But I think also, you know, earlier you asked about, have I seen the effects? Like is this working? That’s where I think it’s important to really have humility. That, you know, students might take this textbook and make something completely different out of it than what I envisioned they would. And it’s such a complex process, you know. I think, as curriculum writers, or as researchers, we often think, well, if we just do this intervention, it’ll work, you know. But that takes away a lot of the agency of the people interacting with these different interventions. Like the teachers and students using these textbooks, and we really don’t know what they’re going to do with them. There’s a lot of unknowns. I don’t think I would change what I did with The Histories of Burma textbook or with the -you know, I wrote two textbooks on the same model, one for US history that was published in 2017, and another about world history that’s going to come out this or next year. And I really believe in that model. But I also think it’s not a straightforward process of just sort of making things better or making things worse. It really depends on how it’s used.

Will Brehm 27:33

Well, Rose Metro, thank you so much for joining FreshEd and keep in touch and let us know about these different books and textbooks and what the impact is in the future. It’ll be really interesting to do a cross national comparison in a way.

Rosalie Metro 27:46

Definitely. Thank you so much.

Coming soon.