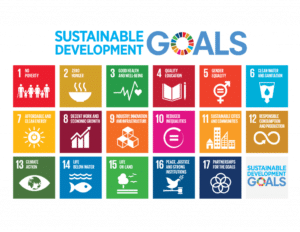

The timeframe to achieve the sustainable development goals is tight. We have just over a decade to complete the 169 targets across 17 goals. Target 4.7, which aims for all learners to acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, is particularly challenging. What are the knowledge and skills needed for sustainable development? And how can they be integrated into policies, programs, curricula, materials, and practices?

My guest today is Andy Smart, a former teacher with almost 20 years’ experience working in educational and children’s book publishing in England and Egypt. He is a co-convener of a networking initiative called Networking to Integrate SDG Target 4.7 and Social and Emotional Learning into Educational Materials, or NISSEM for short, where he is interested in how textbooks support pro-social learning in low- and middle-income countries. Together with Margaret Sinclair, Aaron Benavot, Jean Bernard, Colette Chabbot, S. Garnett Russell, and James Williams, Andy has recently co-edited a volume entitled NISSEM Global Briefs: Educating for the Social, the Emotional, and the Sustainable. This collection aims at helping education ministries, donors, consultancy groups and NGOs advance SDG target 4.7 in low-and middle-income countries.

Photo by: Helena g Anderson

Citation: Smart, Andy, interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 182, podcast audio, November 25, 2019. https://freshedpodcast.com/andysmart/

Will Brehm 3:03

Andy Smart, welcome to FreshEd.

Andy Smart 3:05

Thanks, Will. It is a great pleasure to be here.

Will Brehm 3:07

Okay, so, I want to start with a pretty subjective question, let’s say. Do you think the Sustainable Development Goals will actually be achieved by 2030?

Andy Smart 3:17

Well, I wish I had the answer to that one. I wish everybody else had the answer to that one. I am naturally an optimist by nature, but I recognize these are hugely ambitious across the board. I mean, you know, targets that talk about, you know, ensuring that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary, secondary education. I mean, the word “all” is a pretty big word. Even goals like ending poverty. Yeah, I wish. So, these are hugely ambitious. And, I was interested to see, just these past few days, how there’s been some discussion over the announcement by the Bank of their ending learning poverty initiative, which is setting what might be called a more realistic target. Of course, that’s been getting a bit of pushback as to, you know, why dropping back from the ambitions of the Sustainable Development Goals? So, you know, you travel hopefully, basically, in this business; you arrive as far as you can.

Will Brehm 4:19

So, you brought up the World Bank’s annual meeting where they introduced this idea of “learning poverty”, some metric to measure learning poverty. This particular show that we’re recording now is not about that topic, even though it probably deserves a whole show unto itself, but you said it is sort of trying to make, maybe a more, a metric that could be achieved. So, what is problematic about the SDGs as they’re currently written, in terms of being able to achieve them by 2030, that has made the World Bank propose something maybe less ambitious and perhaps more feasible?

Andy Smart 4:55

Yeah, I mean this is way above my pay grade, as we might say, but I mean, my view on any kind of system change, which I think is what we’re engaged in within the NISSEM team: we’re looking at system changes which are scalable and sustainable. But you know, systemic change across a country, it means changing the practices of thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, of people. When we are looking at how textbooks impact on classroom practices, we are talking about teachers’ practices. We are talking about all those who support the teachers: the supervisors, head teachers, etc. We are talking about a lot of people changing the way they do things. That is at bottom why I would be cautious about how far you can get within this quite short time.

Will Brehm 5:52

So, in these new policy briefs that you and your colleagues put together and put out as part of NISSEM, you talk about how SDG Target 4.7 is sort of very critical to the SDG 4 overall, if not all of the SDGs. What is SDG Target 4.7, briefly?

Andy Smart 6:13

Well, the shorthand that we tend to use within the NISSEM networking team is the pro-social themes and values. So it’s looking at a more holistic view of the purpose of education, and it’s bringing together some of the stories that have been going on in the education and development arena for decades and trying to group them together in a single package. Of course, it’s very diverse; it seems rather sort of unbalanced, sometimes not very clear. On the other hand, I would say you could juxtapose what you find in 4.7 as being the other side of education: you’ve got the academic purpose, and you’ve got the non-academic purpose. And I think that’s something which resonates for people, both in the practitioner community, but also in terms of parents and students themselves, you know, that is the reason kids go to school, why parents send the kids to school. It is partly, of course, about getting those academic skills and qualifications, but it’s also about a lot more than that. And that’s what 4.7 brings together. It’s the pro-social aspects of education.

Will Brehm 7:33

And so, what would be some of these themes in this pro-social aspect of education, or these non-academic areas? How would we start to classify what some of these themes would be?

Andy Smart 7:43

Well, I mean, you could start with the name of the Sustainable Development Goals itself. So “sustainability” is a clear theme that needs to be unpacked in all sorts of ways. So, sustainability is not simply about environmental protection; it is about sustainability across social fabrics and other aspects. It is also about gender equality; it is about cohesion between communities. A lot of the schools that we are targeting in the low and middle-income countries and post-conflict countries – which are the areas of interest for us in the NISSEM networking group – these are countries which are challenged by social tensions within the country, as well as refugee tensions, etc. So, you know, social cohesion is clearly an important theme, and promotion of peace and resolution conflict.

Will Brehm 8:38

So, these different themes: the social fabric, the gender equality, social cohesion, peace, and reconciliation, even the environment. In the policy brief, the term that is often used is this idea of “social and emotional learning”. You know, I hear that as just jargon, and quite vague and very difficult to even begin to comprehend and define. What is social and emotional learning? And why is it important in the education of young adults and young children?

Andy Smart 9:08

Well, first, I want to thank you for your honesty, Will. To admit confusion, I think, is a great starting point for any understanding. I think everybody has their different understandings. And that’s part of the challenge that we face. To some extent, this is due to the terminologies that are used, many of which overlap, and you will find any discussion or any text that is addressing these issues, especially within the non-OECD country context, has to start out by saying, “Well, we’ve got all these terms. How do they overlap? How do we separate them out? What do they mean in these different contexts?” So that’s going to lead to confusion, that’s for sure. Where there is a common understanding, I think, and that’s what brought us together within the NISSEM team, is that although we come from different backgrounds, we all had this sense that what we were doing needed to be rooted in something that was not part of the narrow academic purpose of education, but it was rooted in what we understand to be the meaning of the word “learning” itself. And so, learning, in my view, is often used as shorthand for “learning outcomes”, and learning outcomes is a shorthand for “academic achievements”. But I think it’s critical that we think of learning as a process, not just as an outcome. And so, “social and emotional learning” describes, actually, how learning happens, as well as the purpose of learning. So, this begins to take us into something which is, I think, very important, very interesting, but also quite difficult to grasp unless you have a lot of time to unpack it in different ways. But separating, to some extent, the idea of the process of learning from the product or the outcomes of learning, I think, is very important.

Will Brehm 11:08

So, I mean, it almost sounds like it is a philosophical issue here. The purpose of learning, I would imagine there is not one universal purpose of learning; that it would be contextualized both within nation-states, within governments, but also within households. You know, families probably have very different conceptions of the purpose of learning.

Andy Smart 11:30

Absolutely. I mean, there is increasing evidence for how the social and the emotional play a part in learning, not only in academic learning outcomes but also in building the more rounded learner and rounded member of society. So, a lot of this research is coming out of higher-income contexts because that’s where research is better funded. But one of the things we’re trying to do is apply the appropriate evidence and results of this research into other contexts. But at bottom, there are some universal principles, or universal ideas, about how learning happens. After all, the child, who age seven in one country, has pretty much similar developmental processes as a child age seven in another country. And as far as I’m concerned, I think that the differences between contexts are more related to the differences in the way the adults operate around the child than in the way the child is actually following their own developmental path.

Will Brehm 12:41

So, what would be some of these universal principles, then, of social and emotional learning?

Andy Smart 12:47

Yeah, that’s where you get into the wonderful world of models. And so, we love models. We all love models. They have sort of visual directness that is immediately appealing. Unless they’re far too complicated, which some of them are. But there are definitely various models, and it’s not too difficult to bring them together and compare them. And again, when commentators or practitioners are looking at the different models, you have to start thinking, “So, what are the common characteristics of these models? And then how do they apply in my own context?” The best-known model of all – or the most widely quoted, let’s say – is the one that comes out of Chicago: the CASEL model, with these five competencies. Again, the word “competency” itself is a word that needs a bit of thought. But they have these five competencies, which are: the two related to the self, or the intrapersonal, which has the self-awareness and the self-management; and then the interpersonal, the relations between people. That is the social awareness and the relationship skills. And then the fifth competency is responsible decision making. That is one of the models, and there are several around. They tend to be simplifying because that has to be the nature of a model; otherwise, it’s going to be difficult to grasp. And sometimes you might think, “Well, this is a bit too simplistic”. So, I think that has to be a balance between what these models try to do in terms of simplifying and what they have to do in terms of recognizing the complexity of what we’re talking about.

Will Brehm 14:31

Another idea in the NISSEM policy brief is about this idea of 21st-century skills. And I’ll admit that this also causes some confusion for me, because it’s rather vague, and you know, why are we talking 21st-century skills rather than 20th-century skills? Are these skills that people in the 20th century, in the 19th century never needed? Why aren’t we talking about the 22nd-century skills? So, what on earth is that idea? How do we begin to understand 21st-century skills?

Andy Smart 15:03

Yeah, I think probably – I haven’t done a sort of word count on this – but I think in the NISSEM global briefs, you probably won’t find so many references to 21st-century skills, at least not necessarily from within the co-editors. It is not a term that we have used a great deal. I think different contexts have different preferences for the way they think about these, what may be called sometimes “soft skills”, what may be called “21st-century skills”. What we prefer, as a way of thinking, to call “social and emotional learning”. I would say my personal view is that very often, when people are talking about 21st-century skills, first of all, they’re talking about, to some extent, vocational or pro-career, pro-work kind of soft skills, and therefore it’s not something which is as much used in terms of primary education as for secondary and post-secondary education. So, I would say the opposite of a 21st-century skill might be the traditional academic skills. To some extent, we are back to what we were talking about at the beginning of this conversation. It is about thinking about these different skills areas and different purposes of education. Some of that comes from studies about what employers are looking for: they’re not just looking for the hard skills, sometimes people rather disparaging call “the basics” – the reading, writing, and so on. But the employers are talking about they need these “people skills”, these 21st-century skills. But again, those are very often coming from higher-income environments, which are not our main area of focus.

Will Brehm 16:45

So, let’s turn to some examples here, right. So, SDG Target 4.7 has this non-academic focus of social and emotional learning, maybe 21st century skills or soft skills, all these other non-academic skills that are valuable and important to the learning process. Now, what does that actually look like in practice? In non-rich countries, what have you found? Can you give some examples of, you know, what even exists today?

Andy Smart 17:17

Yeah, before I answer that, what I wanted to just underline is that we are not promoting the idea that non-academic skills are any way more important than the academic skills. So, I think the big message from the research, and the message that we carry, is that the two are interrelated and impossible to disconnect. And I think this is something which the neuroscience is very much telling us, and particularly the researcher who we interviewed for the NISSEM global briefs, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang at University of Southern California. So, this is really about how social and emotional learning in the field of cognitive science and neuroscience supports academic learning, and you cannot separate the two out. So that is the first thing I want to say. So, going back to the examples, well, I mean the examples that we are looking at primarily, as you know, are the lower-middle-income countries. And the reason we are focusing on that is partly because that’s where we’ve always worked all our lives. That is where I started out as a teacher, in low-income countries, in government schools. And the reason that what we’re promoting as a sort of NISSEM approach is that there are characteristics across low- and middle-income countries that make them slightly different from contexts of high-income countries. One of the differences is the way that the curriculum operates. What is called a curriculum in a school in, say, the UK or the US, is very often something that belongs to the school. You have national curriculum standards or state standards, and then the school develops a curriculum within that sort of framework. Now, in low- and middle-income countries, that’s different. The curriculum is what comes down from government, from the Ministry of Education. And very often, it’s what’s represented in the textbook. So, that’s why we see the textbook as so critical to this whole business: because the textbook shapes so much of what happens in the classroom in terms of the teaching, learning and the activities, and the way of thinking, and the pedagogy. So that’s something which is really characteristic of the lower-middle-income countries. And it is why we are focusing on textbooks as a main vehicle for the NISSEM ideas. Now, there’s a paper in the NISSEM global briefs which comes out of my own experience working with the National Curriculum Textbook Board in Bangladesh a few years ago, where we were asked to work with the curriculum developers who were, to some extent, also the textbook writers. And all the textbooks in Bangladesh are centrally written by the NCTB, National Curriculum Textbook Board. All schools use the same textbooks. And we were asked to come in and look at how the textbooks shape what happens in the classroom to improve learning outcomes. So, this was funded by cross donor, sectoral approach and the paper that’s in the global briefs talks about what we were able to do in terms of the social studies for upper primary, and to set out a different kind of way of teaching and learning in the classroom what we and others have called a “structured pedagogy”, which is not scripting a kind of step-by-step, this is what you should do as a teacher and reducing the teacher’s autonomy to very narrow area, but setting out a principle for teaching and learning that will work in a crowded classroom, limited number of resources and doesn’t push the teacher into something which is an imported kind of over child-centered pedagogy, but it’s something that takes them into something which is supported by social and emotional learning principles, but within an academic framework to achieve better learning outcomes, more engagement by learners, and frankly, more engagement by teachers. And we’ve had some great feedback from the teachers who have used these books in Bangladesh.

Will Brehm 21:16

So, I would imagine this then, you know, not only changing textbooks in a particular way, but I would imagine the preparation of teachers and how to be a teacher, teacher training, in a sense, would similarly have to change to incorporate these social and emotional learning.

Andy Smart 21:36

Yes, absolutely. And I don’t want to oversell the power of the textbook to create change. I mean, after all, the tool is as good as what you do with it. But what we see the textbook as is a sort of lever for change; it enables different way of thinking, a different way of supporting good pedagogy that can be translated into teacher education, into the professional development, even into the assessment approach. But the textbooks legitimize approaches. I think this is a critical point about the role that textbooks play. There is a textbook in every classroom, and many cases in every home in the country. In a large country like Bangladesh, there is a lot of, sort of policy statements and legitimization statements going on. And what we found was that the textbooks that were in use beforehand were really gearing the teacher to teach by rote learning. In fact, there was really no other recourse for the teacher other than to teach by rote learning, for various reasons. Partly, because the language was very dense, very academic. Too many concepts piled onto the page, partly coming out of the curriculum itself. And then a textbook writing plan that is based on what I would simply call, you know, “comprehension plus”. So, you have a great chunk of text. It could be two, three pages of text, uninterrupted text, followed by some very narrow gap-filling, you know, right-or-wrong type answers. And that’s the way that science was taught in terms of the textbook. It’s always social studies, very often language. So, the core subjects are being taught in this sort of comprehension plus kind of way. And I would say by comprehension, we’re talking about a narrow definition comprehension; we’re talking about comprehension where there is only a right or wrong answer. So, what we tried to do is just rethink that text in the textbook so that it is supporting a pedagogy. So that when you open the textbook as a teacher, you can see how this could be taught. And this is how teachers across the world, in contexts where they have a chance to choose their textbooks, that’s how they evaluate a textbook. They pick up a textbook; they open it up and say, “Oh yeah, I can see how this would work in the classroom”. And they’re not only looking at the language level and the quality of illustrations, but they’re looking at how the learning will flow out of the way it’s presented in the materials. So that is what we’re trying to do in an appropriate way for the context that we’re working in.

Will Brehm 24:17

And have you found any challenges? I mean it seems like, you know, here’s a group of foreign experts coming into a country and saying, “Based on these globally circulating policies and ideas, this is the more appropriate way to design a textbook, or have teachers’ pedagogy implemented in a classroom. So, in a sense, there must be challenges. It must be deeply political since education is a deeply political process, particularly at the national level. And if textbooks are being centrally created, even more so. So, I just wonder: have governments been open and receptive to some of these ideas that have been sort of externally brought into some of these countries?

Andy Smart 25:05

So, I think that’s a really important question, Will. And people working in this sector need to proceed with humility. We need to recognize that we’re coming from outside. We don’t bring answers; we bring different ways of thinking. And we proceed through partnership, collaboration, discussion, etc. On the other hand, I would say that even if we might talk about something that looks like the global North on the one hand, the global South on the other hand, each of those communities represents a wide range of different perspectives. So, when we are talking to partners in government, there are going to be people with very different ideas. There are going to be policymakers; there are going to be curriculum directors; there are going to be curriculum writers, textbook writers, teachers. There are not going to be teachers in urban areas and rural areas who are going to have quite different ways of thinking and doing things. So, we have to reflect, as far as possible, a huge range of perspectives and needs. I’ll give an example: So, sometimes, you know, I’m sitting in the office of a curriculum directorate in a particular low-middle income country, and looking at what role experienced teachers are playing in the process of contributing to textbook development, or textbook evaluation so that the materials that are being provided actually are fit for purpose and they’ve been designed with teachers’ needs in mind. And quite often, you get a bit of pushback in those curriculum directorates because they’re often quite senior people, they’ve had strong academic backgrounds, they’re in very comfortable government jobs. And they’re not thinking necessarily about how the teacher in the rural areas thinks about things, and they’re not necessarily valuing how those teachers in rural areas think about things, and maybe just don’t trust the teachers to make good decisions; they don’t trust the teachers’ judgments. And I think that’s part of the issue. So I think, yes, we need to be humble about what we define as our own expertise and experience, but we also need to ensure that the different voices are brought into that conversation at every point, and not just at the sort of high level, policy discussion level. You know, at every point in the chain, which takes us into the classroom in the rural and semi-rural areas of the country.

Will Brehm 27:25

I guess, you know, this idea that there’s all these different voices, and there’s sort of this political process that goes into the creation, the reform of textbooks, of teacher training, of all different aspects of the education system, it would also necessarily mean that the measurement of these, you know, outcomes of academic and non-academic skills would sort of go through this same political process, and then therefore be different in each country. And then the question that I have then is: How then do you begin to think about measurement of social and emotional learning on a global level that is comparable if these measurement indicators are being sort of debated within each nation with a different set of politic?

Andy Smart 28:08

Yeah, I think that is fundamental. And that for us is a really testing question within NISSEM, because to some extent, we are really still trying to develop what you might call “proof of concept”. And by “proof”, we normally expect to see evidence, not just sort of argumentation. So, evidence and measurements, I think we need to think about it in different ways. So, what some people expect from measurement is something more related to accountability. What other people expect from measurement is more related to evidence that you can build on in order to improve what you’re doing. So, I think this takes us back to, to some extent, the way that measurement and assessment are used in classrooms. You know, there is the idea of summative and formative assessment, and I think when we’re thinking about measurement of the impact of social emotional learning, we have to think about it, to some extent, in that same sort of way. So, measurement for learning how to do things better as planners, as policymakers, as curriculum specialists. Yes, I think it’s very possible to create a system for measuring something that is culturally, rather, let’s say, contextualized, but conforms to good practices in terms of reliability and validity, and is a combination of different measurement instruments. So, to some extent, observation. To some extent, self-reporting. To some extent, testing. So, I think that’s all very possible because that’s intensive and quite expensive, and has to be done on a sampling basis. Then, the other kind of measurement, which sometimes what comes to mind in some discussions, is measurements as system-wide accountability, and being treated in the same way that academic learning outcomes would be measured, which, you know, allows you to say whether the system as a whole is benefiting from the inputs that you’re providing. And I think that’s more problematic, and I think that takes us back a little bit to what we were saying earlier, which is the relationship between academic learning and social emotional learning. That the social emotional learning supports the academic learning, but at the same time, it has its own clear validity. It is not there simply to provide a platform for academic learning, that it has its own purpose, that’s part of the purpose of education. And so when we’re measuring the academic outcomes, to some extent, we’re measuring the impact of the social emotional learning, but at the same time, for us at least in NISSEM, we would like to be able to do more to show proof of concept, and to show through more intensive, more diverse measuring processes and instruments, that providing social emotional learning inputs really can make a difference. Not only to the academic learning outcomes but also to long-term engagement with learning, to produce lifelong learners, not learners who are simply able to pass the end-of-month or end-of-term or end-of-year exams.

Will Brehm 31:32

And do you think this will all be possible in the next ten years?

Andy Smart 31:35

Define “this”, Will.

Will Brehm 31:39

I guess, you know, what NISSEM is sort of, you know, this proof of concept is step one, but obviously, moving forward is that there would be some system-level reforms happening in line with SDG 4.7. And, you know, the goals are concluding in 2030. You know, it doesn’t seem like that long for the type and extent of change that is being discussed.

Andy Smart 32:05

Yes. Huge challenge. What I would say is this: that we sense that there is an enormous receptivity to these ideas at the level of policy strategy, both in the global North and, as far as we can see, in the global South. We were encouraged by the responses that we were getting in presenting the global briefs at the World Bank and the Global Partnership for Education recently. So, to some extent, that part, we feel that there is an acknowledgement these are important issues that could make a difference. How do we turn this into a proof of concept? How do we embed what we want to do in the textbooks and curricula of the countries that we are concerned about? I guess “One by one” is the answer to that. So, what we are looking to do is to show, in small number of countries, that here is a different way of doing things. Here is some of the evidence that shows it appears to be working – obviously, the timescale is very short. And then to expand from there. If we were able to achieve a number of changes in terms of textbooks and curriculum in a large number of countries within the next ten years, and the momentum is clearly moving in the right direction, and those who have adopted this approach are able to show that is making a difference to them, and to impress those who have not yet adopted the approach, I would say that would be tremendous progress. And obviously, our part is just a tiny part in the overall drive to achieve as much as possible under the SDGs in this very short time.

Will Brehm 33:59

Well, Andy Smart, thank you so much for joining FreshEd. It really was a pleasure of talking today.

Andy Smart 34:03

Will, the pleasure was all mine. I really enjoyed that. Thank you.

Advancing SDG Target 4.7

Is America addicted to education reform? My guest today,

Is America addicted to education reform? My guest today,