What’s the relationship between test scores and gross domestic product? Do higher test scores lead to higher GDP?

This question may seem a bit strange because most people think about the value of education on a much smaller, less abstract scale, usually in terms of “my children” or “my education.” Will my children earn a higher wage in the future if they do well on school examinations today? If I major in engineering, will I earn a higher income than if I majored in English?

The answer to these question is usually assumed to be a resounding “yes.” Doing better on examinations or studying subjects that are perceived to be more valuable will result in higher wages at the individual level and higher GDP at the national level. Such a belief shapes educational policies and influences educational decision making by families. It has even resulted in a global private tutoring industry that prepares students for tests in hopes of getting ahead.

But what if this assumption isn’t true? What if the relationship between test scores and GDP isn’t so straightforward?

With me today are Hikaru Komatsu and Jeremy Rappleye. Recently they have been publishing numerous articles (see here, here, and here) challenging the statistical research supporting the conclusion that higher tests scores cause higher GDPs. Instead, they find that test scores don’t determine GDP by all that much.

Hikaru Komatsu and Jeremy Rappleye are based at the Graduate School of Education at Kyoto University. Their most recent op-ed appeared in the Washington Post.

Citation: Komatsu, Hikaro and Rappleye, Jeremy, interview with Will Brehm, FreshEd, 71, podcast audio. May 1, 2017.

Will Brehm: 2:12

Hikaru Komatsu and Jeremy Rappleye, welcome to FreshEd.

Hikaru Komatsu: 2:16

Thanks for having us.

Jeremy Rappleye: 2:18

Thank you, Will. Before we begin, let me just say how much I really enjoy your show. And I learned so much from it. And I really applaud you for creating this space and doing such high quality shows week in and week out. So thank you very much for having us.

Will Brehm: 2:30

Thanks for the kind words. You, two have been doing quite a lot of work lately on really challenging some commonplace assumptions between test scores and GDP – gross domestic product. What is the normal relationship many researchers have between test scores? What students know and gross domestic product? How much a country is growing or how much it’s worth?

Jeremy Rappleye: 2:59

Yeah, thanks, Will. I’ll take the first question here, I would say that the common understanding of the relationship between test scores and gross domestic project is the higher your test scores, the greater your future GDP. This is the claim at its most simple and if we try to be more specific, the understanding is that the higher people test scores in a particular population in fields that are, say relevant for economic growth, the higher GDP will be in the future. So relevant fields here are most likely to be defined as math and science or math and science scores, and also language to a certain extent in particular reading. So the exact fields that international learning assessments such as PISA measure, and in that sense, we can also be more specific about the type of economic model embedded in this common understanding. Specifically, it is one that envisions an economy growing as a result of technological progress. That is, the more technological innovation and the accumulation of knowledge, the higher economic growth rates will be in the future.

Will Brehm: 4:02

And what sort of evidence exists, like do researchers have data, empirical data that shows that this relationship is correct, that higher test scores will equate to higher GDP in the future?

Jeremy Rappleye: 4:19

Yes. So in particular, in the last, let’s say, 10 years, the empirical research base for these claims has become very strong in some circles. Now, try to be specific here, the evidence for this common understanding in its current form, I believe, comes from, primarily from two researchers: one is Eric Hanushek at Stanford University and Ludger Woessmann. I apologize, I probably don’t pronounce the name right, based at Munich University. And I think Eric Hanushek appeared on FreshEd quite recently, if I’m not mistaken. In any case, their work constructs roughly a 40 year history of test scores, and matches that with 40 years of economic growth worldwide. So roughly from the 1960s to the year 2000. And when they say worldwide, they actually mean about 60 countries globally, mostly the high income countries that have participated in international assessments, international achievement tests consistently over that period. So to be more specific, their 40 year history of test scores combines data from two international comparative tests: the IEA-SIMS and TIMSS studies and the OECD’s recent PISA studies. So for GDP, they use a standard Penn World Table data set and listeners who are interested can find kind of full details of this in our paper. But I think the point here is that when Hanushek and Woessmann look at the longitudinal relationship between test scores and GDP growth, they find a very strong correlation. That means that across 60 countries, the higher test score outcomes were, the higher GDP growth was, and I think Hikaro might talk about this in more detail, the difference, particularly between the idea of association and causality.

But the point I want to make here is that it’s been so strong, these empirical claims have been so strong, that’s given a lot of momentum to the idea that there’s this strong empirical basis for the linkage between test scores and GDP. And I think that the work of Hanushek and Woessmann is spelled out in many places, as maybe I’ll discuss later in the interview. But the most comprehensive treatment is found in a book entitled “The Knowledge Capital of Nations – Education and the Economics of Growth”, which was published in the year 2015.

Will Brehm: 6:43

So you said that there’s a strong correlation, but is this the relationship between test scores and GDP causal? And I mean, maybe this is a little getting into some of the more technical statistical language here might be useful, to try and understand this claim.

Jeremy Rappleye: 7:02

Yes. So it’s a very good point. And it’s very important to understand the difference between an association or correlation and causality, I think we probably are betters to wait for Hikaro’s discussion of this. But let me kind of lead into that by giving you two quotes where Hanushek and Woessmann really make the claim that the relationship is causal, not just the correlation. So the first quote and this is this kind of crystallizes or kind of encapsulates the whole findings from their body of work, and they say, quote, “with respect to magnitude, one standard deviation in test scores measured at the OECD student level is associated with an average annual growth rate in GDP per capita, two percentage points higher over the 40 years that we observed.” Now, in that quote, they use the word association, as many of the listeners will have heard. But elsewhere, they talk and talk repeatedly about causality. So here’s the second quote, they say, “our earlier research shows the causal relationship between a nation skills its economic capital, and its long run growth rate, making it possible to estimate how education policies affect each nation’s expected economic performance.” So in simple terms, if you can boost test scores, you will achieve higher GDP growth. And this certainty comes out of the idea that the relationship is indeed causal.

Will Brehm: 8:38

That level of certainty, obviously, must impact education policymakers, right to know that if you increase scores as measured on PISA or TIMSS, you will achieve greater economic growth. I mean, it seems like it makes the lives of policymakers a lot easier.

Jeremy Rappleye: 8:55

Absolutely Will, we believe that the attraction, both the attraction of this claim, and the impact of this claim is growing. And through these types of studies, policymakers who previously had to deal with a very complex equation around education are led to believe that the data shows that an aggressive reform policy that increases test scores will, say, 20 or 30 years in the future, lead to major, quite major economic gains. And if I can give you just another quote, and I apologize for the quotes, but I don’t want you to think I’m misphrasing or summarizing the work of Eric Hanushek and Woessmann, but this quote that of their shows the types of kind of spectacular education gains or economic gains that policies can expect to achieve if they implement this kind of policies directed towards raising test scores. So here, I quote, “for lower middle income countries, future gains would be 13 times current GDP and an average out to a 28% higher GDP over the next 80 years. And for upper middle income countries, it would average out to a 16% higher GDP” unquote. So now, Will, if you are a policymaker, you wouldn’t want to forfeit these games, would you? So this research becomes really a motivation for policymakers putting a much greater emphasis on not just math and science, but on cognitive test scores across the board.

But there’s a fascinating bit here, I want to highlight and maybe we want to unpack it later on in the interview. But you might expect that this kind of narrowing the focus of education around test scores would create a lot of resistance. But actually, the GDP gains of increasing test scores that Hanushek and Woessmann project is actually so great that it is projected to pay for everything in education. So it’s not really a choice between alternatives. But instead of a sure-win policy versus kind of more of the same policy, uncertainty, ambiguity, complexity that we’ve seen in the past.

And sorry, this is a long answer, Will. But I would just really want to emphasize, if we talk about how these academic research claims are finding their way into policy or impacting policy, we have to talk about two organizations that have really latched onto these views, and are advocating them strongly to policymakers worldwide. And the first is the World Bank who hired Hanushek and Woessmann to connect their academic findings to policymaking for low income countries. And this report was published by the World Bank as education quality and economic growth as the title “Education Quality and Economic Growth” was published in 2007. And the second organization that has been really at the forefront here is the OECD, they also hired Hanushek and Woessmann to share their findings and discuss the policy implications. And this report was entitled, “Universal Basic Skills: What Countries Stand to Gain” and that was published in 2015. So maybe towards the end of the interview, after we discuss our study, we can return to discuss how these organizations are really central to making that empirical work into concrete policy recommendations.

Will Brehm: 12:13

So what sort of problems do you find with Hanushek and Woessmann analysis of the relationship between test scores and GDP?

Hikaru Komatsu: 12:23

Okay, the problem we found is temporal mismatch that is Professor Hanushek used an inappropriate period for economic growth. That is Professor Hanushek compare test scores recorded during 1960 to 2000 with economic growth for the same period. But this is a little bit strange. Why, because it takes at least several decades for students to become adults and occupy a major portion of workforce. So from our perspective, test scores for given period should be compared with economic growth in subsequent periods. This is the problem we found.

Will Brehm: 13:17

So for instance, it would be like the test scores from 1960 should be connected to the economic growth rate of say, the 1970s there needs to be some sort of gap between the two, is that correct?

Hikaru Komatsu: 13:31

That’s correct.

Will Brehm: 13:31

Okay. So then in your study, I mean, did you do this and what did you find?

Hikaru Komatsu: 13:36

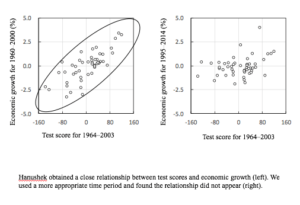

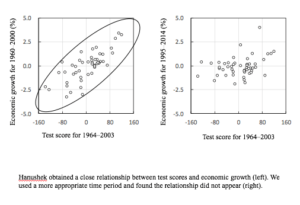

We did this, our study is very simple. We compare test scores for 1960 to 2000, which is exactly the data used by Professor Hanushek. We compare this data with economic growth in subsequent periods such as 1980 to 2000 or 1990 to 2010 or something like that. And we found that the relationship between test scores and economic growth were much much weaker than that reported by Professor Hanushek. Probably audience would see figure in the web, in the website of FreshEd, and there would be two figures, left one is the original one reported by Professor Hanushek. And there is a strong relationship between economic growth and test scores. While the right one is that we found and the relationship is very unclear. So let me explain how we that relationship is when test score for 1960 to 2000 was compared with economic growth. For 1995 to 2014, only 10% of the variation in economic growth among countries was explained by the variation in test scores. That is, the remaining 90% of the variation in economic growth should be responsible for other factors. This means that it is totally unreasonable to use test scores as the only factor to predict future economic growth. And this is what Professor Hanushek did in his study and policy recommendations.

Will Brehm: 15:40

So in your study, you found that 10% of the variation of GDP can be explained by the variation of test scores. What percentage did Hanushek and Woessmann’s study uncover?

Hikaru Komatsu: 15:53

Probably their percentage was around 70 and we try to replicate Professor Hanushek’s finding, in our case, the percentage was 57 or so and the difference between 57, 70 would be caused by the difference in the version of the data we used. In order to extend that time period, we used an updated version of that data, that data set is exactly the same, but the difference is only the version.

Will Brehm: 16:28

So a difference between 50% and 70% is pretty minimal. But the difference between 10% and 70% is enough to question the basically the conclusions that are drawn from that data.

Hikaru Komatsu: 16:42

Yeah, right. If that relationship originally reported by Professor Hanushek is causal, we should have found that comparably strong relationship between test scores for a given period and economic growth for subsequence periods. But we found very weak relationship so it suggests that that relationship originally reported by Professor Hanushek does not always represent the causal relationship. This is our point.

Will Brehm: 17:17

It seems like this is a very profound point that could be rather earth shattering for many people’s assumptions about education and its value for economic growth.

Jeremy Rappleye: 17:31

Thanks, Will, I’d like to fill in a little bit pick up on what Komatsu sensei was arguing there. One of the important points to understand about this 70% of the variation is explained by test scores, the strength of that correlation leads to very strong policy recommendations. So, I’m going to try to unpack a little bit of what I said earlier, because I think it’s an important point, I’ll try to do it academically first, and then I will try to give a simple version that will be a lot easier for listeners to understand.

But basically, if you have a correlation causality link that strongly then Hanushek and Woessmann are claiming that you can first increase your test scores, and it will produce so much excessive growth in the future, that you can redirect that excessive growth back into all other types of educational goods that you need. So in terms of equity, in terms of inclusiveness, you could even redirect that much extra money into healthcare, to sustainability goals, all of these things. So as we both know, these are two sides of the camp is education for economic growth, or is it for equities, is it for inclusiveness, is it personal development. These are the types of debates that have always been with education as an academic study, but he’s able to transcend, they are able to transcend that debate based on the strong causal claims, though, just to fill that in academically. So the claim is that if 3.5% of GDP is spent for education, this is from the World Bank report in 2007. But if over 20 or 30 years, you could increase your test scores by point five standard deviation, it would lead to 5% higher GDP on average, and quote, “this gross dividend would more than cover all the primary and secondary schools spending.” What that means is if you focus on raising cognitive levels, test scores, you could get enough growth that you would ultimately get more money for education for whatever types of educational goals you want to pursue. In the 2015 OECD report Hanushek and Woessmann write that quote “the economic benefit of cognitive gains, carries tremendous potential as a way to address issues of poverty and limited healthcare and to foster new technologies needed to improve the sustainability and inclusiveness of growth.” So as I mentioned before, instead of a trade off between growth related policies and equity, the Hanushek’s results are so strong that they suggest that first raising test scores will eventually produce enough extra gain to pay for everything. So this really relieves them of the need to engage in the kinds of debates over priorities that have taken place for as long as education policy has been around.

Now, if that sounds academic, I apologize. Let me try to put it in more concrete terms to make it easier to understand. Sure. So if the United States based on the PISA 2000 scores could have a 20 or 30 year reform plan that would eventually lead them to achieve the level of Finland or Korea’s PISA scores in 2006. Hanushek claims that, Hanushek and Woessmann claims that GDP, United States’ GDP will be 5% bigger. Now Hanushek really spotlights that in 1989, the governors of the United States came together with then president George Bush, and they promised by the year 2000 to make America number one in the world in math and science. So at that time, it would have been a 50 point gain. And so Hanushek argues in a different work but produced by Brookings called “Endangering Prosperity”, that if the US would have stayed the course in 1989, and actually achieve the goals rather than getting distracted, its GDP would be 4.5% greater today. And that would allow us to solve all of our distributional, our, I’m American, apologies our distributional or equity issues that have constantly plagued American education. And even in more concrete terms Hanushek is based on that strong causality. He’s saying that the gains would actually equal and I quote, “20% higher paychecks for the average American worker over the entire 21st century.”

Will Brehm: 22:02

So he’s reading the future with that relationship that he assumes he can read the future and basically says that focus on test scores first and worry about everything else later, because we’re going to increase so much GDP that will be able to pay for everything that education needs. That’s kind of that policy gist.

Jeremy Rappleye: 22:25

That’s absolutely right, Will, and he made this calculation for the United States, as you can imagine, he’s based in the United States. But if you look at the OECD report, in 2015, they actually make the same calculations for all countries worldwide. So we spotlight that in our full paper in the introduction, just picking up the case of Ghana, because OECD really picked up the case of Ghana and say, you would have this huge economic gain if you could just stay the course on raising test scores.

Will Brehm: 22:54

So these are future predictions or projections. Has there ever been like a real life example of like a bit working the way Hanushek and Woessmann theorize?

Jeremy Rappleye: 23:07

Well, I believe that they would probably argue that the piece of data itself shows that it works. So of course, you have up and down fluctuations of individual countries, but I think they would have a hard time showing a particular country or giving you a case of a particular country who enacted reforms and then achieved higher GDP growth. It’s all abstracted to the level of correlation and causality rather than brought back into kind of concrete terms of particular countries.

Will Brehm: 23:44

And your analysis obviously shows that those future projections are incorrect, or wouldn’t necessarily work out the way Hanushek and Woessmann claim. You know, how do we begin to theorize that this connection between test scores and GDP, like what sort of implications does your study have on education policymakers?

Hikaru Komatsu: 24:09

In my opinion, or according to the data, it is okay to say that improving test score both lead to higher economic growth on average, but actually test scores are only one factor as we found, as we said, only 10% of the variation in economic growth was explained by the variation in test scores. So in that sense, educational test scores are only one factor affecting economic growth. And as we see there’s a huge variation in fiscal capital, land or enterprise between countries, and those should affect economic growth. So education is only one of those factors. This is, I think, reasonable understanding of the relationship between economic growth education and then affect us.

Will Brehm: 25:14

So in a sense, we recognize that education plays some role in future economic growth. But there are other things that also affect future economic growth. And we shouldn’t lose sight of them either.

Hikaru Komatsu: 25:25

You’re right. So that problem Professor Hanushek had is that he believed or assumed that it is the sole factor and he uses only test scores to predict future economic growth. But the route is not so simple. This is our point.

Will Brehm: 25:45

And it seems like it’s a simple point you’re making. But like I said, I think it’s quite profound, because it really upsets what countries are pursuing in their educational goals. I mean, it challenges the rise of PISA, I mean, are all of these countries that are trying to join PISA? Is this actually what they should be doing, right? I mean, for me, the policy implications become so much more difficult, and the confidence of certain policy prescriptions kind of goes out the door.

Jeremy Rappleye: 26:16

Yeah, Will. We would wholeheartedly agree with that summary of kind of the implications of our study, it is a simple idea. And it’s pretty obvious even to, let’s say, masters level students, that education is not that complex. But one of the problems is all of this big data creates all the potential for kind of this dog fight using data up at the higher stratosphere. And people can’t really touch that. So as long as you are up there fighting it out, then it seems to be pretty solid. And I think that to be very honest, actually, neither Hikaro or I really like doing this work that much. Right. To be very honest, we don’t really enjoy this work. We’d rather be thinking about big ideas and complex ideas and doing those types of things.

But the problem is that it blocks the view, the simple views of education block the complexity or the depth of what we should be seeing in these ecologies of education or these types of things. Now, that was a very kind of big picture response. But if we have time, I’d like to talk more specifically about the specific policy recommendations and what are the implications of our studies. So we believe that our research findings have recommendations but these are not really recommendations in the usual sense of identifying a best practice or a magic bullet or as a magical potion that will improve education worldwide. Instead, the implications of our research is what we might call negative policy recommendations. And by that, I mean it helps policymakers realize what they should not do. Specifically, it tells policymakers that they should not be seduced by promises that focusing on raising test scores, and purely test scores in areas such as science technology, math is a surefire policy that will raise GDP growth rates, and it tells them not to believe kind of advisors who would come in and tell them that raising test scores alone will lead to enough GDP, future growth to quote “and the financial and distributional problems of education,” unquote. Now I want to even be more specific about this, more concrete, two points. As most listeners will know, one of the biggest educational policy trends over the last two decades has been PISA. And there are currently plans to extend PISA to low income countries through the PISA for development exercise. I think that by 2030, the OECD and the World Bank plan to have PISA in every country worldwide, despite a whole range of critiques from academics, from practitioners, from just the normal belief that education is more complex than that.

The central rationale for the expansion of PISA testing is that it will lead to higher GDP growth. In effect, countries are being persuaded to sign up to PISA, because of the types of claims that we reviewed throughout this interview. But our research shows that this will not happen. Some of my favorite research in recent years have come from scholars around Paul Morris, at the Institute of Education in London, working with young scholars, Euan Auld, Yun You or Bob Adamson in Hong Kong, showing how PISA tests are really driven much more by a range of private companies such as Pearson, ETS, and so on. And scholars like Stephen Ball, Bob Lingard, and Sam Seller also write some great stuff along these lines. And another important line of research comes from folks like Radhika Gorur who writes about the dangers of standardization and how it might ultimately destroy the diversity necessary for future adaptation and innovation in education. And so again, we hope that our research removes the belief that research that, academic research somehow proves the PISA and GDP linkage, and that’s let’s policymakers see all of these warnings much more clearly. And if you let me quickly go on to the second dimension of really concrete, what’s happening now is that, as many listeners will also know, is that the world is, the world of education, where the development more generally is talking about the post 2015 goals. Basically, what comes after the Millennium Development Goals that we’re going in the 1990s. And in terms of education, the Sustainable Development Goal Four is the one that deals with education, it sets global targets for improving learning by 2030. And one of the disappointing things we have noticed in these discussions is that it seems the discussion seem to be imitating the OECD and World Bank that is, we see UNESCO and other agencies referring explicitly to the Hanushek and Woessmann studies to argue for why PISA-style assessments are the best way to achieve Sustainable Development Goal number four. And so compared to discussions around EFA, in the early 1990s, the discussion around the SDG number four seems to be taking this knowledge capital claim as truth as academic truth.

And we worried that this will put the whole world on a course for implementing PISA-style tests. And, of course, the change in curriculum that comes in its wake. I don’t want to be, you know, kind of, to overstate this too much. But we worried that there’s really no evidence for that and that these will be very costly exercises that will ultimately do very little to improve education. So, again, we hope our study will give policymakers the kind of academic research basis for resisting the advances made by the OECD and World Bank.

Will Brehm: 31:59

Have you experienced any pushback about some of the findings because I mean, obviously, you’re challenging some of the wisdom that’s taken for granted by the World Bank, by the OECD, by private companies, like you said, Pearson and ETS, the Educational Testing Service, which produces a whole bunch of tests. So I mean, one would imagine that your negative recommendations that come out of your findings may ultimately create a pushback from those who interests are being challenged.

Jeremy Rappleye: 32:30

Yeah, I guess we would love to have a pushback, because pushback implies an explicit engagement. Again, our findings are not new, that there’s no link between educational outcomes and GDP growth. These claims are very, this idea is actually very old. But what happens is that with each kind of wave of data that comes out that kind of dog fight that I was talking about, kind of gets it goes from maybe kids throwing rocks at each other from different trees up to hot air balloons up to airplanes up to jet planes, and it just keeps going up. There’s no real engagement with the ground level realities that would refute all of this. So if we were to get pushback, we would welcome it. We would love to see the evidence because our mind is not made up. It’s quite possible. I mean, there are no certainties, and it would be wonderful to see a more elaborate discussion around these ideas. So our results are conclusive. But in the sense of with that data set, it conclusively disproves a particular hypothesis or claim, but they’re not conclusive in the terms of a terminus of learning. There’s always more that we can understand about the relation the complex relationship between society, economics, culture and these types of things. So we would really welcome that as a way to elaborate.

Will Brehm: 34:00

Well, I really hope that you can kind of open up this door for a much deeper engagement to get to some of those big questions that you obviously have in mind, but Hikaro Komatsu and Jeremy Rappleye, thank you so much for joining Fresh Ed. It was really a pleasure to talk today.

Hikaru Komatsu: 34:15

Thanks for having us. I really enjoyed it.

Jeremy Rappleye: 34:18

Thank you very much, Will. Keep up the great work. We all appreciate the hard work you’re doing on behalf of educational researchers and educational practitioners worldwide.

Will Brehm 2:12

Hikaru Komatsu和Jeremy Rappleye,你们好,欢迎做客FreshEd!

Hikaru Komatsu 2:16

感谢你邀请我们!

Jeremy Rappleye 2:18

谢谢你,Will!在我们开始之前,我想告诉你的是,我真的特别喜欢你的节目!从中我学到了很多。感谢你创建这个播客,并每周都源源不断地带来如此高质量的访谈!当然,也感谢你能邀请我们来参加。

Will Brehm 2:30

谢谢夸奖!你们两位最近进行了大量的研究,质疑了关于考试成绩与国内生产总值(GDP)之间关系的一些常见假设。那么一般的研究人员认为考试成绩(学生的知识水平)和GDP(国家的发展水平或价值)之间有什么关系呢?

Jeremy Rappleye 2:59

第一个问题我先来回答吧。可以说最常见的理解是,考试成绩与GDP正相关,即成绩越高,未来的GDP就越高。这是最简单的表述。再具体一点的解释就是,人们在某些与经济增长相关学科的成绩越高,那么将来的GDP就越高。这些学科最有可能是数学和科学,语言在某种程度上也算,尤其是阅读。很多国际性的学习测试,例如国际学生评估项目(PISA),考察的就是学生在这三个学科上的学习情况。同时,我们也可以看出这一常见理解中所蕴含的经济模型。具体而言就是科技进步推动经济发展,即科技创新越多,知识积累越厚,未来的经济增长率越高。

Will Brehm 4:02

有什么证据能证明这种“高分数、高GDP”的关系吗?是否有实证研究的数据支持?

Jeremy Rappleye 4:19

是的,尤其在过去10年左右的时间里,这一观点在某些圈子里得到了很强的实证研究支持。展开来说,很多关于目前这个共识的证据主要都是源自于两位研究者,分别是斯坦福大学的埃里克·哈努谢克(Eric Hanushek)教授和慕尼黑大学的卢德格尔·沃斯曼因(Ludger Woessmann)教授。如果我没记错的话,FreshEd之前有一期节目就请到过哈努谢克教授。话说回来,他们两人研究了1960至2000年间,差不多40年的考试成绩,并与同时期世界范围内的经济发展情况相对照。这里所谓的世界范围是指全球近60个国家,绝大多数是在上述时期参加过国际评估和国际成果测试的高收入国家。更具体地来说,他们结合了两项国际比较测试的数据,即国际教育成就评价协会(IEA)的第二次国际数学研究(SIMS)和国际数学与科学趋势研究(TIMSS),以及经济合作与发展组织(OECD)的PISA;GDP采用的是佩恩表(Penn World Table)的标准数据库,感兴趣的读者可以在我们的论文里找到所有的详细数据。哈努谢克和沃斯曼因研究了考试成绩和GDP增长之间的纵向关系,发现两者有很强的相关性。也就是说,在这60个国家里,谁的测试得分越高,谁的GDP增长就越高。这一点过会儿Komatsu教授会详细讨论,尤其是关于相关性和因果的概念。

我在这里想说的是,这些实证研究都非常有说服力,给“高分数、高GDP”的观点带来了有力的支持。此外,哈努谢克和沃斯曼因的研究还扩展到其他很多方面,时间充裕的话我可以具体谈谈。两人于2015年出版了《国家的知识资本:教育与经济增长》一书,对他们的发现进行了最为全面的阐释。

Will Brehm 6:43

你的意思是不是说,成绩和GDP之间有很强的相关性,但这种相关性究竟是不是因果关系还很难说,是吗?我是说,可能有点需要用更专业的统计学术语来帮助理解了。

Jeremy Rappleye 7:02

你问到点子上了!关联性,或者说相关性,和因果性是不一样的。理解这一点很关键。我想最好是一会儿由Komatsu教授来具体解释。在那之前,我先引用两处哈努谢克和沃斯曼因的原话,他们提到成绩和GDP之间有因果关系,而不仅仅是有相关性。第一处是在概述研究的主要发现时,他们写到:“对于影响的程度,OECD 学生水平测试成绩的一个标准差与GDP的平均年增长率有关,在我们观察到的40年间,这一数字高出了两个百分点。”大家可能也都听到了,他们在这里用的词是“关系到”。但此外的其他地方,他们反复谈论的却是“因果关系”。比如我要引用的第二处,他们写到:“此前我们的研究显示,一个国家的技能(即它的经济资本)与长期增长率之间存在因果关系,因此能够推测教育政策是如何影响国家的预期经济效益。”简单来说就是,只要能提高考试成绩,就能实现GDP增长。也只有因果关系才能得出这么肯定的结论。

Will Brehm 8:38

显然,这种肯定性(的结论)一定对教育政策的制定者产生了很多影响吧!要知道,只要提升PISA或TIMSS的成绩就能带来经济增长,政策制定看起来变得容易多了。

Jeremy Rappleye 8:55

那当然,这一主张的吸引力太大了,随之带来的影响也在扩大。政策制定者过去要处理的是和教育相关的复杂方程式,而这一类研究的出现使得他们现在相信,现在他们相信只要大胆变革、提高成绩,20或30年后就会有大幅的经济增长。下面,我再引用一下哈努谢克和沃斯曼因的原话。此举实属无奈,对此我深表歉意,因为我不希望听众们认为是我在曲解哈努谢克和沃斯曼因的意思。他们在书中展示了实施这种旨在提高成绩的政策所能带来的可观的教育收益和经济收益。原话是这么说的:“对中低收入国家而言,80年后的GDP收益会是当前的13倍,平均提高28%;对中高收入国家而言,GDP也会平均增涨16%。”试想如果你是政策制定者,难道你会甘愿放弃这个机会?因此,这一研究极大地激励了政策制定者们,让他们把更多注意力放到(如何提高)数学、自然科学和认知测试的成绩上。

还有一点我想强调的有意思的地方,也许之后可以展开讨论。可能有人会想这种将教育局限到考试成绩的做法会受到很多阻力。但据哈努谢克和沃斯曼因预测,提高成绩所带来的GDP增长如此之大,足以弥补一切教育损失。所以这并不是二选一的问题,而是一场稳赢的政策与过去那种不确定的、模糊的、复杂的政策之间的较量,答案自然不言而喻。

抱歉说了这么多,我还要强调最后一点,是关于这些学术研究的主张如何进入到政策领域的。有两个组织功不可没,一个是世界银行(World Bank),另一个是OECD。他们牢牢抓住这些研究成果,并向世界各国的政策制定者积极推广。前者聘请了哈努谢克和沃斯曼因,要求他们研究成果运用到低收入国家的政策制定中去。2007年世界银行发表了题为《教育质量在经济增长中的作用》的报告。后者同样也聘请了哈努谢克和沃斯曼因来分享研究成果、讨论政策意义,并于2015年发布了《普及基本技能:国家能获得什么》的报告。在谈完我们的研究之后,如果访谈结束前还有时间的话,可以回过头来再讨论一下这些组织在推动实证研究进入具体政策建议中的重要作用。

Will Brehm 12:13

那你们认为哈努谢克和沃斯曼因对成绩与GDP关系的分析有什么问题吗?

Hikaru Komatsu 12:23

我们发现哈努谢克所用数据的时间有问题,换言之,他采用的(与考试成绩进行对照的)经济增长的时间段是不相匹配的。记录的考试成绩的1960至2000年间的数据,对照所用的经济增长情况也是同一时间段。但这点很奇怪,为什么这么说呢?因为从学生长大成人到成为主要劳动力,需要有至少几十年时间。所以我们认为,给定某一时期的考试成绩,应当与其之后一定时期的经济增长进对比。这就是我们发现的问题所在。

Will Brehm 13:17

比如1960年的考试成绩应该与1970年的经济增长率对应,两者之间需要有一段时间差,是这个意思吗?

Hikaru Komatsu 13:31

是的,没错。

Will Brehm 13:31

那你们的研究是用这种方法进行的吗?这样做有什么发现?

Hikaru Komatsu 13:36

是这样的,说起来也简单,我们同样用了哈努谢克所采用的1960至2000年间的成绩数据,将其与后续一段时间,如1980至2000年,或1990至2010年的经济增长相比较。我们得出的结论是,考试成绩与经济增长的相关性并没有很强,比哈努谢克他们之前发现的弱得多。听众们可以在FreshEd网站上查看这些数据。左边是哈努谢克他们的原图,可以看出,经济增长与考试成绩之间表现出较强的相关性(正相关);而右边是我们整理数据后得出的,两者的相关性却不那么明显。我来稍微解释一下,这里我们用的是1995至2014年间的经济增长数据与1960至2000年间的成绩进行分析,可以看出各国经济增长的变化中,只有10%可以用成绩增长的差异来解释。也就是说,剩下的90%都是由其他因素造成的。因此,哈努谢克之前的研究和政策建议里说考试成绩是影响未来经济增长的唯一因素,这是完全不合理的。

Will Brehm 15:40

你们的研究表明只有10%的GDP变化能用考试成绩的变化来解释,那之前哈努谢克和沃斯曼因研究里得出的比率是?

Hikaru Komatsu 15:53

他们说大概在70%左右。我们也试图用哈努谢克的方法,复制出他们的结果,但得出的比率只有57%。与70%之间的差异应该是由于我们用的数据版本不同。为了延长时间段,我们更新了数据版本。也就是说用的是同一数据库,但版本不一样。

Will Brehm 16:28

50%与70%之间的差距并没有很大,但10%与70%的差距就大到足以质疑之前从数据中得出的结论了。

Hikaru Komatsu 16:42

你说的没错。如果像哈努谢克教授最初认为的那样存在因果关系,那么我们就应该能找出给定时间段的考试成绩与后续时间段的经济增长之间有较强的相关性。但我们却发现相关性并没有很强,这表明原先哈努谢克认为的那种关系并不总是因果关系。这就是我们的观点。

Will Brehm 17:17

很多人都以为教育对经济发展的意义非凡,对他们来说,这个重大发现无异于一道晴天霹雳了!

Jeremy Rappleye 17:31

我还想接着补充一下Komatsu教授刚刚提到的观点。要理解70%这个比率,以及这个强大的相关性对政策制定的影响,还有一点很重要,我之前也提到过,这里再展开一下。我先用比较学术的语言解释,之后再换一个简单点的方式,这样方便听众理解。

主要来说,就像哈努谢克和沃斯曼因所声明的那样,如此强的因果关联意味着你可以先提高考试成绩,这样未来就会有足够多的经济增长,然后你可以将这些增长重新进行分配,投入到国家所需的其他所有教育资源。换而言之,为了实现社会公平和包容性,你可以将这些多余的增长重新分配到医疗福祉中去、实现可持续发展目标等等。所以,这就是我们常说的对于教育的争论,学术界普遍持有两种阵营:教育到底是为经济增长?还是为促进公平?是为包容全民?还是为个人发展?这些一直都是学术领域上争论不休的话题。但是哈努谢克他们基于因果关系提出的主张超越了这些争论,填补了学术上的空缺。据2007年世界银行的报告称,如果将GDP的3.5%用于教育,20或30年后考试成绩以标准差为0.5的速率提高,那么GDP的平均增长率能达到5%。他们的原话是:“这比增长红利总额会超过中小学的全部支出。”也就是说,国家如果致力于提高学生的认知水平和测试成绩,那么所带来的经济增长最终会让国家有足够经费实现所有教育目标。在2015年OECD的报告中,哈努谢克和沃斯曼因又写到:“认知水平提高所带来的经济效益潜力无限,是解决贫困和医疗问题的方法之一,且可以推动科技进步,促进可持续发展,实现全面增长。”就像我刚刚说的,哈努谢克他们的研究结论之所以如此强有力的原因,是因为他们并没有在教育政策应该促进增长还是保证公平性之间进行权衡,而是另辟蹊径地表示,只要先提高成绩就能产生足够多的经济效益,最终为一切买单。这让他们避开了前面提到的那些围绕教育政策优先性的争论。

这听上去可能比较学术,不好意思。为方便理解,我举个具体例子吧。比如美国,哈努谢克和沃斯曼因声称,基于其在2000年PISA测试中的成绩,如果有一个20年或30年的改革计划使其提高到2006年PISA测试中的芬兰或韩国的水平,那么美国的GDP会有5%的增长。哈努谢克和沃斯曼因他们还指出,早在1989年,时任美国总统的乔治·布什(George Bush)和各州州长曾承诺到2000年要让美国学生的数学和科学成绩成为世界第一,在那时候,也就是提高50分。他在由布鲁金斯学会(Brookings Institution)出版的另一本题为《濒危的繁荣》的书中称,如果美国在1989年坚持这一政策,切实实现目标而没有分心的话,那么美国的GDP应该比现在多4.5%。那么,这样就能解决所有困扰我们教育系统的分配和公平的问题。抱歉,因为我是美国人,所以用“我们”一词。基于那种超强的因果关系,哈努谢克通过具体的数据表示,(成绩提高)带来的效益会使“在整个21世纪,美国工人的平均收入提高20%。”

Will Brehm 22:02

所以他是在预测未来。基于他认为的因果关系,他主张先将重点放在提高考试成绩上,然后再考虑其他事,因为这样带来的GDP增长会为一切教育需求买单。这是他的主要政策观点,对吗?

Jeremy Rappleye 22:25

完全正确!因为哈努谢克在美国,所以他拿美国做了计算。但如果读一下OECD在2015年的报告,你会发现他们用同样的方法计算了全球的其他国家。你可以在我们发表的完整的论文里看到,在引言部分我们指出了这点,并以加纳为例,因为OECD特别强调说,如果加纳能坚持提高考试成绩的政策,就会为他们带去巨大的经济收益。

Will Brehm 22:54

这些都只是对未来的预测或猜想。那是否有真实的案例来证实哈努谢克和沃斯曼因的理论呢?

Jeremy Rappleye 23:07

关于这点,我相信哈努谢克和沃斯曼因可能会说数据本身就是理论有效的证明。当然,每个国家在发展过程中都会有上下波动,但我认为他们很难给出一个特定国家的实例,来证明说在实行(提高成绩的)教育改革后国家的GDP确实增长了。一切都抽象成关联和因果关系,而不是某个国家的具体情况。

Will Brehm 23:44

而你们的分析明确表示了这些对未来的预测是不正确的,或者说未必像哈努谢克和沃斯曼因声称的那样有效。那么,我们该如何认识考试成绩和GDP之间的联系呢?你们的研究会对教育政策制定者产生什么影响?

Hikaru Komatsu 24:09

在我看来,通过这些数据的分析结果,确实可以说可以这么说,考试成绩的提高都能带来更高的经济增长。但是,成绩实际上只是众多因素中的一个。就像我们之前提到的,只有10%的GDP变化能用成绩的变化来解释。我们可以看到各国的财政、资本、土地或企业之间存在巨大的差异,这些都会影响经济增长。所以教育仅仅是影响因素之一。我认为,这是对经济增长和教育之间关系比较合理的解释。

Will Brehm 25:14

也就是说,我们承认教育对经济增长起到一定作用,但是有其他因素同样影响到未来经济增长,我们不应该顾此失彼,对吗?

Hikaru Komatsu 25:25

没错。哈努谢克的问题在于他认为或者假设教育是唯一因素,并且仅用考试成绩这一项因子来预测未来经济增长。事实上远没有这么简单,这是我们的观点。

Will Brehm 25:45

看起来你们提出了一个很简单的观点,但我认为它非常深刻,因为这项结果着实颠覆了国家在教育目标上的追求。也就是说,你们的观点挑战了PISA的崛起。所有这些国家正在试图加入PISA对吗?这正是众望所归的,不是吗?在我看来,你们在研究中所指出的复杂性会使政策制定变得更难,而依靠特定政策来解决问题的信心也会大打折扣。

Jeremy Rappleye 26:16

没错,完全同意你对我们研究影响的概括,我们确实只提出了一个简单的观点。甚至是硕士阶段的学生都会发现原来教育并不是那么深奥。但其中的问题是,所有这些大数据把事情上升到更高层面,造成了潜在争斗,让人们无法触及。所以只要是身在其中的人都会发现其相当坚不可破。说实话,我和Komatsu教授都不太喜欢做这种研究。相比之下,我们更想讨论一些更深刻、更复杂的想法,做那类的研究。

但问题是,这些所谓简单的教育观点阻碍了其复杂性和深刻性,而这些恰恰是我我们应该在教育生态圈里所看到的。这是一个非常宏观的角度。如果有时间,我想更详细地谈谈具体的政策建议,以及我们研究的影响。我们的研究发现既算得上是建议,又算不上真正的建议。因为我们并没有提出一种解决问题的最优解、一种能改善全球教育的魔法解药。恰恰相反,我们的研究提供了一种我们所称的消极政策建议,这可以帮助政策制定者意识到他们不应该做什么。具体而言,我们告诉政策制定者不要轻易相信,只要提高学业成绩,尤其是那种数学、科学类科目的纯分数就肯定能促进GDP增长这样的承诺,不要轻易相信那些来他们国家声称单凭提高成绩就能带来足够经济增长、“解决教育中的资金和分配问题”的那些咨询顾问。

我再具体谈谈两点。首先第一点,听众们可能也都知道,PISA是过去20年里最受欢迎的教育政策之一,且正在计划拓展到更多低收入国家,通过PISA来促进他们发展。OECD和世界银行计划到2030年将PISA推广至世界上每个国家,尽管对此学界和从业人员都有很多批判的声音,他们普遍认为教育远比其复杂得多。PISA测试得以推广的最主要原因就是它将带来更高的GDP增长。实际上,正是由于我们刚才在整个讨论中所回顾过的那种观点,这些国家才会被劝服加入PISA。

然而,我们的研究恰恰表明那一观点所期待的结果未必会发生。近年来也有其他一些我很喜欢的研究,比如伦敦大学学院教育学院的莫礼时(Paul Morris),他和尤安·奥尔德(Euan Auld)、游韵,以及香港的鲍勃·亚当森(Bob Adamson)等中、青年学者的研究认为,PISA其实更多是由培生(Pearson)、美国教育考试服务中心(ETS)等私企所推动的;史蒂芬·鲍尔(Stephen Ball)、鲍勃·林嘉德(Bob Lingard)和山姆·塞勒(Sam Sellar)等学者在诸多论文里也提出了类似的观点。此外,还有一些学者如拉迪卡·哥尔(Radhika Gorur),他们的研究显示出标准化的危害,以及它将如何最终破坏未来教育变革和创新所需的多样性。这些学术研究都表明PISA和GDP之间并无多少联系。希望我们的研究能再次证明这一点,并帮助政策制定者更清楚地看到学界的这些示警。

我要具体说的第二点,也是听众们所熟知的。2015年提出的可持续发展目标(SGD)是当今世界上最热门的议题,这是继上世纪90年代的千年发展目标后又一项重要的发展议程。教育领域也是如此,SDG中的目标4就着重强调了教育问题,制定了截止2030年的全球性目标,以实现学习水平的提升。但令人失望的是我们注意到目标4似乎是在仿照OECD和世界银行的主张,联合国教科文组织(UNESCO)等其他机构也都明确提到哈努谢克和沃斯曼因的研究,鼓吹PISA之类的评估测试是实现SDG目标4的最佳途径。相比90年代的全民教育(EFA),现在围绕SDG目标4的讨论似乎把这种知识资本的主张奉若真理。我们担心这会使全世界都走上推行PISA式测试的道路,以及由此而来的课程改革等。我不想过分夸大这一点,但我们担心的是,这些举动并无多少证据根基,且花费巨大,最终可能对改善教育并无裨益。因此,希望我们的研究能为政策制定者提供一种学术研究基础,来遏制OECD和世界银行在这方面的发展势头。

Will Brehm 31:59

你们的发现有受到过什么抵触吗?我是说很明显你们质疑了很多组织机构所习以为常的观点,比如世界银行、OECD,还有你提到的培生(Pearson)和负责各种测试的ETS等。他们利益遭到挑战的话,会对你们研究所表明的消极政策进行回击吗?

Jeremy Rappleye 32:30

如果有的话,我们是非常欢迎的,毕竟有回击意味着积极的互动。还是那句话,我们对教育成果与GDP增长之间并无关系的发现并不新鲜,这个观点可以说是非常陈旧的了。但就像我之前提到的那样,随着一波波数据的出现,观点的碰撞就随之升级。最开始可能只是小孩子在不同树上互相扔石头,然后到热气球上,接着到飞机上,最后都到航天器上了。争斗被不断拔高,但在落地环节、现实层面,一直没有太多证据参与到反驳中来。所以我们非常欢迎能有回击、能看到相关证据。我们的观点也不是空穴来风,很有可能就是真的。当然万事没有定论,所以能有更多细致地讨论是非常好的一件事。虽然我们从数据中得出的结论否定了之前的假设,但是学无止境,尤其是社会、经济、文化等之间的复杂关系还需要更多的理解。所以很期待能受到回击,这样能更好地解释我们的主张。

Will Brehm 34:00

我真的希望你们能打开这扇门,探触到你们脑海中已经形成的那些更深刻更复杂的问题。Hikaru Komatsu和Jeremy Rappleye,很高兴你们能来做客FreshEd,再次感谢你们的分享!

Hikaru Komatsu 34:15

感谢邀请,和你交流非常愉快!

Jeremy Rappleye 34:18

谢谢你,Will!感谢你为全世界的教育研究者和从业者做出的努力!继续加油!

Want to help translate this show? Please contact info@freshedpodcast.com

Will Brehm: 2:12

HikaruKomatsu et Jeremy Rappleye, bienvenue à FreshEd.

Hikaru Komatsu: 2:16

Merci de nous recevoir.

Jeremy Rappleye: 2:18

Merci, Will. Avant de commencer, laissez-moi vous dire à quel point j’apprécie votre spectacle. Et j’ai tellement appris de lui. Et je vous félicite vraiment d’avoir créé cet espace et de faire des spectacles de si grande envergure, semaine après semaine. Merci beaucoup de nous recevoir.

Will Brehm: 2:30

Merci pour ces aimables propos. Vous avez beaucoup travaillé ces derniers temps pour réfuter certaines hypothèses banales entre les résultats des tests et le PIB – produit intérieur brut. Quelle est la relation normale que de nombreux chercheurs entretiennent entre les résultats des tests ? Que savent les étudiants et le produit intérieur brut ? Quelle est la croissance d’un pays ou quelle est sa valeur ?

Jeremy Rappleye: 2:59

Oui, merci, Will. Je répondrai à la première question ici, je dirais que la compréhension commune de la relation entre les résultats des tests et le projet intérieur brut est que plus vos résultats aux tests sont élevés, plus votre PIB futur est important. C’est l’affirmation la plus simple qui soit et si nous essayons d’être plus précis, il est entendu que plus les gens obtiennent des résultats aux tests dans une population particulière dans des domaines qui sont, disons, pertinents pour la croissance économique, plus le PIB sera élevé à l’avenir. Ainsi, les domaines pertinents ici sont plus susceptibles d’être définis comme les mathématiques et les sciences ou les scores en mathématiques et en sciences, ainsi que la langue dans une certaine mesure, en particulier la lecture. Les domaines exacts que les évaluations internationales de l’apprentissage telles que PISA mesurent, et dans ce sens, nous pouvons également être plus précis sur le type de modèle économique qui s’inscrit dans cette compréhension commune. Plus précisément, il s’agit d’un modèle qui envisage une économie en croissance grâce au progrès technologique. En d’autres termes, plus l’innovation technologique et l’accumulation de connaissances seront nombreuses, plus les taux de croissance économique seront élevés à l’avenir.

Will Brehm: 4:02

Et quel type de preuve existe-t-il, comme les chercheurs disposent-ils de données, de données empiriques qui montrent que cette relation est correcte, que des résultats plus élevés aux tests seront synonymes d’un PIB plus élevé à l’avenir ?

Jeremy Rappleye: 4:19

Oui. Donc, au cours des dix dernières années, par exemple, la base de recherche empirique pour ces affirmations est devenue très forte dans certains milieux. Maintenant, tentez d’être précis, les preuves de cette compréhension commune sous sa forme actuelle, je crois, proviennent principalement de deux chercheurs : l’un est Eric Hanushek de l’université de Stanford et l’autre Ludger Woessmann. Je m’excuse, je ne prononce probablement pas correctement le nom, basé à l’université de Munich. Et je pense qu’Eric Hanushek est apparu sur FreshEd tout récemment, si je ne me trompe pas. Quoi qu’il en soit, leur travail retrace environ 40 ans d’histoire des résultats aux tests, ce qui correspond à 40 ans de croissance économique mondiale. Donc à peu près des années 1960 à l’an 2000. Et lorsqu’ils disent mondial, ils font en fait référence à environ 60 pays dans le monde, principalement les pays à revenu élevé qui ont participé à des évaluations internationales, des tests de performance internationaux de façon constante au cours de cette période. Pour être plus précis, l’historique des résultats de ces tests sur 40 ans regroupe des données provenant de deux tests comparatifs internationaux : les études IEA-SIMS et TIMSS et les récentes études PISA de l’OCDE. Ainsi, pour le PIB, ils utilisent un ensemble de données standard de la Penn World Table et les auditeurs intéressés peuvent trouver des détails complets à ce sujet dans notre document. Mais je pense que le point ici est que lorsque Hanushek et Woessmann examinent la relation longitudinale entre les résultats des tests et la croissance du PIB, ils trouvent une très forte corrélation. Cela signifie que dans 60 pays, plus les résultats aux tests sont élevés, plus la croissance du PIB est élevée, et je pense que Hikarumight en parle plus en détail, la différence, en particulier entre l’idée d’association et de causalité.

Mais ce que je veux dire ici, c’est que ces affirmations empiriques sont si fortes, qu’elles ont donné beaucoup d’élan à l’idée qu’il existe cette base empirique solide pour le lien entre les résultats des tests et le PIB. Et je pense que le travail de Hanushek et de Woessmann est bien expliqué à de nombreux endroits, comme je l’expliquerai peut-être plus tard dans l’interview. Mais le traitement le plus exhaustif se trouve dans un livre intitulé “The Knowledge Capital of Nations – Education and the Economics of Growth”, qui a été publié en 2015.

Will Brehm: 6:43

Vous avez donc indiqué qu’il y a une forte corrélation, mais est-ce que la relation entre les résultats des tests et le PIB est causale ? Et je veux dire, peut-être que c’est un peu entrer dans le langage statistique plus technique qui pourrait être utile ici, pour essayer de comprendre cette affirmation.

Jeremy Rappleye: 7:02

Oui, c’est donc un point très pertinent. Et il est essentiel de comprendre la différence entre une association ou une corrélation et une causalité, je trouve que nous sommes probablement mieux placés pour attendre la discussion d’Hikaro à ce sujet. Mais laissez-moi vous guider en vous donnant deux citations où Hanushek et Woessmann affirment que la relation est causale, et pas seulement la corrélation. La première citation, qui est en quelque sorte une synthèse des résultats de leurs travaux, dit, je cite, “en ce qui concerne l’ampleur, un écart-type des résultats aux tests mesurés au niveau des étudiants de l’OCDE est associé à un taux de croissance annuel moyen du PIB par habitant, supérieur de deux points de pourcentage sur les 40 ans que nous avons observés”. Maintenant, dans cette citation, ils utilisent le mot association, comme beaucoup d’auditeurs l’auront entendu. Mais ailleurs, ils parlent et évoquent sans cesse la causalité. Voici donc la deuxième citation, ils disent : “nos recherches antérieures démontrent la relation de causalité entre les compétences d’une nation son capital économique, et son taux de croissance à long terme, ce qui permet d’estimer comment les politiques d’éducation affectent la performance économique attendue de chaque nation”. Donc, pour faire simple, si vous pouvez améliorer les résultats aux tests, vous obtiendrez une croissance du PIB plus élevée. Et cette certitude découle de l’idée que la relation est effectivement causale.

Will Brehm: 8:38

Ce niveau de certitude doit évidemment avoir un impact sur les décideurs politiques en matière d’éducation, qui ont le droit de savoir que si vous augmentez les scores mesurés par PISA ou TIMSS, vous obtiendrez une plus grande croissance économique. Il semble que cela facilite grandement la vie des décideurs politiques.

Jeremy Rappleye: 8:55

Tout à fait Will, nous pensons que l’attrait, à la fois l’attrait de cette revendication, et l’impact de cette revendication sont en croissance. Et grâce à ce type d’études, les décideurs politiques qui devaient auparavant faire face à une équation très complexe autour de l’éducation sont amenés à croire que les données révèlent qu’une politique de réforme dynamique qui accroît les résultats aux tests conduira, disons, dans 20 ou 30 ans, à des gains économiques importants, assez importants. Et si je peux vous donner juste une autre citation, et je m’excuse pour les citations, je ne veux pas que vous pensiez que j’ai mal formulé ou résumé le travail d’Eric Hanushek et de Woessmann, mais cette citation, celle de leur auteur, illustre le type de bénéfices spectaculaires en matière d’éducation ou de gains économiques que les politiques peuvent espérer obtenir si elles mettent en œuvre ce type de politiques visant à augmenter les résultats aux tests. Ainsi, je cite : “Pour les pays à revenu moyen inférieur, les gains futurs seraient de 13 fois le PIB actuel et une moyenne de 28 % de PIB plus élevée au cours des 80 prochaines années. Et pour les pays à revenu moyen supérieur, la moyenne serait de 16 % de PIB en plus”. Alors maintenant, Will, si vous êtes un décideur politique, vous ne voudriez pas renoncer à ces jeux, n’est-ce pas ? Cette recherche devient donc une véritable motivation pour les décideurs politiques, qui mettent davantage l’accent non seulement sur les mathématiques et les sciences, mais aussi sur les résultats des tests cognitifs dans tous les domaines.

Mais il existe une partie fascinante que je veux souligner et que nous voulons peut-être décortiquer plus tard dans l’interview. Mais on peut s’attendre à ce que ce genre de rétrécissement du champ de l’éducation autour des résultats des tests suscite beaucoup de réticences. Mais en réalité, les gains de PIB résultant de l’augmentation des résultats aux tests, que Hanushek et Woessmann projettent, sont si importants qu’ils devraient permettre de financer tout ce qui concerne l’éducation. Il ne s’agit donc pas vraiment de choisir entre plusieurs alternatives. Mais au lieu d’une politique gagnante à coup sûr contre une politique plus ou moins identique, l’incertitude, l’ambiguïté, la complexité que nous avons vues par le passé.

Et je suis désolé, c’est une longue réponse, Will. Mais je tiens à insister sur le fait que si nous évoquons la manière dont ces affirmations de la recherche universitaire se frayent un chemin jusqu’à la politique ou ont un impact sur la politique, nous devons parler de deux organisations qui se sont vraiment appropriées ces points de vue et les défendent avec force auprès des décideurs politiques du monde entier. La première est la Banque mondiale, qui a recruté Hanushek et Woessmann pour faire le lien entre les résultats de leurs recherches universitaires et l’élaboration de politiques pour les pays à faible revenu. Et ce rapport a été publié par la Banque mondiale sous le titre “Qualité de l’éducation et croissance économique” en 2007. La deuxième organisation qui a vraiment été à l’avant-garde dans ce domaine est l’OCDE, qui a également engagé Hanushek et Woessmann pour partager leurs conclusions et discuter des implications politiques. Et ce rapport était intitulé ” Universal Basic Skills : What Countries Stand to Gain”, qui a été publié en 2015. Donc, peut-être que vers la fin de l’entretien, après avoir discuté de notre étude, nous pourrons revenir sur la façon dont ces organisations sont réellement au centre de la transformation de ce travail empirique en recommandations politiques concrètes.

Will Brehm: 12:13

Quels sont donc les types de problèmes que vous trouvez dans l’analyse de Hanushek et Woessmann sur la relation entre les résultats des tests et le PIB ?

Hikaru Komatsu: 12:23

D’accord, le problème rencontré est le déphasage temporel, c’est-à-dire que le professeur Hanushek a utilisé une période inappropriée pour la croissance économique. C’est-à-dire que le professeur Hanushek compare les résultats des tests enregistrés entre 1960 et 2000 avec la croissance économique pour la même période. Mais c’est un peu étrange. Pourquoi, parce qu’il faut au moins plusieurs décennies pour que les étudiants deviennent adultes et occupent une grande partie de la population active. Donc, de notre point de vue, les résultats des tests pour une période donnée devraient être comparés à la croissance économique des périodes suivantes. C’est le problème que nous avons rencontré.

Will Brehm: 13:17

Ainsi, par exemple, les résultats des tests de 1960 devraient être liés au taux de croissance économique, par exemple, dans les années 1970, il doit y avoir une sorte d’écart entre les deux, est-ce exact ?

Hikaru Komatsu: 13:31

C’est tout à fait exact.

Will Brehm: 13:31

D’accord. Alors, dans votre étude, je veux dire, avez-vous fait cela et qu’avez-vous trouvé ?

Hikaru Komatsu: 13:36

Nous l’avons réalisé, notre étude est très simple. Nous comparons les résultats des tests de 1960 à 2000, ce qui correspond exactement aux données utilisées par le professeur Hanushek. Nous mettons ces données en parallèle avec la croissance économique des périodes suivantes, comme 1980 à 2000 ou 1990 à 2010, ou quelque chose comme ça. Et nous avons trouvé que la relation entre les résultats des tests et la croissance économique était beaucoup plus faible que celle rapportée par le professeur Hanushek. Le public verrait probablement un chiffre sur le web, sur le site de FreshEd, et il y aurait deux chiffres, celui de gauche est le chiffre original rapporté par le professeur Hanushek. Et il existe une relation étroite entre la croissance économique et les résultats aux tests. Alors que le chiffre de droite est celui que nous avons trouvé et la relation est très peu claire. Permettez-moi donc d’expliquer comment nous avons établi cette relation lorsque les résultats des tests de 1960 à 2000 ont été comparés à la croissance économique. Pour les années 1995 à 2014, seuls 10 % des variations de la croissance économique entre les pays s’expliquent par la variation des résultats aux tests. Autrement dit, les 90 % restants de la variation de la croissance économique devraient être responsables d’autres facteurs. Cela revient à dire qu’il est totalement déraisonnable d’utiliser les résultats des tests comme seul facteur pour prédire la croissance économique future. Et c’est ce que le professeur Hanushek a fait dans son étude et ses recommandations politiques.

Will Brehm: 15:40

Ainsi, dans votre étude, vous avez constaté que 10 % de la variation du PIB peut s’expliquer par la variation des résultats aux tests. Quel pourcentage l’étude de Hanushek et Woessmann a-t-elle mis en évidence ?

Hikaru Komatsu: 15:53

Leur pourcentage était sans doute d’environ 70 et nous essayons de reproduire la conclusion du professeur Hanushek, dans notre cas, le pourcentage était d’environ 57 et la différence entre 57, 70 serait due à la différence de version des données que nous avons utilisées. Afin de prolonger cette période, nous avons utilisé une version actualisée de ces données, cet ensemble de données est exactement le même, mais la différence n’est que la version.

Will Brehm: 16:28

Une différence entre 50 et 70 % est plutôt minime. Mais la différence entre 10 % et 70 % est suffisante pour remettre en question les conclusions fondamentales qui sont tirées de ces données.

Hikaru Komatsu: 16:42

Oui, en effet. Si cette relation décrite à l’origine par le professeur Hanushek est causale, nous aurions dû trouver cette relation relativement forte entre les résultats des tests pour une période donnée et la croissance économique pour les périodes suivantes. Mais nous avons trouvé une relation très faible, ce qui suggère que la relation rapportée à l’origine par le professeur Hanushek ne représente pas toujours la relation de cause à effet. C’est là où nous voulons en venir.

Will Brehm: 17:17

Il semble que ce soit un point très fondamental qui pourrait être plutôt déconcertant pour les hypothèses de nombreuses personnes sur l’éducation et sa valeur pour la croissance économique.

Jeremy Rappleye: 17:31

Merci, Will, j’aimerais revenir un peu sur ce que Komatsu sensei a évoqué là-bas. Un des points majeurs à comprendre à propos de ces 70 % de variation est expliqué par les résultats des tests, la puissance de cette corrélation conduit à des recommandations politiques très fortes. Donc, je vais essayer de déballer un peu ce que j’ai dit plus tôt, parce que je pense que c’est un point important, je vais essayer de le faire de manière académique d’abord, et ensuite je vais essayer de donner une version simple qui sera beaucoup plus facile à comprendre pour les auditeurs.

Mais fondamentalement, si vous avez un lien de causalité de corrélation aussi fort, alors Hanushek et Woessmann affirment que vous pouvez d’abord accroître vos résultats aux tests, et cela produira une croissance tellement excessive à l’avenir, que vous pouvez réorienter cette croissance excessive vers tous les autres types de biens éducatifs dont vous avez besoin. Ainsi, en termes d’équité, en termes d’inclusion, vous pourriez même réorienter cette somme supplémentaire vers les soins de santé, vers des objectifs de durabilité, toutes ces choses. Comme nous le savons tous les deux, il s’agit là de deux aspects du camp : l’éducation pour la croissance économique, ou bien les actions, l’inclusion, le développement personnel. Ce sont les types de débats qui ont toujours été menés avec l’éducation en tant qu’étude académique, mais il est capable de transcender, ils sont capables de transcender ce débat basé sur les fortes revendications causales, cependant, juste pour remplir cela de manière académique. L’affirmation veut donc que si 3,5 % du PIB est dépensé pour l’éducation, cela provient du rapport de la Banque mondiale de 2007. Mais si, sur 20 ou 30 ans, vous pouviez accroître vos résultats aux tests de cinq points d’écart type, cela entraînerait une hausse de 5 % du PIB en moyenne, et je cite : “ce dividende brut couvrirait largement toutes les dépenses en matière d’écoles primaires et secondaires”. Cela revient à dire que si vous vous concentrez sur l’accroissement des niveaux cognitifs, des résultats aux tests, vous pourriez obtenir une croissance suffisante pour obtenir en fin de compte plus d’argent pour l’éducation, quel que soit le type d’objectifs éducatifs que vous souhaitez poursuivre. Dans le rapport de l’OCDE de 2015, Hanushek et Woessmann écrivent que “les avantages économiques des gains cognitifs offrent un potentiel énorme pour résoudre les problèmes de pauvreté et de soins de santé limités et pour encourager les nouvelles technologies nécessaires pour améliorer la durabilité et l’intégration de la croissance”. Ainsi, comme je l’ai déjà mentionné, au lieu d’un compromis entre les politiques liées à la croissance et l’équité, les résultats du Hanushek sont si probants qu’ils suggèrent qu’une première hausse des résultats aux tests produira finalement suffisamment de gains supplémentaires pour tout payer. Cela les dispense donc vraiment de s’engager dans le genre de débats sur les priorités qui ont lieu depuis que la politique de l’éducation existe.

Maintenant, si cela paraît académique, je m’en excuse. Laissez-moi essayer de le formuler en termes plus concrets pour le rendre plus facile à comprendre. Bien sûr, si les États-Unis se fondaient sur les résultats de PISA 2000, ils pourraient avoir un plan de réforme sur 20 ou 30 ans qui les amènerait à atteindre le niveau des résultats de PISA de la Finlande ou de la Corée en 2006. Hanushek et Woessmann affirment que le PIB, le PIB des États-Unis sera supérieur à 5 %. Hanushek met en avant le fait qu’en 1989, les gouverneurs des États-Unis se sont réunis avec le président George Bush et qu’ils ont promis de faire de l’Amérique le numéro un mondial en mathématiques et en sciences d’ici l’an 2000. À l’époque, cela aurait donc représenté un gain de 50 points. C’est pourquoi Hanushek affirme dans un autre ouvrage, mais produit par Brookings et intitulé “Endangering Prosperity”, que si les États-Unis avaient maintenu le cap en 1989 et avaient réellement atteint les objectifs fixés plutôt que de se laisser distraire, leur PIB serait aujourd’hui supérieur de 4,5 %. Et cela nous permettrait de résoudre tous nos problèmes de distribution, de, je suis américain, d’excuses, de répartition ou d’équité qui ont constamment affligé l’éducation américaine. Et même en termes plus concrets, Hanushek est basé sur cette forte causalité. Il dit que les gains seraient en fait égaux et je cite : “20% de salaires en plus pour le travailleur américain moyen sur l’ensemble du 21ème siècle”.

Will Brehm: 22:02

Ainsi, il lit l’avenir avec cette relation qu’il suppose pouvoir lire l’avenir et dit en gros qu’il faut se focaliser sur les résultats des tests d’abord et se préoccuper de tout le reste ensuite, parce que nous allons tellement augmenter le PIB que nous pourrons payer tout ce dont l’éducation a besoin. C’est en quelque sorte l’essence même de cette politique.

Jeremy Rappleye: 22:25

C’est bien cela, Will, et il a fait ce calcul pour les États-Unis, comme vous pouvez l’imaginer, il est basé aux États-Unis. Mais si vous regardez le rapport de l’OCDE, en 2015, ils font en fait les mêmes calculs pour tous les pays du monde. C’est pourquoi nous mettons l’accent sur ce point dans notre document intégral en introduction, en reprenant le cas du Ghana, parce que l’OCDE a vraiment repris le cas du Ghana et a dit : “Vous auriez cet énorme gain économique si vous pouviez simplement maintenir le cap sur l’amélioration des résultats aux tests.

Will Brehm: 22:54

Il s’agit donc de prévisions ou de projections futures. Y a-t-il jamais eu un exemple concret de la façon dont Hanushek et Woessmann théorisent ?

Jeremy Rappleye: 23:07

Eh bien, je suppose qu’ils pourraient probablement soutenir que l’élément de données lui-même montre que cela fonctionne. Il existe donc bien évidemment des variations à la hausse et à la baisse pour chaque pays, mais je pense qu’il serait difficile de montrer un pays en particulier ou de vous donner le cas d’un pays qui a mis en œuvre des réformes et qui a ensuite enregistré une croissance plus élevée de son PIB. Tout est ramené au niveau de la corrélation et de la causalité plutôt qu’aux termes concrets de pays particuliers.

Will Brehm: 23:44

Votre analyse indique évidemment que ces projections sont incorrectes, ou ne fonctionneraient pas nécessairement comme le prétendent Hanushek et Woessmann. Vous savez, comment pouvons-nous commencer à théoriser que ce lien entre les résultats des tests et le PIB, comme par exemple quel type d’implications votre étude a sur les décideurs politiques de l’éducation ?

Hikaru Komatsu: 24:09

À mon humble avis, ou selon les données, on peut affirmer que l’amélioration des résultats aux tests entraîne une croissance économique plus élevée en moyenne, mais en réalité, les résultats aux tests ne sont qu’un facteur parmi d’autres, car nous avons découvert, comme nous l’avons dit, que seulement 10 % de la variation de la croissance économique s’expliquait par la variation des résultats aux tests. Donc, en ce sens, les résultats des tests éducatifs ne sont qu’un facteur influençant la croissance économique. Et comme nous le voyons, il existe une énorme variation du capital fiscal, des terres ou des entreprises entre les pays, et cela devrait affecter la croissance économique. L’éducation n’est donc qu’un de ces facteurs. C’est, je pense, une compréhension raisonnable de la relation entre la croissance économique, l’éducation et les effets sur nous.

Will Brehm: 25:14

Ainsi, dans un sens, nous reconnaissons que l’éducation joue un rôle dans la croissance économique future. Mais il existe d’autres facteurs qui influent également sur la croissance économique future. Et nous ne devrions pas les perdre de vue non plus.

Hikaru Komatsu: 25:25

Vous avez raison. Le problème du professeur Hanushek est donc qu’il croit ou suppose que c’est le seul facteur et qu’il n’utilise que les résultats des tests pour prédire la croissance économique future. Mais le chemin n’est pas si simple. C’est là où nous voulons en venir.

Will Brehm: 25:45

Et on dirait que c’est un simple point de vue. Mais comme je l’ai dit, je pense que c’est assez sérieux, parce que cela bouleverse vraiment les objectifs éducatifs des pays. Je veux dire que cela remet en question la montée en puissance du PISA, je veux dire, est-ce que tous ces pays qui essaient de rejoindre le PISA ? Est-ce vraiment ce qu’ils devraient faire, n’est-ce pas ? Je veux dire que pour moi, les implications politiques deviennent beaucoup plus difficiles, et la confiance de certaines prescriptions politiques disparaît en quelque sorte.

Jeremy Rappleye: 26:16

En effet, Will. Nous sommes tout à fait d’accord avec ce résumé des implications de notre étude, c’est une idée simple. Et il est assez évident, même pour, disons, des étudiants de niveau master, que l’éducation n’est pas si complexe. Mais l’un des problèmes est que toutes ces grandes données créent un potentiel pour ce genre de combat de chiens en utilisant des données de la haute stratosphère. Et les gens ne peuvent pas vraiment y toucher. Donc, tant que vous êtes là-haut à vous battre, alors cela semble assez solide. Et je pense que pour être très honnête, en fait, ni Hikaruor ni moi n’aimons vraiment faire ce travail à ce point. C’est vrai. Pour être très honnête, nous n’aimons pas vraiment ce travail. Nous préférons penser à de grandes idées et à des idées complexes et faire ce genre de choses.

Mais le problème est que cela limite la vue, les vues simples de l’éducation limitent la complexité ou la profondeur de ce que nous devrions voir dans ces écologies de l’éducation ou ce genre de choses. C’était une sorte de réponse globale. Mais si nous avons le temps, j’aimerais parler plus précisément des recommandations politiques spécifiques et des implications de nos études. Nous pensons donc que les résultats de nos recherches comportent des recommandations, mais il ne s’agit pas vraiment de recommandations au sens habituel du terme, c’est-à-dire l’identification d’une meilleure pratique ou d’une solution miracle ou d’une potion magique qui améliorera l’éducation dans le monde entier. Au contraire, les implications de nos recherches sont ce que l’on pourrait appeler des recommandations politiques négatives. Et par là, je veux dire qu’elles aident les décideurs politiques à réaliser ce qu’ils ne devraient pas faire. Plus précisément, elle leur dit qu’ils ne doivent pas se laisser séduire par des promesses selon lesquelles le fait de se concentrer sur l’augmentation des notes d’examen, et uniquement des notes d’examen dans des domaines tels que la science et la technologie, les mathématiques est une politique infaillible qui augmentera les taux de croissance du PIB, et elle leur dit de ne pas croire le genre de conseillers qui viendraient leur dire que l’augmentation des notes d’examen à elle seule conduira à un PIB suffisant, à une croissance future pour citer “et aux problèmes financiers et de répartition de l’éducation”, pour ne pas citer. Je voudrais maintenant être encore plus précis sur ce point, plus concret, sur deux points. Comme la plupart des auditeurs le savent, l’une des plus grandes tendances en matière de politique de l’éducation au cours des deux dernières décennies a été l’enquête PISA. Et il est actuellement prévu d’étendre le PISA aux pays à faible revenu dans le cadre de l’exercice PISA pour le développement. Je pense que d’ici 2030, l’OCDE et la Banque mondiale prévoient de mettre en place le PISA dans tous les pays du monde, en dépit de toute une série de critiques émanant d’universitaires, de praticiens, de la croyance normale selon laquelle l’éducation est plus complexe que cela.

La principale raison de l’extension du test PISA est qu’elle mènera à une plus forte croissance du PIB. En effet, les pays sont amenés à s’inscrire au PISA, en raison des types d’allégations que nous avons analysées tout au long de cet entretien. Mais nos recherches indiquent que ce ne sera pas le cas. Certaines de mes recherches préférées de ces dernières années ont été menées par des chercheurs autour de Paul Morris, à l’Institut de l’éducation de Londres, en collaboration avec de jeunes universitaires, Euan Auld, Yun You ou Bob Adamson à Hong Kong, ce qui illustre le fait que les tests PISA sont en réalité beaucoup plus pilotés par une série d’entreprises privées telles que Pearson, ETS, etc. Et des universitaires comme Stephen Ball, Bob Lingard et Sam Seller écrivent également de très bons articles dans ce sens. Une autre ligne de recherche importante émane de personnes comme Radhika Gorur qui écrit sur les dangers de la normalisation et sur la manière dont elle pourrait finalement détruire la diversité nécessaire à l’adaptation et à l’innovation futures dans l’éducation. Nous voulons donc, une fois de plus, que nos recherches fassent disparaître la croyance selon laquelle les recherches universitaires prouvent d’une manière ou d’une autre le lien entre le PISA et le PIB, et que les décideurs politiques perçoivent beaucoup plus clairement tous ces avertissements. Et si vous me permettez de passer rapidement à la deuxième dimension du concret, ce qui se passe maintenant, comme beaucoup d’auditeurs le savent aussi, c’est que le monde est, le monde de l’éducation, où le développement parle plus globalement des objectifs de l’après 2015. Fondamentalement, ce qui suit les objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement que nous allons dans les années 1990. Et en matière d’éducation, le quatrième objectif de développement durable est celui qui concerne l’éducation, il fixe des objectifs au niveau mondial pour améliorer l’apprentissage d’ici 2030. Et l’une des choses regrettables que nous avons remarquées dans ces discussions, c’est qu’il semble que la discussion imite l’OCDE et la Banque mondiale ; c’est-à-dire que nous voyons l’UNESCO et d’autres agences se référer explicitement aux études de Hanushek et Woessmann pour défendre les raisons pour lesquelles les évaluations de type PISA sont le meilleur moyen d’atteindre le quatrième objectif de développement durable. Ainsi, par rapport aux discussions autour de l’EPT, au début des années 1990, la discussion autour du quatrième objectif de développement durable semble prendre cette affirmation de capital de connaissances comme une vérité, une vérité académique.

Et nous nous sommes inquiétés de ce que cela mette le monde entier sur la voie de la mise en œuvre de tests de type PISA. Et, bien sûr, le changement de programme qui s’ensuit. Je ne veux pas, vous savez, un peu trop exagérer. Mais nous craignons qu’il n’y ait pas vraiment de preuves à cet égard et qu’il s’agisse d’exercices très coûteux qui, en fin de compte, ne contribueront que très peu à améliorer l’éducation. Nous espérons donc, une fois encore, que notre étude donnera aux décideurs politiques le type de base de recherche universitaire qui leur permettra de résister aux avancées de l’OCDE et de la Banque mondiale.

Will Brehm: 31:59

Avez-vous fait l’expérience d’un recul par rapport à certaines des conclusions parce que, de toute évidence, vous remettez en question certaines des idées reçues par la Banque mondiale, par l’OCDE, par des entreprises privées, comme vous l’avez dit, par Pearson et par ETS, le Service d’évaluation de l’éducation, qui produit toute une série de tests. On pourrait donc supposer que vos recommandations négatives qui découlent de vos conclusions pourraient finalement créer une réaction de rétraction de la part de ceux dont les intérêts sont contestés.

Jeremy Rappleye: 32:30

Oui, je crois que nous aimerions vivement avoir un retour en arrière, parce que le retour en arrière implique un engagement explicite. Encore une fois, nos observations ne sont pas nouvelles, à savoir qu’il n’y a pas de lien entre les résultats scolaires et la croissance du PIB. Ces affirmations sont très, très anciennes, cette idée est en réalité très ancienne. Mais ce qui se passe, c’est qu’à chaque vague de données qui sortent de ce genre de combat de chiens dont je parlais, cela va des enfants qui se lancent des pierres depuis différents arbres jusqu’aux ballons à air chaud en passant par les avions à réaction, et cela ne cesse de croître. Il n’y a pas de véritable engagement avec les réalités du terrain qui réfuterait tout cela. Donc, si nous obtenions un retour en arrière, nous l’accueillerions avec plaisir. Nous aimerions voir les preuves parce que notre décision n’est pas prise. C’est tout à fait possible. Je veux dire qu’il n’y a pas de certitudes, et il serait merveilleux de voir une discussion plus élaborée autour de ces idées. Nos résultats sont donc concluants. Mais dans le sens où avec cet ensemble de données, ils réfutent de manière concluante une hypothèse ou une affirmation particulière, mais ils ne sont pas concluants en termes de fin d’apprentissage. Nous pouvons toujours en comprendre davantage sur la relation complexe entre la société, l’économie, la culture et ce genre de choses. Nous serions donc très heureux de pouvoir élaborer sur ce point.

Will Brehm: 34:00

J’espère vraiment que vous pourrez ouvrir cette porte à un engagement beaucoup plus profond pour aborder certaines de ces grandes questions que vous avez évidemment à l’esprit, mais HikaruKomatsu et Jeremy Rappleye, merci beaucoup d’avoir rejoint Fresh Ed. C’était vraiment un plaisir de vous parler aujourd’hui.

Hikaru Komatsu: 34:15

Merci de nous recevoir. J’ai vraiment apprécié.

Jeremy Rappleye: 34:18

Merci infiniment, Will. Continuez votre excellent travail. Nous apprécions tous le dur labeur que vous accomplissez au nom des chercheurs en éducation et des praticiens de l’éducation du monde entier.

Translation sponsored by NORRAG.

Want to help translate this show? Please contact info@freshedpodcast.com

Have any useful resources related to this show? Please send them to info@freshedpodcast.com